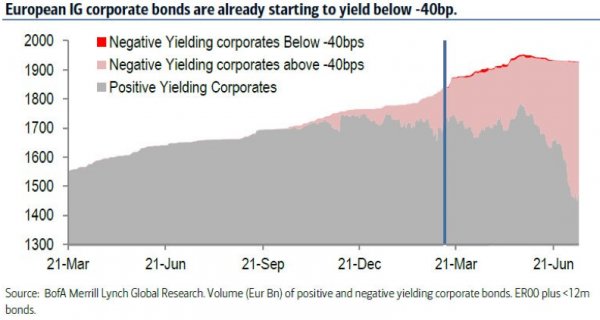

How to make sense of the strange new financial world in which we find ourselves? It is a seriously challenging question. There is currently around US$15 trillion of negatively yielding government bonds in the marketplace. Furthermore, some corporates have started issuing debt at negative yields (as shown below). This is unprecedented.

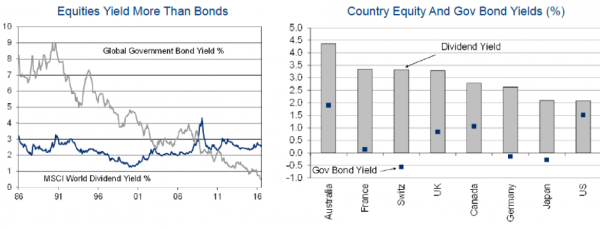

With yields in global bond markets at all-time lows, investors have been turning to the equity markets. As shown in the chart below, With the MSCI World’s dividend yield at around 2.5% per annum, this is substantially higher than what is yielded by many government and corporate bonds.

Source: Citi

Source: Citi

Furthermore, global investors scour the world for higher yielding bonds. Australia actually stands out as having both an above-average government bond yield and equity dividend yield. This is one of the reasons why the Australian dollar has remained strong in recent months (in our view): investors can borrow cheaply in foreign countries and invest in Australia. This is known as a “carry trade” and serves to drive up demand for Australian currency.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of a corporate CFO for one moment. If your company can issue debt at near zero (or even negative) yields, then surely you would be remiss for not issuing. So you go out to the market and raise costless money: now what? Well you need to deploy that money somewhere. Your choices are, broadly speaking: (i) invest it to expand your business; (ii) buy another company; or (iii) buy back stock and/or pay a special dividend.

In considering option (i), you need to assess the demand growth for the goods and/or services your company produces. But the world has been short of aggregate demand for many years now. Indeed, it is this very lack of aggregate demand that has been one of the primary drivers of low interest rates to begin with. So most corporates have not opted for option (i).

Options (ii) and (iii) have been far more popular. Almost on a daily basis, we are seeing new acquisitions. And these are not necessarily high quality and/or cheap businesses: Meda (NASDAQ: MEDAA), ADT Corp (NYSE: ADT), Arm Holdings (LSE: ARM), LinkedIn (NYSE: LNKD), Outerwall (NASDAQ: OUTR), Joy Global (NYSE: JOY), WhiteWave Foods (NYSE: WWAV) and Mattress Firm (NASDAQ: MFRM) – just to name a few.

What is the calculus here for such acquisitions? Well in some cases there are genuine synergies associated with combining the two businesses – such as in the case of Microsoft acquiring LinkedIn. In other cases, the calculus is simply as follows: I can borrow at (or near) zero; and the acquired business will likely yield me greater than my borrowing costs. Ipso facto, the deal creates value.

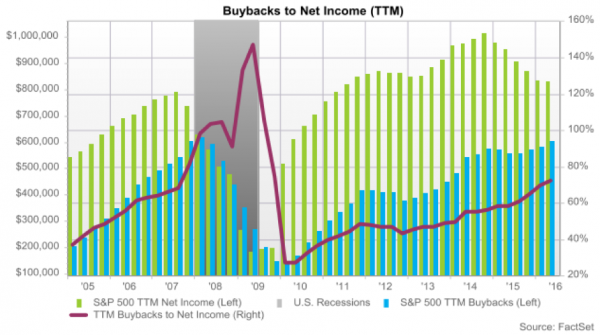

Option (iii) has also been wildly popular for many years now. The calculus is almost the same as above: I can borrow at (or near) zero; and the yield on my stock is greater than my borrowing costs. Ipso facto, the share buy backs make sense.

