-Andrew Macken

Most investors are aware that COVID-19 is accelerating economic forces such as indebtedness, low interest rates and asset price inflation. But there is perhaps less awareness of another powerful trend that COVID is also accelerating: the ‘Gilded Age’-style economic inequality that has been emerging in recent decades.

Inequality is an important consequence of our economic system, and we see it becoming more extreme in a post-COVID world.

Growing inequality will lead to slower economic growth, even more indebtedness, increased financial risk, and greater political instability. These are all factors that will have a significant impact on investors’ portfolios.

Inequality creates winners and losers. And there are key steps that investors can take to be on the right side of these changes – to not only protect their portfolios from accelerating inequality, but also generate strong investment returns into the future.

The return of the Gilded Age

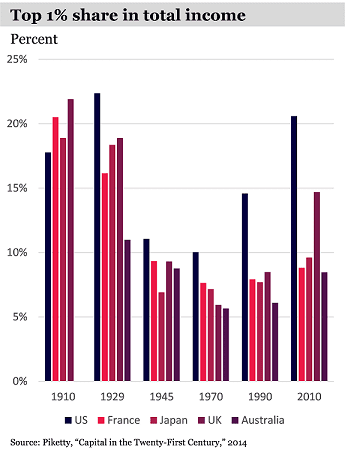

At the start of the 20th Century, the world was in the grip of the ‘Gilded Age’ as described by Mark Twain. Plutocrats accumulated vast fortunes and economic inequality surged as the top 1% captured a disproportionate share of income from wages and capital.

Following two world wars, this inequality reduced dramatically with higher taxes, weak asset prices, and financial repression by governments. That continued for three generations.

But inequality began to return in the 1980s and 1990s, driven by ‘super managers’ – corporate executives earning huge wages and bonuses. And we now have a new era of billionaire plutocrats such as Gates, Bezos and Musk. Indeed, some historians are calling our current economic situation the ‘New Gilded Age’.

The US has found itself back to pre-WWII levels of inequality. The top 1 per cent capture more than 20 per cent of total income, up from 10 per cent just 40 years ago. What’s more, that doubling of income flowing to the top 1 per cent came from the bottom 50 per cent. More recent data from the US Federal Reserve suggests that over 30 per cent of total wealth is attributable to the top 1 per cent in the US.

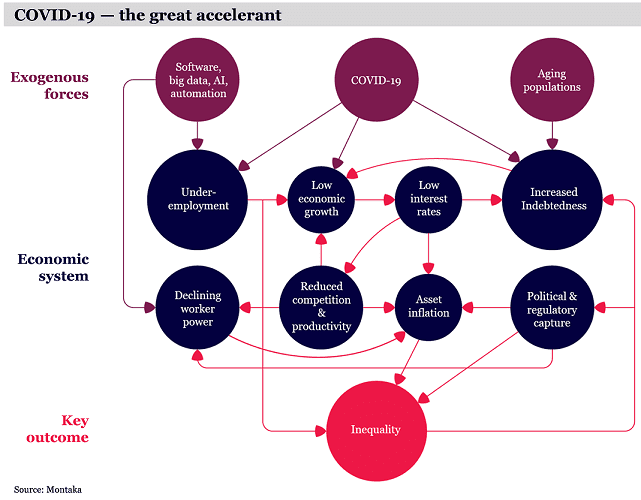

There is no doubt that inequality is being driven by an economic system in which structural forces such as technology, indebtedness, globalisation and demographics deliver low interest rates, low growth, and asset price inflation.

Other drivers – falling competition and productivity, political and regulatory capture, and declining worker power – are also creating ‘feedback loops’ that compound the dynamics above.

A natural result of this system is higher inequality, as wealth gains importance and power, while the middle and lower classes struggle to raise their incomes and maintain living standards.

Unpleasant side-effects

Growing inequality is leading to a number of adverse economic and political side effects.

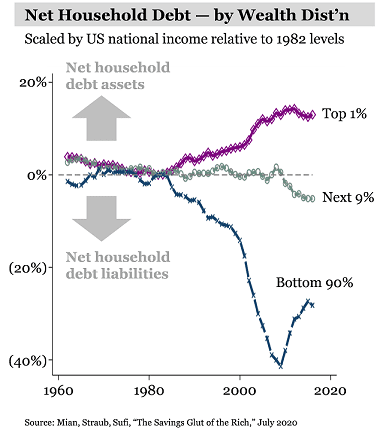

The first is rising indebtedness. The wealthy can’t spend all their income, so instead use it to accumulate more assets. The value of these assets, however, is underpinned by the continued consumption of lower income earners – which can only be effected with additional borrowings, given their income stagnation. But should borrowers reduce spending to make payments on their debt, then aggregate economic growth deteriorates.

Inequality heightens financial risk. With lower income earners heavily indebted, this higher leverage exposes the economy to a greater risk of financial crises.

Inequality also increases political instability. The wealthy can use their growing power to influence Government and politicians. It can also cause political parties to ramp up rhetoric that leads to social division.

