|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

While everyone is focused on a Chinese economic slowdown and the risk of a currency devaluation – and rightly so – we are increasingly concerned with the state of the Italian financial system. By financial system, we mean to include the banking system and the state of the government balance sheet.

As you will see, the Italian economy is weak, the banking system is in distress and government borrowings are too large to “bail-out”. Much of this is not new and has been the state of affairs for many years now. Yet recent and potential future policy decisions are giving cause for concern that a day of reckoning is approaching.

Given the interconnectedness of the European Monetary Union, any major hiccup in Italy would have severe consequences for the EU and the global financial system more broadly.

Italy is too big to “bail”

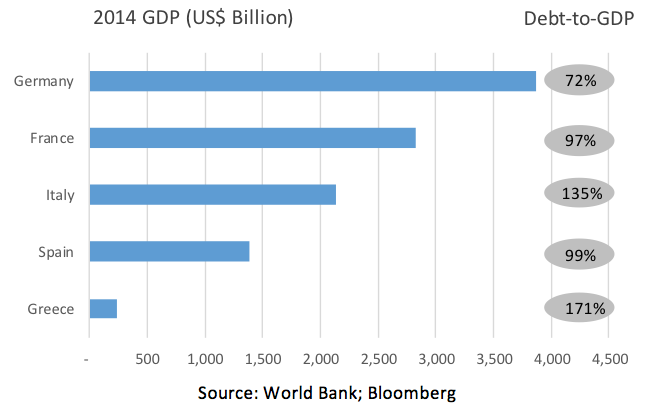

- We all remember the turbulence that Greece caused financial markets when it needed a bailout package following years of financial distress and a severe economic downturn.

- Well, it should be remembered that, in the scheme of European economies, Greece is actually very small. Bailing out Greece was at least an option by larger economies.

- By comparison, Spain’s economy is six times larger than that of Greece’s. Italy’s is nine times larger. And Italy’s ratio of government debt to GDP is currently 135% – a level which almost ensures it cannot grow its way out of its indebtedness.

- If there is major crisis in the Italian financial system, it cannot be bailed out. Instead, assets will surely need to be written down.

Italy has had structural deficiencies for a long time

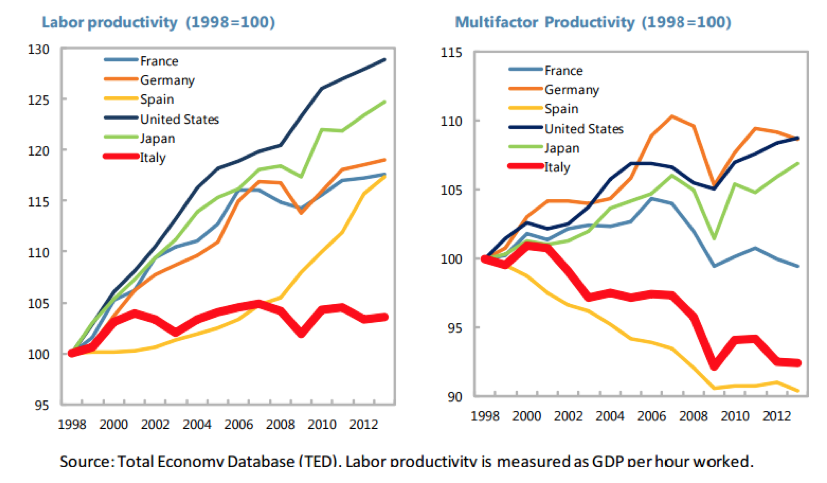

- Italy’s economy was not on a particularly sound footing even before the Global Financial Crisis. As illustrated below, Italy has lagged other European economies on multiple measures of productivity – a key driver of GDP growth.

