By Andrew Macken

There have been many attempts to explain the underlying drivers of Trump’s sweeping tariffs that have roiled global financial markets.

Trade wars obviously feel complex and seem driven by a myriad of political and economic factors.

Yet an insightful book I read five years ago, Trade Wars Are Class Wars, by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis, offers a powerful and surprisingly straightforward lens through which to understand the fundamental dynamics at play.

Pettis (a finance professor and expert on the Chinese economy) and Klein (an economics writer) argue that at the heart of trade tensions lies a crucial imbalance in global demand. And these imbalances, surprisingly, have their roots in wealth inequality.

Our concern for inequality stems from both human empathy and its effect on economic trends relevant to Montaka’s capital allocation decisions. For those interested in our last deep dive on the topic, check out our 2020 whitepaper titled ‘Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality.’

The Global Demand Imbalance: Donors and Recipients

While not obvious at first, international trade can be viewed through the lens of certain countries having insufficient demand.

When a country consistently produces more than its domestic economy can consume, it requires demand from foreign countries to absorb these excesses. (Countries in this category are said to have a ‘current account’ surplus).

These excesses are largely absorbed through international trade by ‘demand donor’ countries with economies strong enough to consume, not only their own production, but excess production from others. Their demand is effectively donated. And the size of their country’s demand donation is its ‘current account’ deficit.

