|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

-Andrew Macken

We live in dramatic times. A tragic new war has broken out in the Middle East. The war in Ukraine continues. Interest rates keep climbing – the 30-year US Treasury has hit 5%, a level not seen since 2007. And technology – enabled by startling breakthroughs in AI – is changing at near break-neck speed.

Investors are rightly feeling perplexed in deciding what to do with their money and how to position their portfolios.

While no one can predict where markets or individual stocks will head in this environment, there is a surprising amount we can say about the long-term ‘demography’ of stock markets and individual stock returns in general.

Demographics allows us to lift the fog and uncertainty of the short-term, and to see solid and reliable patterns, trends and changes over the long-term that allow us to plan and make good decisions. While it’s impossible to know how tall a child will be when they grow up, we do know that boys will grow to between 160-190cm, 95% of the time. And girls to between 149-174cm, 95% of the time.

Similarly, the stock market has long-term ‘demographic’ characteristics that give investors a ‘probability distribution’ of possible events.

These demographics give investors important context and helpful guardrails to make sensible decisions about their money and portfolios, particularly in these uncertain times.

Here are four important demographic truths of the market.

Equity markets do well in the long term, unambiguously

The first truth is that the stock market is a reliable source of capital growth over the long term.

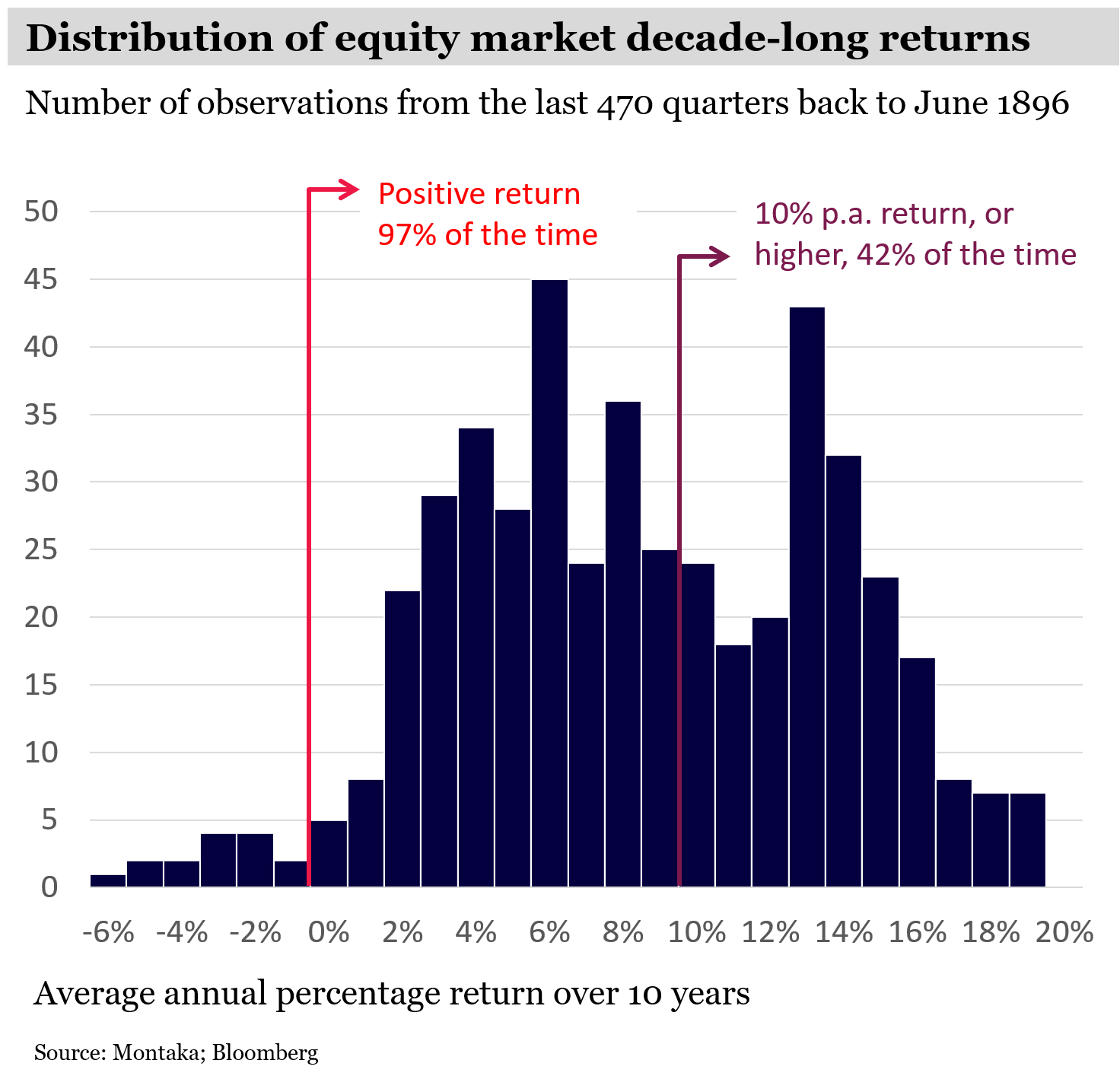

We looked at the Dow Jones Industrial Index’s quarterly returns starting from 1896 to see how frequently the stock market delivered a positive return for investors over a decade.