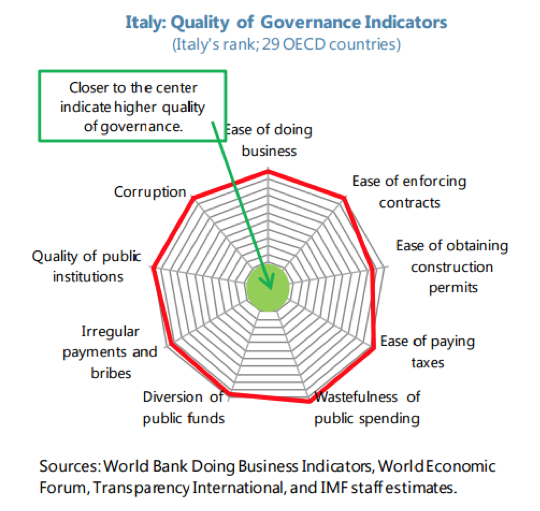

- Also as illustrated below, the World Bank and IMF rate Italy’s overall quality of governance as poor on nearly every dimension. This is surely a key contributor to the weak productivity measures shown above.

Italy’s economy has struggled since the Global Financial Crisis

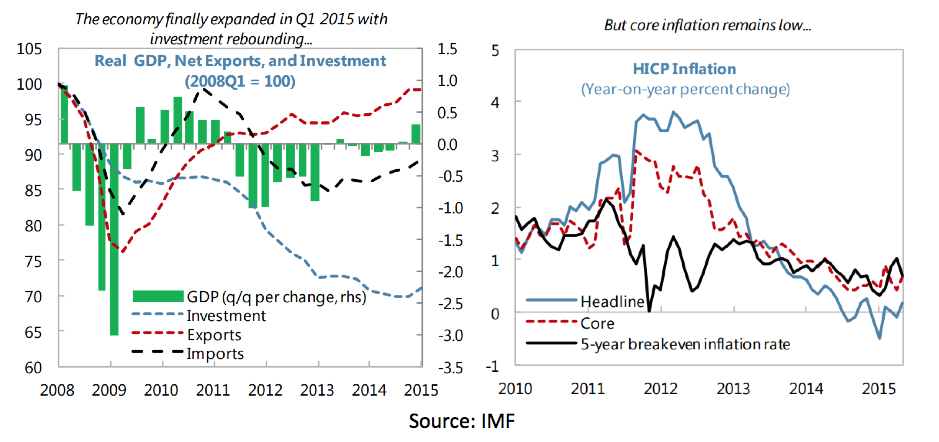

- Since the GFC, Italy’s economic growth has been negative for most quarters with investment falling steadily since 2008.

- Inflation today remains very low – despite multiple years of ECB quantitative easing. Indeed, the current one-year inflation rate implied by bond markets is negative 0.6 percent!

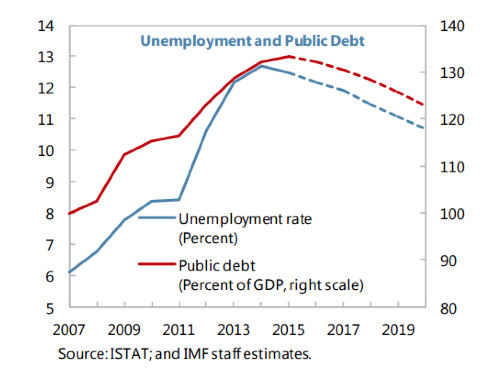

- The unemployment rate reached nearly 13% in 2014 and currently stands at 11%.

Italy’s government indebtedness appears unsustainable

- At 135% of GDP, or approximately €$2.2 trillion, the level of borrowings by the Italian government is enormous. It is enormous both in absolute terms; and relative to the potential tax revenue that can be generated domestically to service the debt.

- High levels of government debt can be problematic in general because the interest repayments and ultimate debt reduction consumes government tax revenue which would otherwise have been spent on the nation. Furthermore, the government in question often needs to reduce spending to make debt repayments which creates a drag on the nation’s economic growth.

- When debt levels are high, nations can find themselves in a “debt spiral”. To increase debt repayments, the government reduces spending, which creates a drag on the economy, which in turn reduces tax revenues, which requires more cuts in spending, thereby creating an even bigger drag on the economy, and so on.