Believe it or not, even some central banks are making the same calculus and buying stocks or equity ETFs to generate a slightly higher yield on their assets. This is unusual because central bank assets are what effectively “back” the currency of its respective nation. Assets therefore are typically limited to ultra-safe categories – not equities.

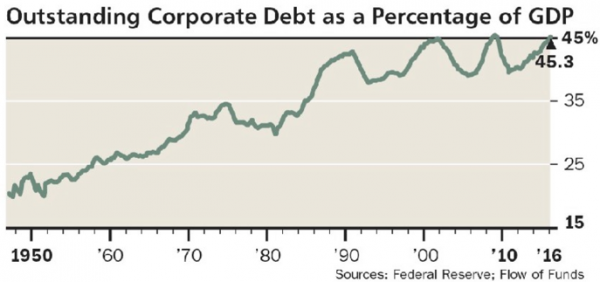

So with corporates borrowing to acquire businesses and buy-back stock, it is not surprising that we are seeing a build-up of debt on corporate balance sheets. The data below shows US corporate debt relative to GDP going back around 70 years. It is currently at record levels.

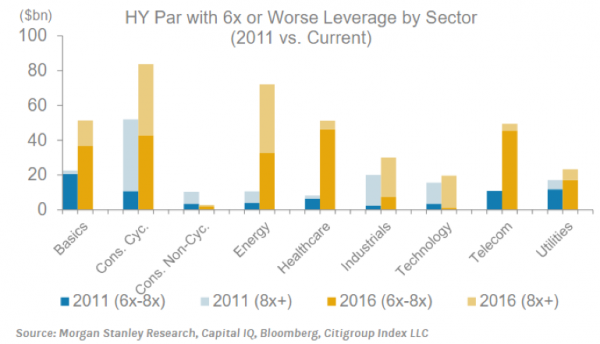

And what is perhaps the most interesting and important segmentation of the data is shown below. This data looks at the build-up in debt on the balance sheets of already-levered corporates over the last five years. The two shades of the same colour delineate between corporates with 6-8x net-debt-to-EBITDA; and >8x net-debt-to-EBITDA. Across nearly all industries, heavily indebted corporates have become significantly more heavily indebted.

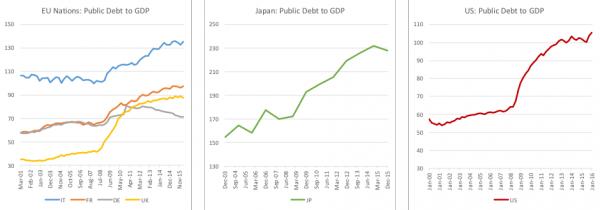

Now this is an interesting theme and is not limited to corporates. Heavily-indebted governments have also become even more heavily-indebted over recent years. We can see this clearly in the charts below that illustrate the ratio of public-debt-to-GDP for a handful of large global economies. Across the board (with the recent exception of Germany), government indebtedness has been increasing.

Source: Bloomberg

Similar to in corporate land, the argument for governments goes something like this: as interest rates fall, one’s effective borrowing capacity increases. As interest rates fall, more can be borrowed to result in the same interest expense.

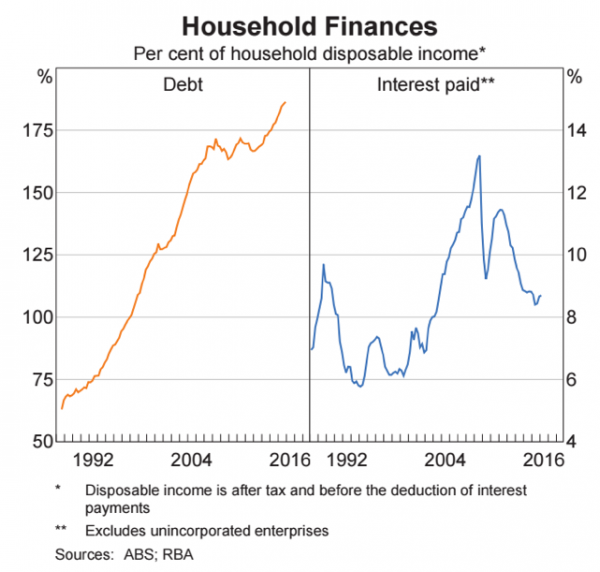

And, of course, many households in certain parts of the world – such as Australia – are making this same calculation. As shown below, note the structural increase household debt as a percentage of disposable income; yet interest paid has actually decreased in recent years as a percentage of disposable income. That is: as interest rates fall, household borrowing capacity increases. And from a mathematical perspective, this argument is valid.