When held for a period of ten years – and despite war, inflation, periods of 20% interest rates and massive technological disruption – equities delivered a profit 97% of the time.

The overwhelming majority of negative return periods related to the Great Depression, which is now nearly a century ago.

Investors would no doubt like a return greater than just zero over any 10-year period. It turns out that equities delivered investors an average annual return of 10% per annum, or more, 42% of the time. Said another way, investors have more than a 40% chance of increasing their investment by 2.6 times over 10 years. Of course, this return is well above what one could typically expected from bonds or cash over an equivalent period.

The demographic truth is that over the long-run equities are a remarkable wealth builder.

Short-term returns are near-meaningless and should be ignored

The second demographic truth is that, while they will do well in the long term, equities are also frequently declining in the short-term.

From 1896, investors in the Dow Jones Industrial Index would have seen their portfolios decline in value over the previous three months more than one-third of the time.

Investing in individual stocks – even the highest-returning stocks – is no different.

Over the last ten years, from 2013 to today, nearly 60 stocks have delivered a total return of more than 14x over the period. And yet, despite these extraordinary returns, in five months every year, on average, the monthly return of any one of these stocks was negative.

The lesson is that short-term returns – of equity markets, or individual equities –are often best ignored because they bear no relation to long-term returns.

Long-term performance of individual stocks is sometimes extraordinary, and often poor