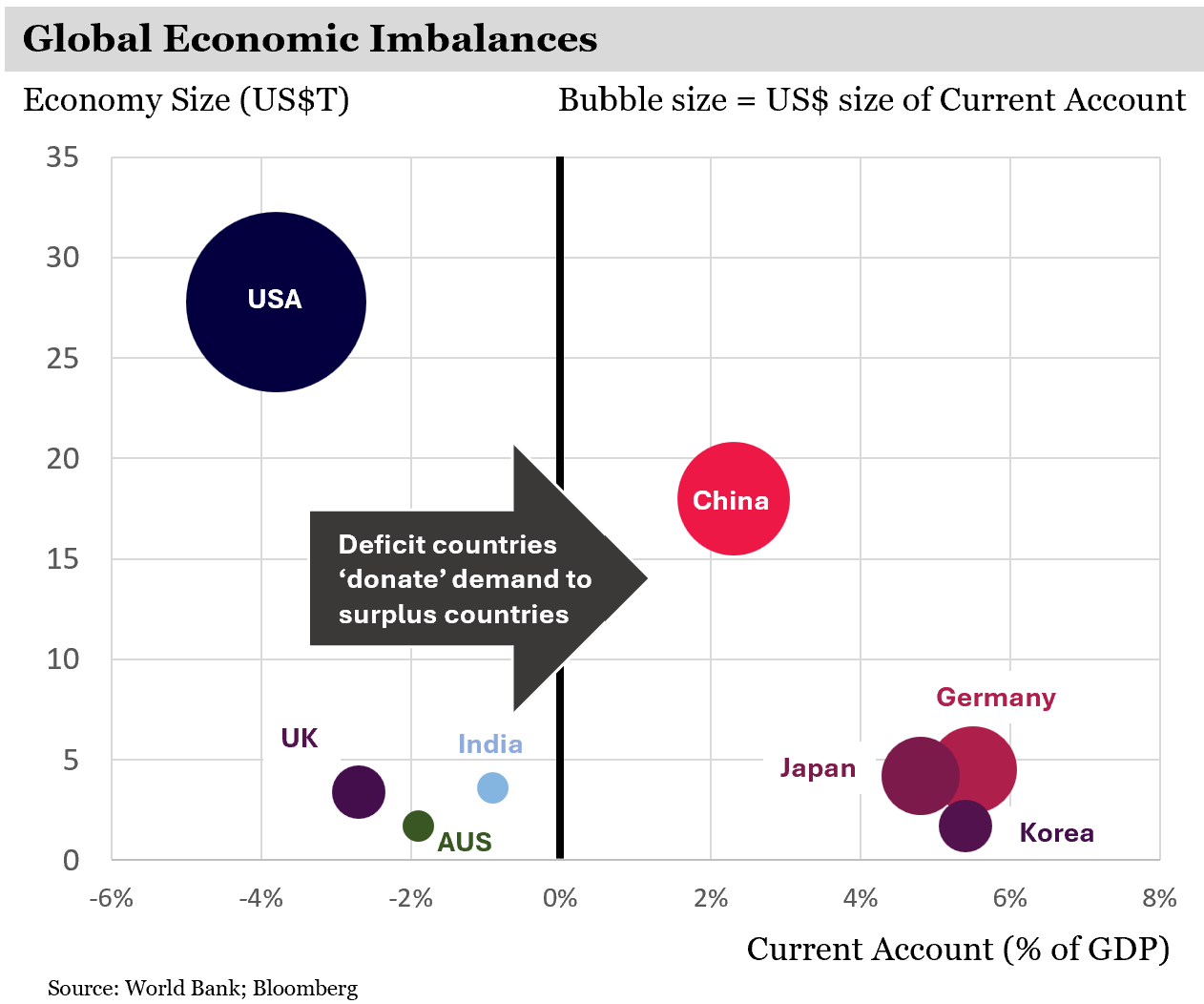

Countries like China, Germany, Japan, and Korea, which have historically run significant current account surpluses, inherently depend on demand donations from other countries to absorb their excess production.

Conversely, countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and India, which often exhibit current account deficits, effectively provide this necessary demand. They absorb the excess production of the surplus nations, preventing these economies from facing underutilization of their productive capacity.

This seemingly straightforward exchange, however, carries significant consequences – for both donors and recipients.

The Strains of Imbalances: Rising Indebtedness and Fragility

When excess production from abroad is constantly absorbed, it places considerable strain on the economies of demand-donor nations.

To sustain a level of consumption that accommodates both domestic – and foreign – production often requires a rise in domestic debt. Households, businesses, and even governments, need to borrow more to finance this higher level of consumption relative to their own production. This increasing indebtedness creates a more fragile domestic economy – one that is more sensitive to economic cycles.

As Pettis and Klein argue, these donor countries become less flexible in responding to domestic economic cycles. High levels of debt can constrain fiscal and monetary policy options during downturns, making it harder to stimulate demand and recover from recessions.

These imbalances also reduce the stability of recipient countries – those which are producing more than they can consume domestically. It means their domestic production is tied not only to their own business cycles, but to those of foreign economies as well. This makes them more vulnerable if conditions change abroad.

The Surprising Root Cause: Inequality

The crucial question then becomes: why do some countries consistently run current account surpluses – relying on the demand donations of others – in the first place?

The answer, as Pettis and Klein argue, lies in the often-overlooked issue of wealth and income inequality within these nations.