But take this argument to its logical extreme: imagine that all governments, corporates and households increase their borrowings to their newly increased capacities. What might be the result of this behaviour? Well, as borrowings increase, so too would asset values: stocks, bonds and property included. The reason? More money is chasing the same available assets, so asset prices must rise. (This has been the global modus operandi for many years now).

This might sound good – especially if you are currently an owner of stocks, bonds and/or property. But what happens if interest rates start to rise? Naturally, asset prices would likely fall. But perhaps the more important question that we are grappling with is as follows: is it even possible for interest rates to rise? Does the incursion of large levels of debt ensure that rates cannot rise?

To understand why we are even asking such a seemingly absurd question, consider a scenario in which interest rates around the world increase uniformly. What would be the consequences?

- Asset prices of stocks, bonds and property would likely fall significantly. This would likely create a negative “wealth effect” in which asset owners feel less wealthy and constrain consumption. This is deflationary.

- Government borrowing costs would increase. This means more tax dollars would be diverted to the paying of interest rather than on spending and investment. The result of this must be higher taxes or lower government expenditures. Both are also deflationary.

- Many debts (including government, corporate and household) would likely become impaired creating capital shortfalls in global banking systems. Capital shortfalls result in reduced lending – which, in turn, is deflationary.

Any of the above would likely result in ultra-low interest rates to combat deflation. So either rates stay low; or rates rise and create a set of conditions that force rates lower again. This is the argument. We believe it is worth considering, at the very least.

Indeed, perhaps the only scenario in which rates can increase is a scenario in which inflation expectations remain sustainably elevated. There are probably only two ways this scenario can eventuate: (i) via increased growth expectations from a large and sustained fiscal stimulus – funded by new borrowings; or, even more potent (ii) via increased growth expectations from a large and sustained fiscal stimulus – funded by money printing (known as a Money Financed Fiscal Program – or Helicopter Money).

Either way, any fiscal stimulus that eventuates (if any) will need to be large enough to offset the deflationary consequences of rising interest rates described above. It is not clear that such a fiscal stimulus package is either likely or possible – especially one that is funded by pure money printing.

In the meantime, we would not be surprised if low rates kept edging lower and asset prices kept edging higher. We are in unprecedented financial territory today. Investors need to remain diversified, invested and protected.

Andrew Macken is a Portfolio Manager with Montgomery Global Investment Management. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Andrew Macken is a Portfolio Manager with Montgomery Global Investment Management. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Will our debts keep rates low?

How to make sense of the strange new financial world in which we find ourselves? It is a seriously challenging question. There is currently around US$15 trillion of negatively yielding government bonds in the marketplace. Furthermore, some corporates have started issuing debt at negative yields (as shown below). This is unprecedented.

With yields in global bond markets at all-time lows, investors have been turning to the equity markets. As shown in the chart below, With the MSCI World’s dividend yield at around 2.5% per annum, this is substantially higher than what is yielded by many government and corporate bonds.

Furthermore, global investors scour the world for higher yielding bonds. Australia actually stands out as having both an above-average government bond yield and equity dividend yield. This is one of the reasons why the Australian dollar has remained strong in recent months (in our view): investors can borrow cheaply in foreign countries and invest in Australia. This is known as a “carry trade” and serves to drive up demand for Australian currency.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of a corporate CFO for one moment. If your company can issue debt at near zero (or even negative) yields, then surely you would be remiss for not issuing. So you go out to the market and raise costless money: now what? Well you need to deploy that money somewhere. Your choices are, broadly speaking: (i) invest it to expand your business; (ii) buy another company; or (iii) buy back stock and/or pay a special dividend.

In considering option (i), you need to assess the demand growth for the goods and/or services your company produces. But the world has been short of aggregate demand for many years now. Indeed, it is this very lack of aggregate demand that has been one of the primary drivers of low interest rates to begin with. So most corporates have not opted for option (i).