- To reduce a nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio, the rough rule of thumb is the following:

- GDP growth + primary budget surplus > government bond yield x debt-to-GDP.

- This is basically just a way of saying: the growth in government income that can be used to pay interest expense > growth in interest expense.

- For Italy, the left hand side of this equation is around 1.9%, given nominal GDP growth of about 0.4% and a primary budget surplus of 1.5%. But unfortunately for Italy, the right hand side of the equation is also around 1.9%, based on a 10YR government bond yield of 1.4% multiplied by 135% debt-to-GDP ratio.

- This implies that Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio will stand still; or increase, to the extent Italy’s bond yields rise in the future.

Italy’s banking system has a non-performing-loan problem

- Before examining the credit quality of the loan assets in the Italian banking system, two important points should be made with respect to the structure of the Italian economy:

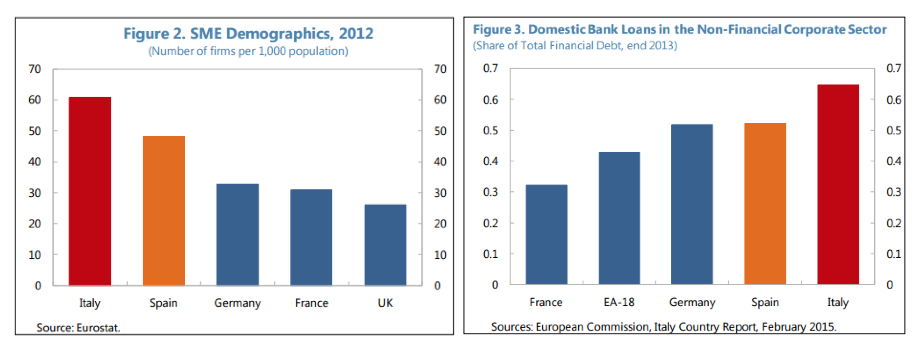

- The Italian economy, more so than other EU economies, comprises a large share of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). SMEs, by their nature, are typically not as productive or profitable as larger firms; nor do they have the financial resources to be able to weather a downturn as well as their larger peers.

- Italian firms are, by and large, financed by Italian banks. In this sense, the Italian banking system is very inward-focused – meaning they are heavily exposed to the domestic economic downturn, rather than being more diversified across the EU, for example.

- According to the European Banking Authority, approximately 17% of all Italian loans are non-performing. We estimate that these non-performing loans equate to more than US$800 billion – again, a level far too big to “bail out”.

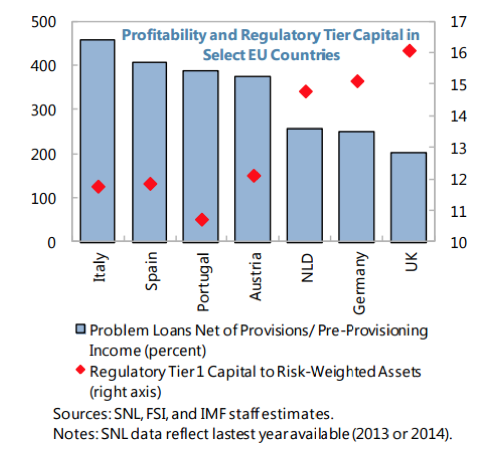

- As illustrated by the chart below, Italy’s bad loans relative to banking income are the highest in the EU; while regulatory Tier 1 Capital relative to Risk-Weighted-Assets is near the lowest.

- Remember, capital is designed to absorb losses so creditors and depositors can sleep at night knowing their capital can be safely repaid. Insufficient capital calls into question the solvency of the Italian banking system.

- Poor credit quality also has very real consequences for the economy more broadly. It results in organically generated capital by the banking system to be used towards absorbing bad loans. This is instead of the capital being used to extend new loans to the SMEs and households that drive the broader growth of the economy.

Regulatory risk-weightings on some banking assets seem inappropriate

- Broadly speaking, the amount of regulatory capital a bank is required to hold against an asset to protect its solvency in a worst-case scenario equals: the value of the loan asset, multiplied by the risk-weighting, multiplied by the regulatory capital ratio.