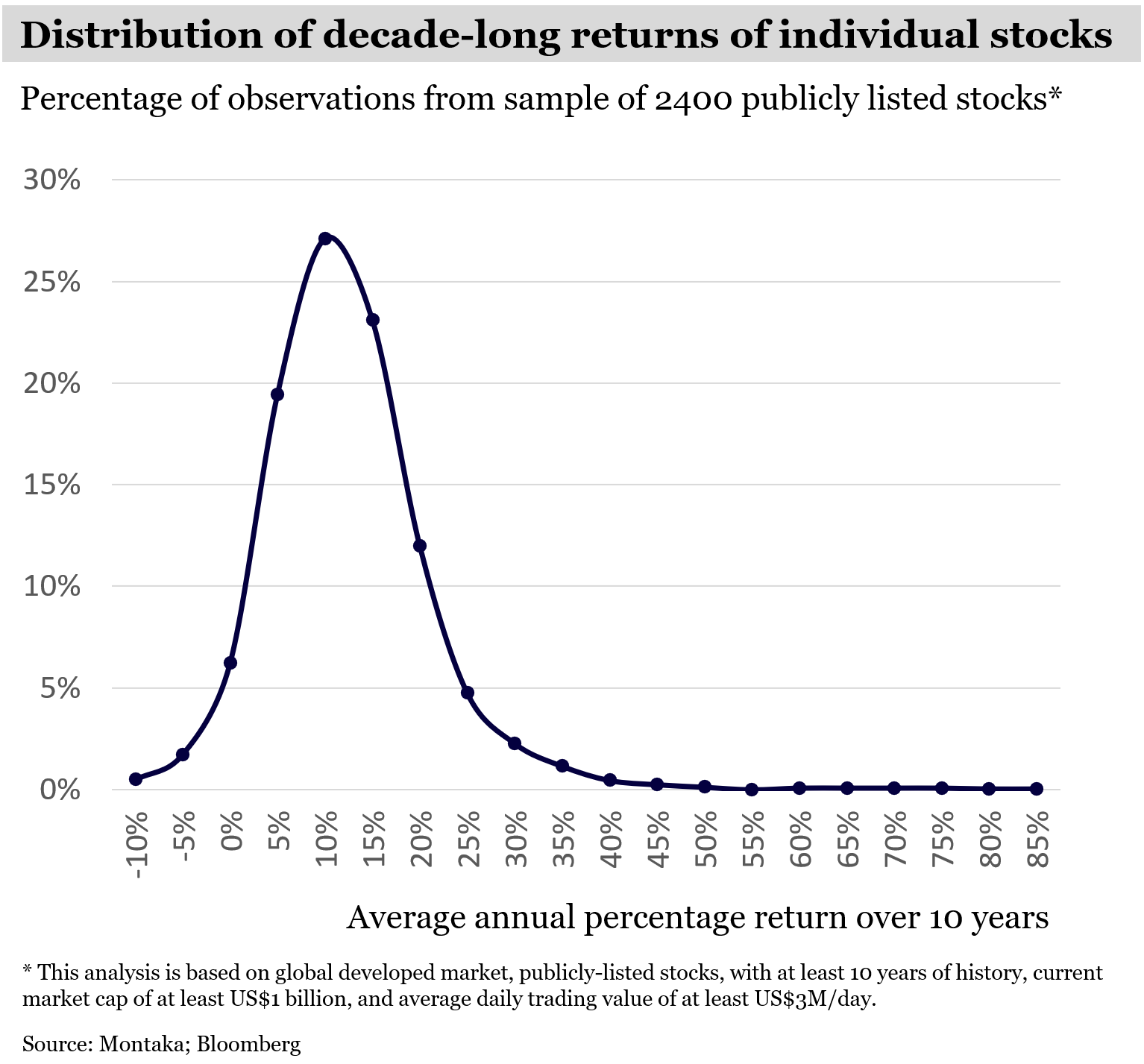

The third demographic truth is that a handful of stocks deliver most of the market’s returns.

For stocks that have been around since 1926, some 60% performed worse than Treasury Bills. (Of the these underperformers, the most frequent outcome was a loss of 100%.)

So how are equity markets so reliable at generating investor returns while, at the same time, individual stocks being so unreliable?

The answer lies in extreme outliers. That is, the small handful of stocks that deliver supernormal returns more than offset the large portion of stocks that deliver poor or negative returns.

The obvious question is: why not simply own the outliers that do extremely well?

The problem is identifying these outliers ahead of time. The odds are heavily stacked against investors trying to do this.

If an investor were to randomly select a publicly listed stock, and own it for 10 years, the probability of that stock being worth 10x or more in a decade is significantly less than 10 percent.

And then, of course, owning an outlier for ten years is no picnic. For outlier stocks that delivered 30% per annum, or more, over the last decade – of which there were 58 stocks in developed global markets – an investor would have spent three years out of ten, on average, in a large draw-down of 30% or more, relative to the prior two-year high watermark.

Equity markets, or equities?

The fourth demographic truth is that, if they do want to outperform, investors must focus their portfolios.

Given the lessons above, particularly the difficulty of identifying outliers, many investors have opted for passive indexation strategies where all stocks are owned in small allocations.

There are valid arguments for such an approach. Investors are nearly guaranteed to own all of the outliers (and own all of the underperformers). And investors are ensured the aggregate average market return – which history tells us nearly always does well over the long term – despite frequent periods of drawdown.

So why don’t all investors adopt such an approach?

Because a purely passive strategy is not an option for investors who want to give themselves a chance of outperforming the market.