Options (ii) and (iii) have been far more popular. Almost on a daily basis, we are seeing new acquisitions. And these are not necessarily high quality and/or cheap businesses: Meda (NASDAQ: MEDAA), ADT Corp (NYSE: ADT), Arm Holdings (LSE: ARM), LinkedIn (NYSE: LNKD), Outerwall (NASDAQ: OUTR), Joy Global (NYSE: JOY), WhiteWave Foods (NYSE: WWAV) and Mattress Firm (NASDAQ: MFRM) – just to name a few.

What is the calculus here for such acquisitions? Well in some cases there are genuine synergies associated with combining the two businesses – such as in the case of Microsoft acquiring LinkedIn. In other cases, the calculus is simply as follows: I can borrow at (or near) zero; and the acquired business will likely yield me greater than my borrowing costs. Ipso facto, the deal creates value.

Option (iii) has also been wildly popular for many years now. The calculus is almost the same as above: I can borrow at (or near) zero; and the yield on my stock is greater than my borrowing costs. Ipso facto, the share buy backs make sense.

Believe it or not, even some central banks are making the same calculus and buying stocks or equity ETFs to generate a slightly higher yield on their assets. This is unusual because central bank assets are what effectively “back” the currency of its respective nation. Assets therefore are typically limited to ultra-safe categories – not equities.

So with corporates borrowing to acquire businesses and buy-back stock, it is not surprising that we are seeing a build-up of debt on corporate balance sheets. The data below shows US corporate debt relative to GDP going back around 70 years. It is currently at record levels.

And what is perhaps the most interesting and important segmentation of the data is shown below. This data looks at the build-up in debt on the balance sheets of already-levered corporates over the last five years. The two shades of the same colour delineate between corporates with 6-8x net-debt-to-EBITDA; and >8x net-debt-to-EBITDA. Across nearly all industries, heavily indebted corporates have become significantly more heavily indebted.

Now this is an interesting theme and is not limited to corporates. Heavily-indebted governments have also become even more heavily-indebted over recent years. We can see this clearly in the charts below that illustrate the ratio of public-debt-to-GDP for a handful of large global economies. Across the board (with the recent exception of Germany), government indebtedness has been increasing.

Source: Bloomberg

Similar to in corporate land, the argument for governments goes something like this: as interest rates fall, one’s effective borrowing capacity increases. As interest rates fall, more can be borrowed to result in the same interest expense.

And, of course, many households in certain parts of the world – such as Australia – are making this same calculation. As shown below, note the structural increase household debt as a percentage of disposable income; yet interest paid has actually decreased in recent years as a percentage of disposable income. That is: as interest rates fall, household borrowing capacity increases. And from a mathematical perspective, this argument is valid.

But take this argument to its logical extreme: imagine that all governments, corporates and households increase their borrowings to their newly increased capacities. What might be the result of this behaviour? Well, as borrowings increase, so too would asset values: stocks, bonds and property included. The reason? More money is chasing the same available assets, so asset prices must rise. (This has been the global modus operandi for many years now).

This might sound good – especially if you are currently an owner of stocks, bonds and/or property. But what happens if interest rates start to rise? Naturally, asset prices would likely fall. But perhaps the more important question that we are grappling with is as follows: is it even possible for interest rates to rise? Does the incursion of large levels of debt ensure that rates cannot rise?

To understand why we are even asking such a seemingly absurd question, consider a scenario in which interest rates around the world increase uniformly. What would be the consequences?

Any of the above would likely result in ultra-low interest rates to combat deflation. So either rates stay low; or rates rise and create a set of conditions that force rates lower again. This is the argument. We believe it is worth considering, at the very least.

Indeed, perhaps the only scenario in which rates can increase is a scenario in which inflation expectations remain sustainably elevated. There are probably only two ways this scenario can eventuate: (i) via increased growth expectations from a large and sustained fiscal stimulus – funded by new borrowings; or, even more potent (ii) via increased growth expectations from a large and sustained fiscal stimulus – funded by money printing (known as a Money Financed Fiscal Program – or Helicopter Money).

Either way, any fiscal stimulus that eventuates (if any) will need to be large enough to offset the deflationary consequences of rising interest rates described above. It is not clear that such a fiscal stimulus package is either likely or possible – especially one that is funded by pure money printing.

In the meantime, we would not be surprised if low rates kept edging lower and asset prices kept edging higher. We are in unprecedented financial territory today. Investors need to remain diversified, invested and protected.

This document was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.