|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

-George Hadjia

Investment returns in the long run are dictated by two factors: earnings growth and changes in the earnings multiple. Many high-flying businesses today are trading at exorbitant multiples. What are the implications of this for long-run annual returns for those stocks?

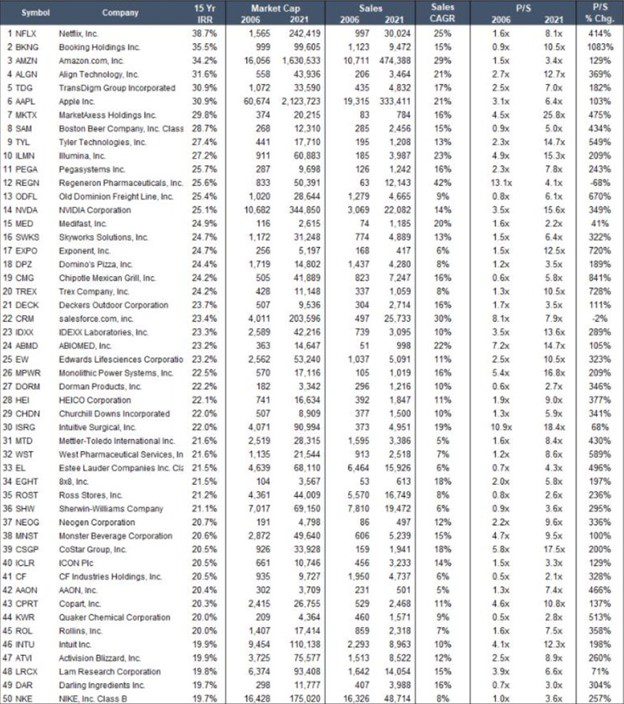

Consider the table below. It shows the 15-year internal rate of rate (IRR) for the 50 best performing stocks.

Source: Saga Partners

From this table there are two key metrics to observe: the sales CAGR as well as the change in the price/sales ratio (which would more correctly have been represented as EV/sales, but the direction of the change in the multiple is what we are interested in here).

Note that almost all of the businesses on the list had healthy double-digit sales annual growth rates over the 15-year period. This is remarkable when you consider the enormous sales base of some of these companies in 2006. Amazon and Apple, for example, had sales of $10.7bn and $19.3bn in 2006, yet they still grew sales at a 29% and 21% annual rate, respectively. It is also worth pointing out that every single company on this list had positive sales growth rates on average over the 15-year period. In the long run, it’s virtually impossible to earn an investment return far in excess of the performance of the underlying business. In this sense, it’s crucial to identify and invest in businesses capable of growing their revenues and earnings power at a healthy clip.

So far we’ve focused on sales growth (which ideally also drives an even greater level of earnings growth). But this doesn’t tell the whole story of why these stocks were the best performers. We also need to think about the movement in the multiple.

Multiples are a simplified, abbreviated way of thinking about value. They don’t tell the whole story, but changes in the level of multiples reflect shifting investor views around the prospects of a stock. For example, if a business that has historically grown at 5% per annum executes well on its growth strategy and is then assessed to be able to grow at 10% per annum in the future, the market will be willing to pay more for this growth. Investors will thus ascribe a higher earnings multiple to this company to reflect the fact that it is growing faster. The opposite is also true if expectations for growth are revised downward.

As a company grows, the law of large numbers begins to act as an anchor on the growth rates that the business is able to achieve. As they say, trees don’t grow to the sky, and no company can grow at double-digit rates forever. At some point, the growth will begin to slow, and as investors process this maturation in the growth profile of the business, they seek to pay less for this future stream of earnings, and the multiple thus compresses.

If we refer again to the table above, we can observe that only salesforce.com and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals saw their P/sales multiple compress over the 15 year period. The multiple de-rate was made up for by insane sales CAGRs over the 15 years (30% and 42% for salesforce.com and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, respectively). This means that there was multiple deflation for only 4% of the 50 best performing stocks.

If we invert this, 96% of the best performers required multiple expansion as a big driver of their IRRs over the 15 years. The corollary of this is that many stocks today with stratospheric EV/sales ratios will inevitably see multiple compression. If you buy a stock at 50x EV/sales it’s an almost certainty that it will not trade at 50x in 10-15 years. This can be problematic.

Assume your stock is growing sales at 30% per annum. Great! If the multiple remains at 50x in 15 years we will have achieved a 30% IRR. That would be an enviable result. But the multiple won’t remain at 50; it will compress. If it the stock instead trades at 10x EV/sales at year 15, the IRR drops to around 17%. At 5x sales it falls to 12%. While mathematically the rate of intrinsic value growth matters more than the multiple you pay, there are limitations to this.

If you drastically overpay for a stock it might require unachievable levels of underlying business growth to achieve an acceptable (or even positive) IRR. I wonder how many investors will learn this the hard way: there is such a thing as too high of a price for a wonderful business.

George Hadjia is a Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.