- The key point here is that the risk-weighting is the asset-specific factor that drives how much capital needs to be held against that particular asset.

- The problem in the EU, however, is that many sovereign bonds that arguably carry some default risk are held on bank balance sheets with near-zero risk weightings. That is, hardly any capital is being held to protect bank creditors (or national taxpayers) in the event of a sovereign write-down.

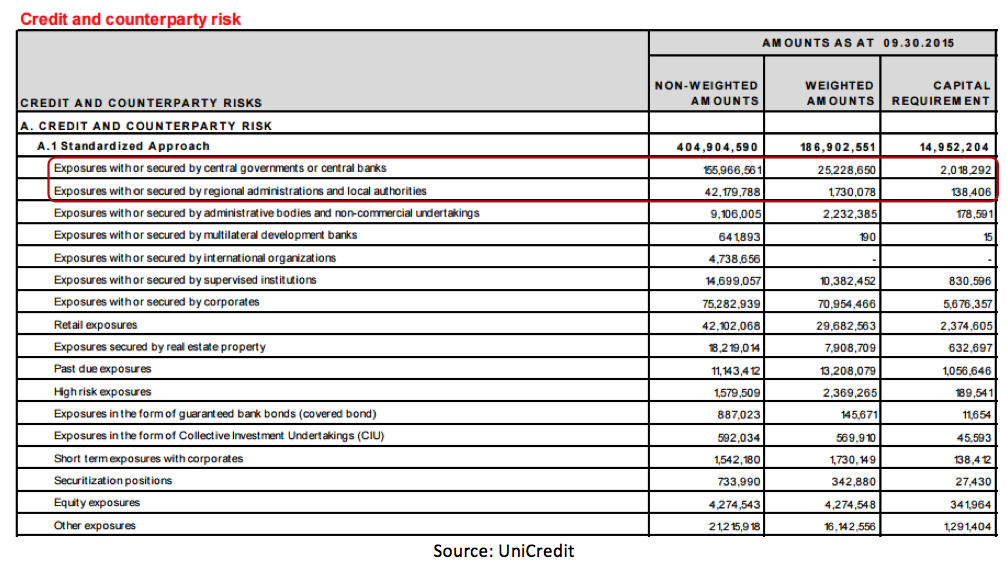

- For example, consider UniCredit (Borsa Italiana: UCG), Italy’s second-largest bank by market capitalization. On September 30, 2015 (the date of the bank’s most recent regulatory filing), UniCredit was holding €198 billion in credit exposures “with or secured by” central governments, central banks, regional administrations or local authorities. Yet against these exposures, just €2.1 billion in capital was required to be held by the bank to protect its solvency from losses in these assets. Simple math says that only a 1 percent write-down in these assets would wipe out the capital that is being held to protect the bank against loss.

New “bail-in” rules risk a potential run on banks that become distressed

- Beginning on January 1, 2016, new rules under the EU’s Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD)[1] came into effect that specify burden-sharing in the event of a bank failure.

- These bail-in rules require that existing stakeholders – namely shareholders, junior creditors and even senior creditors and depositors (in excess of the guaranteed amount of €100k) – are required to contribute to the absorption of losses and recapitalization of the bank.

- Given these new rules, it is not unreasonable to expect the depositors of a financially-distressed bank to rapidly withdraw their deposits and place them in a safer bank – which in the aggregate would create a “run” on that bank.

- The concept could even be extended to the national level: if depositors in Italy, for example, believed their entire banking system was at risk, then it would not be unreasonable to expect Italians to withdraw their deposits en masse and place them in a “safer” jurisdiction, such as Germany. Of course, such collective action would seal the fate of the Italian banking system.

