-Andrew Macken

A few weeks ago, a house was listed for sale in Sydney’s famous Bondi at $3.8 million. (There were no water views, unlike for the $20.1 million penthouse apartment that set the Australian record last week)[1]. The house went to auction, with opening bids at $4 million. It sold for $6.1 million.

In an environment of rock-bottom interest rates, locked in for years to come by central bank policymakers, asset prices are continuing their appreciation. In the case of many Australian property markets, these price movements have been fierce.

We are witnessing a sharp acceleration in inequality. In the US last year, the wealthiest one percent of households increased their wealth by US$4 trillion – equivalent to about 35% of the extra wealth generated nationwide.[2] The bottom 50% of households shared in only four percent of the gains.

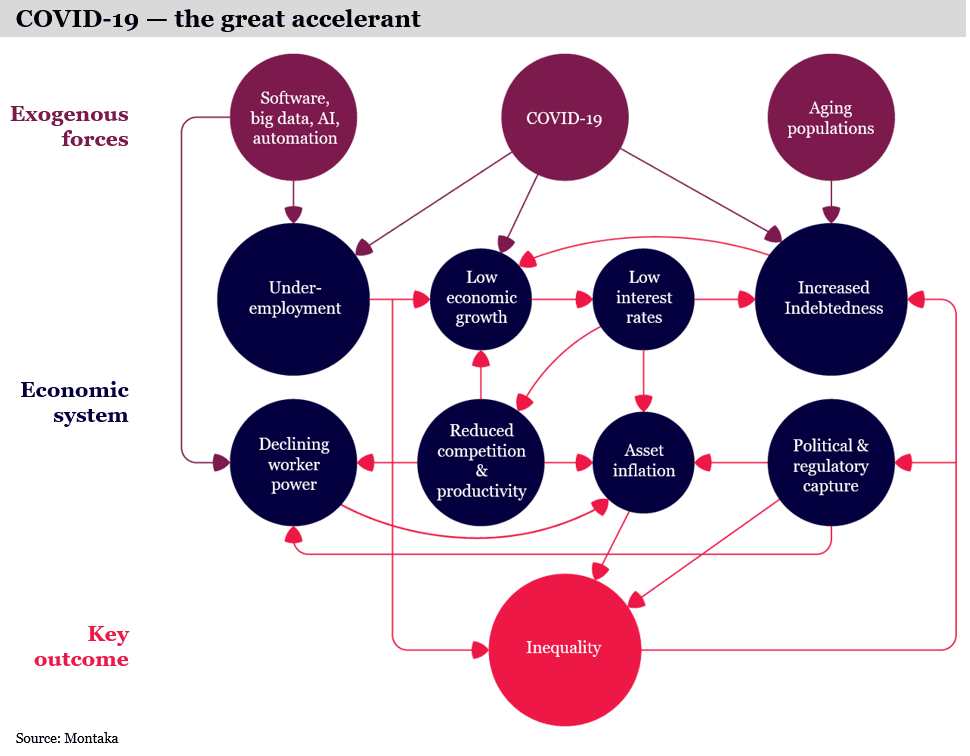

We believe inequality will only become more extreme, with Covid-19 accelerating a number of the dynamics in our economic system that give rise to inequality. And growing inequality will feedback into our economic system in two key ways: more grievances and more debts.

More grievances

When inequality is high, democratic systems face a fundamental question: how can a political system that gives the ballot to all coexist with an economic system that concentrates wealth in the hands of the few?

As well articulated by political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson in their new book, Let Them Eat Tweets:

“Extremely unequal societies have a hard time finding that delicate balance between protecting ordinary citizens and reassuring the privileged few.”[3]

The authors study the historical record to uncover a clear pattern of behaviour by those political parties on the right facing this Conservative Dilemma:

“Whenever economic elites have grossly disproportionate power and come to see their economic interests as opposed to those of ordinary citizens, they are likely to promote social divisions.”