COVID-19 accelerant

Over the long run, we expect COVID-19 to act as an accelerant to an economic system that was already driving inequality higher.

For a start, COVID is disproportionately hurting low-income earners. Between March and July, 2020, 28 per cent of workers in families making less than US$40,0000 a year were laid off, considerably higher than the 13 per cent of workers from families with incomes over $100,000 a year.

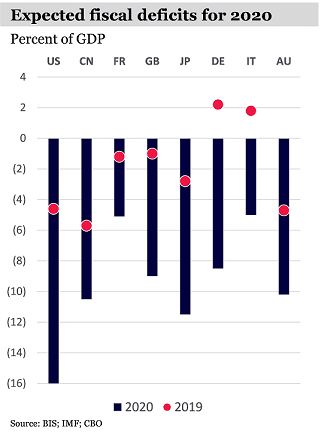

COVID is also leading to increased indebtedness – particularly at the government level. Across the board, fiscal deficits for 2020 are blowing out. In the US, for example, the level of deficit spending (as a proportion of GDP) has not been experienced since 1945.

This debt will likely exacerbate the low-growth, low-interest rate environment that elevates the relative importance of wealth accumulated in the past and that exacerbates the political side-effects of inequality.

Five investment implications

So how do investors prepare for a world of growing inequality? We believe there are five things investors should do to navigate this landscape.

1. Favour equities over fixed income assets

The economic environment described above is perversely favourable for equities (and highly unfavourable for fixed income assets). The most plausible long-term path out of our global mountain of indebtedness is via financial repression.

Financial repression will see real interest rates remain depressed (and likely negative) for an extended period. This is a painful environment for fixed income assets and a wonderful environment for equities.

2. Focus on businesses generating high-quality growth

It is logical to own businesses which can deliver high-quality growth. In the low growth world that naturally results from the current economic system, the most resilient and sustainable growth stories are those which relate to ‘penetration’ or ‘disruption’ of existing large addressable markets, rather than those which derive their growth from the broader economy. The biggest sustainable growth story taking place right now is the digital transformation of the enterprise, in our view.

3. Seek a sustainable data advantage

Investors should own those businesses that have sustainable and growing data advantages and are winning from the new technology this data unlocks. Similarly, those businesses being disrupted by these new forms of technology should be avoided.

Obvious examples of businesses with growing data advantages include Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet. Less obvious examples include Spotify, Blackstone and UnitedHealth.

4. Invest in businesses with wealthy customers

In a time of accelerating inequality, companies with wealthier customers are preferable and more likely to deliver the high-quality growth we seek.

On the consumer side, Apple has demonstrated the enormous value of a relatively wealthier customer base (versus, say, the Android customer base); as has Salesforce and ServiceNow on the corporate/enterprise side.

5. Buy businesses contained in borders

And finally, investors should prefer businesses which are contained within borders, or stable economic blocs.

Higher inequality increases cross-border trade imbalances, and we see a high probability of ongoing economic nationalism, trade disputes, as well as a likely decoupling with China – at least along the dimensions of critical technology and data.

Microsoft dominates the world outside of China in cloud-based platforms and productivity applications, for example. While Alibaba and Tencent dominate the Chinese mainland in cloud, e-commerce, digital advertising and gaming, for example. The cross-border overlap here is favourably minimal.

Prepare your portfolio

There is no doubt that growing inequality is one of the major trends of our era. And it is accelerating post-COVID-19. Inequality doesn’t just have social implications, it has economic and investment implications as well.

The Gilded Age eventually ended and after World War II as we entered a new period of equality. We don’t know how long this new ‘Gilded Age’ of growing inequality will continue, nor how it will end.

But investors need to prepare their portfolios to navigate a landscape of low-growth, low interest rates, and rising inequality.

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer at Montaka Global Investments. This article is based on a new in-depth Montaka research paper titled Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality which can be found here.

5 ways to build investment portfolios amid growing inequality

-Andrew Macken

Most investors are aware that COVID-19 is accelerating economic forces such as indebtedness, low interest rates and asset price inflation. But there is perhaps less awareness of another powerful trend that COVID is also accelerating: the ‘Gilded Age’-style economic inequality that has been emerging in recent decades.

Inequality is an important consequence of our economic system, and we see it becoming more extreme in a post-COVID world.

Growing inequality will lead to slower economic growth, even more indebtedness, increased financial risk, and greater political instability. These are all factors that will have a significant impact on investors’ portfolios.

Inequality creates winners and losers. And there are key steps that investors can take to be on the right side of these changes – to not only protect their portfolios from accelerating inequality, but also generate strong investment returns into the future.

The return of the Gilded Age

At the start of the 20th Century, the world was in the grip of the ‘Gilded Age’ as described by Mark Twain. Plutocrats accumulated vast fortunes and economic inequality surged as the top 1% captured a disproportionate share of income from wages and capital.

Following two world wars, this inequality reduced dramatically with higher taxes, weak asset prices, and financial repression by governments. That continued for three generations.