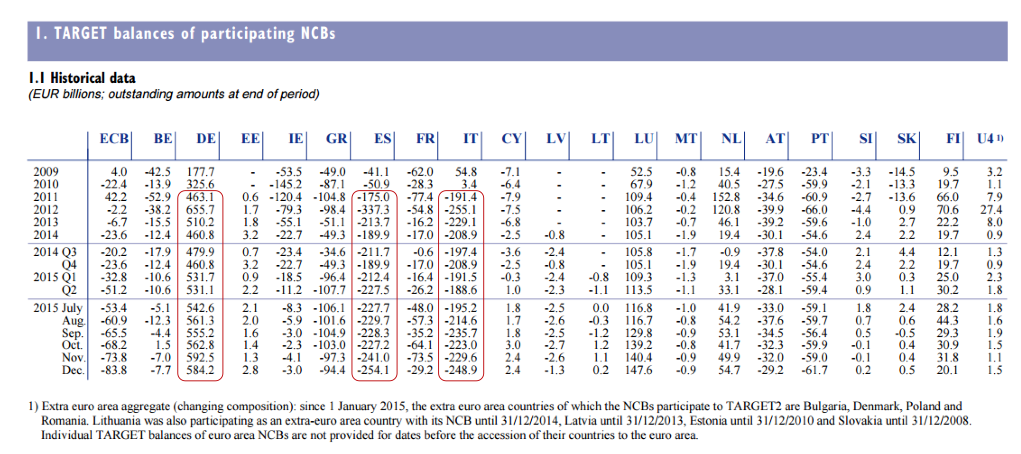

- Indeed, this dynamic started to occur back in 2011 when fears of an EU break-up first emerged. This can be observed in the European Central Bank’s disclosure of “TARGET[2] balances” of the various National Central Banks of the EU. These are cross-border payment flows.

- These balances over time illustrate: (i) large outflows of deposits from Italy and Spain starting in 2011; and large build-ups of deposits in Germany starting at the same time.

- Until recently, these imbalances were actually improving, possibly suggesting a reversal of any fears of an EU break-up or Italian or Spanish bank-run. Then, just months ago, we observed the resumption of deposit outflows from Italy and Spain to Germany. Any further acceleration in this deposit-flight would be a worrying sign.

So why does this matter now?

- Many of the points raised above are not particularly new and have persisted for years. So why should we be particularly concerned now?

- Well, we cannot predict the future. All we can do is assess the possible scenarios that may unfold as well as the likelihoods of said scenarios. And there are a number of current and prospective events that suggest to us that the likelihood of a downside Italian scenario is increasing.

- The first is “Brexit”, or the risk that Britain will exit the EU. Indeed, Prime Minister David Cameron has set the date for a referendum to decide just that on June 23, 2016. A “Yes” vote would, among other things, increase the likelihood that the EU starts to break-up. After all, if Britain can leave, others surely can too. (Note: we expect Britain will vote No, but assess the probability of a Yes vote to be well above zero).

- Indeed, even if Britain remains in the EU, they will do so under new terms negotiated by Prime Minister Cameron. This alone has opened the door to other nations doing the same – which only increases the risk of an eventual break-up down the road.

- The second is the increased prospect of deposit-flight out of weaker nations into stronger nations such as Germany. As we addressed above, the risk of this dynamic has increased significantly, in our view, since the new “bail-in” rules under the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive came into force on January 1, 2016.

- Finally, the third reason we are more concerned now than we have been in the past relates to the ongoing immigration crisis in the EU. In the first two months of 2016 alone, over 110k migrants have arrived in Greece by sea as a result of the Syrian crisis. This figure is up 28x on the same period last year, according to the International Organization for Migration.

- At the writing of this memo, neighbouring countries to Greece and Italy were closing off their borders, trapping migrants in Greece. This goes against the Schengen Agreement which is fundamental to the EU.

- This is yet another illustration of the fragility of the Union – with no sign of these crises abating any time soon.

We highlight the Italian financial system as an increasingly concerning risk that we are monitoring closely. We cannot predict if a crisis is imminent, though recognize the large impact it would likely have on EU economies and financial markets globally.

![]()

Andrew Macken is a Portfolio Manager with Montgomery Global Investment Management. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

[1] The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) establishes a common approach within the European Union (EU) to the recovery and resolution of banks and investment firms.

[2] TARGET stands for Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System