Furthermore, in a recent study of 450 political parties in 41 democracies between 1945 and 2010, it was found that when inequality was higher, parties on the right ramped up their emphasis on divisive noneconomic issues, especially those surrounding race, ethnicity, religion and immigration.[4] This might sound somewhat familiar to observers of the US political environment over the last four years – and particularly in the lead up to the recent 2020 general election.

This is, perhaps, one important reason why large-scale reversals of income inequality within the context of democracies have not happened orderly, historically. Not only do plutocrats fight to retain their power but, in order to do so, tend to resort to outrage-stoking, thereby exacerbating political instability.

More debts

It is easily understood that, while most people spend close to everything they earn on goods and services, the very wealthy do not. If you give a wealthy person one extra dollar, it will most likely be saved (i.e. invested in assets, including property), not spent.

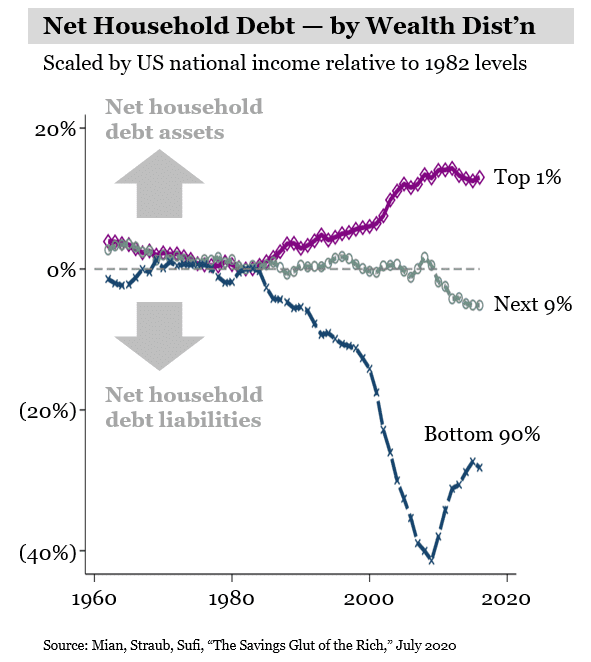

This means the world’s spending is increasingly being supported by consumers in the lowest-wealth cohorts who need to borrow to fund their expenditures. (Perhaps this partially explains the booming buy-now-pay-later space).

In their excellent book Trade Wars are Class Wars, Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis explain that:

“For the world as a whole, rising inequality means the value of those assets is necessarily contingent on continued increases in spending by people who have progressively lower shares of national income. The only way to make this work is rising debt.”

And this is exactly what we have seen in the world’s largest economy, particularly over the last 40 years – the period during which income inequality increased significantly in the US.

Going “long” inequality

For those not holding their breath for a large-scale reversal of these trends any time soon, one interesting way to benefit is to own the world’s leading alternative asset managers. Montaka owns Blackstone, KKR and The Carlyle Group, for example, on the basis that these global trends (like them or not) are driving asset owners to own more assets, at increasing valuations. And these assets are increasingly being managed by the world’s highest-quality and largest-scale investment platforms in return for fee-income streams that are indexed to their value. The result is a sustainably growing profit stream for shareholders. And this, of course, is particularly valuable in a low interest rate environment.

A long-term marshmallow test for capitalism

We observe that the economic system which has evolved and delivered great benefits to so many is at risk of being undermined over the long-term by the very side-effects the system itself creates – particularly inequality.

Ironically, the price of preserving the overarching structure of this economic system is perhaps making it work more beneficially and equitably for the broader population. It perhaps represents the mother of all marshmallow tests for the preservation of capitalism as it was originally intended.

This article is based on a new in-depth Montaka research paper titled Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer at Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

[1] (AFR) Website founder’s huge bid breaks Australian apartment price record, March 2021

[2] (Bloomberg) The Wealth Gains That Made 2020 a Banner Year for the Richest 1%, March 2021

[3] Hacker, Pierson, “Let Them Eat Tweets,” 2020

[4] Tavits, Potter, “The Effect of Inequality and Social Identity on Party Strategies,” 2015

More inequality. More grievances. More debts.