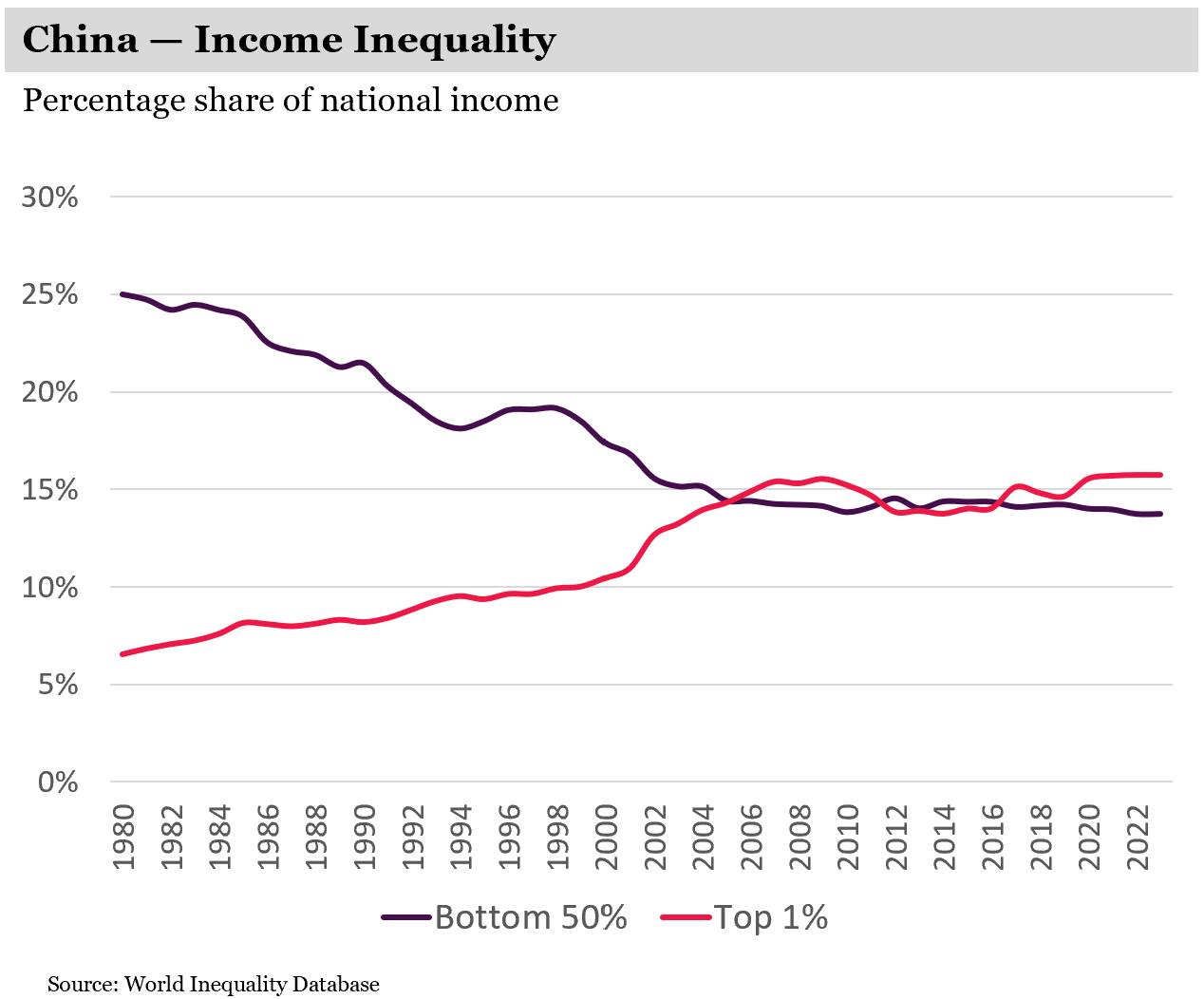

In countries where a disproportionate share of national income and wealth is concentrated among a small segment of the population, such as China, the majority of households have relatively lower levels of income to spend on consuming goods and services.

This suppressed domestic consumption means China produces more goods and services than its own population can afford to buy. Foreign markets, particularly the US, are then required to absorb the country’s excess production.

The persistent current account surpluses observed in countries like China, therefore, are a symptom of underlying wealth inequality that depresses domestic demand. Donations of demand from foreign countries are needed to maintain economic activity in the face of insufficient internal consumption.

The Path Forward: Rebalancing Through Redistribution

Trump’s drastic tariff measures – particularly those leveled on Chinese imports to the US – reflect his desire to reduce the global imbalances that require donations of demand from the US economy to the rest of the world.

Tariffs reduce demand for foreign imports by making them more expensive.

This will ultimately leave countries like China – those that produce more than their domestic economies consume – with a choice:

- Reduce domestic production (i.e., a sharp recession and significant increase in unemployment), or, more favorably

- Increase domestic consumption by transferring national income to lower-income households.

As Pettis and Klein suggest, such measures could include stronger labor protections, higher minimum wages, more progressive tax systems, and increased social safety nets.

While such a transformation would be beneficial for most citizens in surplus countries by raising their living standards, it would likely face resistance from wealthy “vested interests” – in the words of the late Chinese Premier, Li Keqiang – who have benefited from the existing system for decades.

These groups would likely oppose policies that redistribute income and wealth, fearing a reduction in their own share. This inherent conflict of interest makes the path to rebalancing a politically challenging one.

They say that politics makes strange bedfellows. And that we find ourselves in a situation in which Trump is essentially going into bat for the Chinese everyman – knowingly or not – is quite stunning. But here we are.

Addressing inequality

The core of this trade war lies in fundamental imbalances in global demand, where countries such as China, with insufficient domestic consumption, rely on ‘demand donations’ from countries like the US to purchase their excess production.

The surprising root cause of these persistent surpluses is significant wealth and income inequality within these recipient countries. Inequality leaves most domestic households with insufficient income to purchase and consume the goods and services produced domestically, which necessitates a reliance on foreign demand.

A sustainable resolution requires addressing this inequality through policies that redistribute income and wealth, thereby boosting domestic demand in recipient countries and reducing the need for foreign demand donations.

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100 or leave us a line at montaka.com/contact-us

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.

The Defining Word of the Trade War is ‘Inequality’ not ‘Tariff’

By Andrew Macken

There have been many attempts to explain the underlying drivers of Trump’s sweeping tariffs that have roiled global financial markets.

Trade wars obviously feel complex and seem driven by a myriad of political and economic factors.

Yet an insightful book I read five years ago, Trade Wars Are Class Wars, by Matthew C. Klein and Michael Pettis, offers a powerful and surprisingly straightforward lens through which to understand the fundamental dynamics at play.

Pettis (a finance professor and expert on the Chinese economy) and Klein (an economics writer) argue that at the heart of trade tensions lies a crucial imbalance in global demand. And these imbalances, surprisingly, have their roots in wealth inequality.