But inequality began to return in the 1980s and 1990s, driven by ‘super managers’ – corporate executives earning huge wages and bonuses. And we now have a new era of billionaire plutocrats such as Gates, Bezos and Musk. Indeed, some historians are calling our current economic situation the ‘New Gilded Age’.

The US has found itself back to pre-WWII levels of inequality. The top 1 per cent capture more than 20 per cent of total income, up from 10 per cent just 40 years ago. What’s more, that doubling of income flowing to the top 1 per cent came from the bottom 50 per cent. More recent data from the US Federal Reserve suggests that over 30 per cent of total wealth is attributable to the top 1 per cent in the US.

There is no doubt that inequality is being driven by an economic system in which structural forces such as technology, indebtedness, globalisation and demographics deliver low interest rates, low growth, and asset price inflation.

Other drivers – falling competition and productivity, political and regulatory capture, and declining worker power – are also creating ‘feedback loops’ that compound the dynamics above.

A natural result of this system is higher inequality, as wealth gains importance and power, while the middle and lower classes struggle to raise their incomes and maintain living standards.

Unpleasant side-effects

Growing inequality is leading to a number of adverse economic and political side effects.

The first is rising indebtedness. The wealthy can’t spend all their income, so instead use it to accumulate more assets. The value of these assets, however, is underpinned by the continued consumption of lower income earners – which can only be effected with additional borrowings, given their income stagnation. But should borrowers reduce spending to make payments on their debt, then aggregate economic growth deteriorates.

Inequality heightens financial risk. With lower income earners heavily indebted, this higher leverage exposes the economy to a greater risk of financial crises.

Inequality also increases political instability. The wealthy can use their growing power to influence Government and politicians. It can also cause political parties to ramp up rhetoric that leads to social division.

COVID-19 accelerant

Over the long run, we expect COVID-19 to act as an accelerant to an economic system that was already driving inequality higher.

For a start, COVID is disproportionately hurting low-income earners. Between March and July, 2020, 28 per cent of workers in families making less than US$40,0000 a year were laid off, considerably higher than the 13 per cent of workers from families with incomes over $100,000 a year.

COVID is also leading to increased indebtedness – particularly at the government level. Across the board, fiscal deficits for 2020 are blowing out. In the US, for example, the level of deficit spending (as a proportion of GDP) has not been experienced since 1945.

This debt will likely exacerbate the low-growth, low-interest rate environment that elevates the relative importance of wealth accumulated in the past and that exacerbates the political side-effects of inequality.

Five investment implications

So how do investors prepare for a world of growing inequality? We believe there are five things investors should do to navigate this landscape.

1. Favour equities over fixed income assets

The economic environment described above is perversely favourable for equities (and highly unfavourable for fixed income assets). The most plausible long-term path out of our global mountain of indebtedness is via financial repression.

Financial repression will see real interest rates remain depressed (and likely negative) for an extended period. This is a painful environment for fixed income assets and a wonderful environment for equities.

2. Focus on businesses generating high-quality growth

It is logical to own businesses which can deliver high-quality growth. In the low growth world that naturally results from the current economic system, the most resilient and sustainable growth stories are those which relate to ‘penetration’ or ‘disruption’ of existing large addressable markets, rather than those which derive their growth from the broader economy. The biggest sustainable growth story taking place right now is the digital transformation of the enterprise, in our view.

3. Seek a sustainable data advantage

Investors should own those businesses that have sustainable and growing data advantages and are winning from the new technology this data unlocks. Similarly, those businesses being disrupted by these new forms of technology should be avoided.

Obvious examples of businesses with growing data advantages include Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet. Less obvious examples include Spotify, Blackstone and UnitedHealth.

4. Invest in businesses with wealthy customers

In a time of accelerating inequality, companies with wealthier customers are preferable and more likely to deliver the high-quality growth we seek.

On the consumer side, Apple has demonstrated the enormous value of a relatively wealthier customer base (versus, say, the Android customer base); as has Salesforce and ServiceNow on the corporate/enterprise side.

5. Buy businesses contained in borders

And finally, investors should prefer businesses which are contained within borders, or stable economic blocs.

Higher inequality increases cross-border trade imbalances, and we see a high probability of ongoing economic nationalism, trade disputes, as well as a likely decoupling with China – at least along the dimensions of critical technology and data.

Microsoft dominates the world outside of China in cloud-based platforms and productivity applications, for example. While Alibaba and Tencent dominate the Chinese mainland in cloud, e-commerce, digital advertising and gaming, for example. The cross-border overlap here is favourably minimal.

Prepare your portfolio

There is no doubt that growing inequality is one of the major trends of our era. And it is accelerating post-COVID-19. Inequality doesn’t just have social implications, it has economic and investment implications as well.

The Gilded Age eventually ended and after World War II as we entered a new period of equality. We don’t know how long this new ‘Gilded Age’ of growing inequality will continue, nor how it will end.

But investors need to prepare their portfolios to navigate a landscape of low-growth, low interest rates, and rising inequality.

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer at Montaka Global Investments. This article is based on a new in-depth Montaka research paper titled Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality which can be found here.

This content was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.