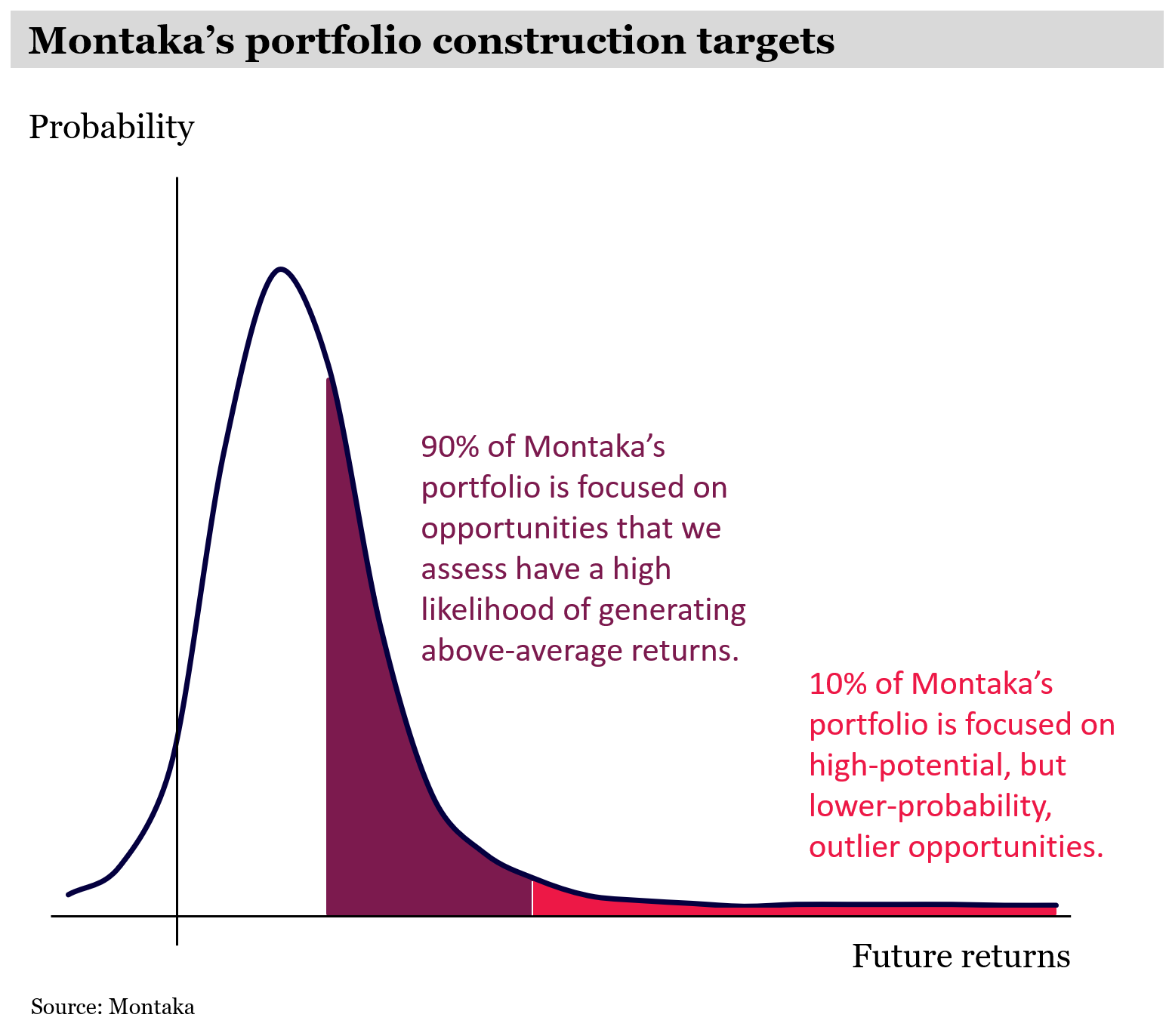

These investors seeking to do better than average will need a process that increases the odds of identifying stocks on the right-hand side of the above distribution.

At Montaka, for example, we have a mandate that requires us to seek better returns than market averages over the long term. Therefore, owning every stock makes no sense for us.

Instead, we screen out stocks that we assess are high probability underperformers. We focus overwhelmingly on stocks that have a high probability of being outperformers – we call these ‘compounders’. And we include a very small allocation to potential outliers where we identify relatively more favorable probabilities of success. Furthermore, we have structured Montaka to have the required ability to own these businesses through frequent periods of drawdown.

There is no doubt the current environment is febrile and uncertain. It is a challenging time for investors. But it pays for investors to take a longer view, to step back and look at the long-term ‘demographic’ truths of the market. Those truths reveal that investors should ignore short-term noise and be patient, have faith in equities, and – if they are seeking to outperform the market – focus on high-potential stocks that will deliver superior returns over the long run.

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stockpicks. Click below to listen. Alternatively, click on this link: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/montaka

To request a copy of our latest paper which explores the empirical research around the 3 pillars of active management outperformance, please share your details with us:

Note: Montaka is invested in Spotify, Microsoft, Amazon and Blackstone.

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments.

To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100 or leave us a line on montaka.com/contact-us