-Andrew Macken

A few weeks ago, a house was listed for sale in Sydney’s famous Bondi at $3.8 million. (There were no water views, unlike for the $20.1 million penthouse apartment that set the Australian record last week)[1]. The house went to auction, with opening bids at $4 million. It sold for $6.1 million.

In an environment of rock-bottom interest rates, locked in for years to come by central bank policymakers, asset prices are continuing their appreciation. In the case of many Australian property markets, these price movements have been fierce.

We are witnessing a sharp acceleration in inequality. In the US last year, the wealthiest one percent of households increased their wealth by US$4 trillion – equivalent to about 35% of the extra wealth generated nationwide.[2] The bottom 50% of households shared in only four percent of the gains.

We believe inequality will only become more extreme, with Covid-19 accelerating a number of the dynamics in our economic system that give rise to inequality. And growing inequality will feedback into our economic system in two key ways: more grievances and more debts.

More grievances

When inequality is high, democratic systems face a fundamental question: how can a political system that gives the ballot to all coexist with an economic system that concentrates wealth in the hands of the few?

As well articulated by political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson in their new book, Let Them Eat Tweets:

The authors study the historical record to uncover a clear pattern of behaviour by those political parties on the right facing this Conservative Dilemma:

Furthermore, in a recent study of 450 political parties in 41 democracies between 1945 and 2010, it was found that when inequality was higher, parties on the right ramped up their emphasis on divisive noneconomic issues, especially those surrounding race, ethnicity, religion and immigration.[4] This might sound somewhat familiar to observers of the US political environment over the last four years – and particularly in the lead up to the recent 2020 general election.

This is, perhaps, one important reason why large-scale reversals of income inequality within the context of democracies have not happened orderly, historically. Not only do plutocrats fight to retain their power but, in order to do so, tend to resort to outrage-stoking, thereby exacerbating political instability.

More debts

It is easily understood that, while most people spend close to everything they earn on goods and services, the very wealthy do not. If you give a wealthy person one extra dollar, it will most likely be saved (i.e. invested in assets, including property), not spent.

This means the world’s spending is increasingly being supported by consumers in the lowest-wealth cohorts who need to borrow to fund their expenditures. (Perhaps this partially explains the booming buy-now-pay-later space).

In their excellent book Trade Wars are Class Wars, Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis explain that:

And this is exactly what we have seen in the world’s largest economy, particularly over the last 40 years – the period during which income inequality increased significantly in the US.

Going “long” inequality

For those not holding their breath for a large-scale reversal of these trends any time soon, one interesting way to benefit is to own the world’s leading alternative asset managers. Montaka owns Blackstone, KKR and The Carlyle Group, for example, on the basis that these global trends (like them or not) are driving asset owners to own more assets, at increasing valuations. And these assets are increasingly being managed by the world’s highest-quality and largest-scale investment platforms in return for fee-income streams that are indexed to their value. The result is a sustainably growing profit stream for shareholders. And this, of course, is particularly valuable in a low interest rate environment.

A long-term marshmallow test for capitalism

We observe that the economic system which has evolved and delivered great benefits to so many is at risk of being undermined over the long-term by the very side-effects the system itself creates – particularly inequality.

Ironically, the price of preserving the overarching structure of this economic system is perhaps making it work more beneficially and equitably for the broader population. It perhaps represents the mother of all marshmallow tests for the preservation of capitalism as it was originally intended.

This article is based on a new in-depth Montaka research paper titled Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer at Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

[1] (AFR) Website founder’s huge bid breaks Australian apartment price record, March 2021

[2] (Bloomberg) The Wealth Gains That Made 2020 a Banner Year for the Richest 1%, March 2021

[3] Hacker, Pierson, “Let Them Eat Tweets,” 2020

[4] Tavits, Potter, “The Effect of Inequality and Social Identity on Party Strategies,” 2015

This content was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.