Our concern for inequality stems from both human empathy and its effect on economic trends relevant to Montaka’s capital allocation decisions. For those interested in our last deep dive on the topic, check out our 2020 whitepaper titled ‘Covid-19: accelerating our journey to inequality.’

The Global Demand Imbalance: Donors and Recipients

While not obvious at first, international trade can be viewed through the lens of certain countries having insufficient demand.

When a country consistently produces more than its domestic economy can consume, it requires demand from foreign countries to absorb these excesses. (Countries in this category are said to have a ‘current account’ surplus).

These excesses are largely absorbed through international trade by ‘demand donor’ countries with economies strong enough to consume, not only their own production, but excess production from others. Their demand is effectively donated. And the size of their country’s demand donation is its ‘current account’ deficit.

Countries like China, Germany, Japan, and Korea, which have historically run significant current account surpluses, inherently depend on demand donations from other countries to absorb their excess production.

Conversely, countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and India, which often exhibit current account deficits, effectively provide this necessary demand. They absorb the excess production of the surplus nations, preventing these economies from facing underutilization of their productive capacity.

This seemingly straightforward exchange, however, carries significant consequences – for both donors and recipients.

The Strains of Imbalances: Rising Indebtedness and Fragility

When excess production from abroad is constantly absorbed, it places considerable strain on the economies of demand-donor nations.

To sustain a level of consumption that accommodates both domestic – and foreign – production often requires a rise in domestic debt. Households, businesses, and even governments, need to borrow more to finance this higher level of consumption relative to their own production. This increasing indebtedness creates a more fragile domestic economy – one that is more sensitive to economic cycles.

As Pettis and Klein argue, these donor countries become less flexible in responding to domestic economic cycles. High levels of debt can constrain fiscal and monetary policy options during downturns, making it harder to stimulate demand and recover from recessions.

These imbalances also reduce the stability of recipient countries – those which are producing more than they can consume domestically. It means their domestic production is tied not only to their own business cycles, but to those of foreign economies as well. This makes them more vulnerable if conditions change abroad.

The Surprising Root Cause: Inequality

The crucial question then becomes: why do some countries consistently run current account surpluses – relying on the demand donations of others – in the first place?

The answer, as Pettis and Klein argue, lies in the often-overlooked issue of wealth and income inequality within these nations.

In countries where a disproportionate share of national income and wealth is concentrated among a small segment of the population, such as China, the majority of households have relatively lower levels of income to spend on consuming goods and services.

This suppressed domestic consumption means China produces more goods and services than its own population can afford to buy. Foreign markets, particularly the US, are then required to absorb the country’s excess production.

The persistent current account surpluses observed in countries like China, therefore, are a symptom of underlying wealth inequality that depresses domestic demand. Donations of demand from foreign countries are needed to maintain economic activity in the face of insufficient internal consumption.

The Path Forward: Rebalancing Through Redistribution

Trump’s drastic tariff measures – particularly those leveled on Chinese imports to the US – reflect his desire to reduce the global imbalances that require donations of demand from the US economy to the rest of the world.

Tariffs reduce demand for foreign imports by making them more expensive.

This will ultimately leave countries like China – those that produce more than their domestic economies consume – with a choice:

As Pettis and Klein suggest, such measures could include stronger labor protections, higher minimum wages, more progressive tax systems, and increased social safety nets.

While such a transformation would be beneficial for most citizens in surplus countries by raising their living standards, it would likely face resistance from wealthy “vested interests” – in the words of the late Chinese Premier, Li Keqiang – who have benefited from the existing system for decades.

These groups would likely oppose policies that redistribute income and wealth, fearing a reduction in their own share. This inherent conflict of interest makes the path to rebalancing a politically challenging one.

They say that politics makes strange bedfellows. And that we find ourselves in a situation in which Trump is essentially going into bat for the Chinese everyman – knowingly or not – is quite stunning. But here we are.

Addressing inequality

The core of this trade war lies in fundamental imbalances in global demand, where countries such as China, with insufficient domestic consumption, rely on ‘demand donations’ from countries like the US to purchase their excess production.

The surprising root cause of these persistent surpluses is significant wealth and income inequality within these recipient countries. Inequality leaves most domestic households with insufficient income to purchase and consume the goods and services produced domestically, which necessitates a reliance on foreign demand.

A sustainable resolution requires addressing this inequality through policies that redistribute income and wealth, thereby boosting domestic demand in recipient countries and reducing the need for foreign demand donations.

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.This content was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.