|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The disappointing public market debuts of private market darlings Uber and Lyft, and the nervous handwringing of their unicorn compatriots waiting in the pipeline (WeWork, Airbnb, Slack to name a few), serve as another reminder to investors of the importance of sound financial analysis using financial metrics that bear some semblance to reality.

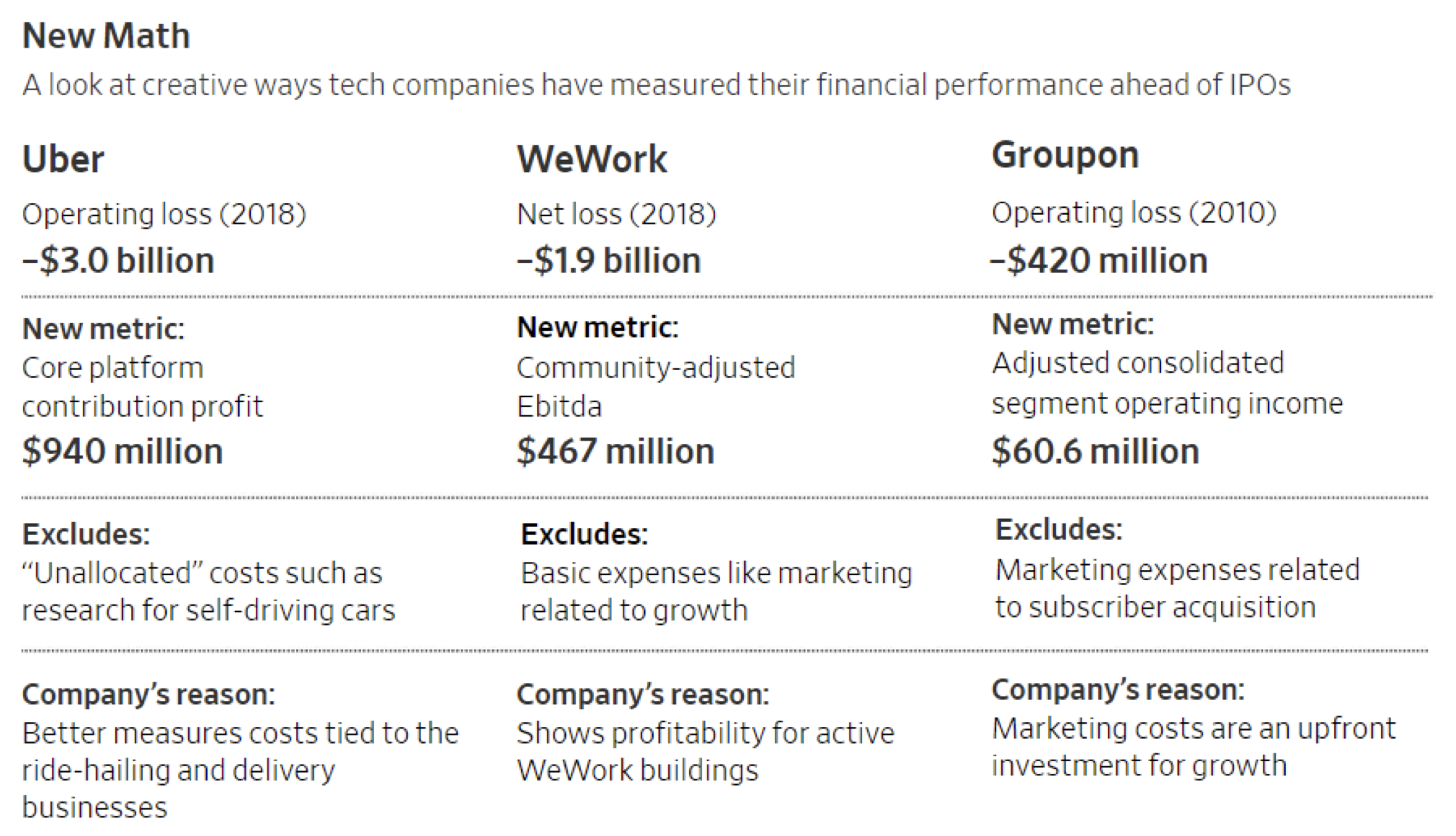

In order to convince public market investors of their dazzling private market valuations, these rapidly growing but loss-making companies and their backers have invented creative if not wholly fanciful measures for evaluating their performance. These alternative or “adjusted” measures are nothing new – indeed many public companies provide adjusted earnings to normalise for what management consider to be extraordinary or non-recurring items – but the extent of the adjustments proposed by the companies in question are so far removed from economic reality as to be entirely useless to a prudent investor.

Source: The Wall Street Journal, company filings

Take Uber for instance. The company’s S-1 discloses a GAAP operating loss of $3.0 billion in 2018, yet through the magic of adjustments it also achieved a “core platform contribution profit” of $940 million. Among the items excluded from core platform contribution profit are $0.5 billion of R&D expenses related to Uber’s future (mainly autonomous driving), $2.1 billion of other unallocated R&D and general & administrative expenses related to non-core functions such as finance, accounting, tax and IT, $0.4 billion of D&A, and a $152 million loss related to “Other Bets”. These adjustments supposedly give investors a better idea of the direct costs and profitability of the core ride-sharing and Uber Eats businesses, but of course investors are not just buying into the core platform.

Uber’s competitor Lyft is no better with its adjustments that turned a 2018 GAAP operating loss of $978 million into a rosy “contribution” of $921 million. From page 84 of its S-1 filing: “We define Contribution as revenue less cost of revenue, adjusted to exclude [several minor] items from cost of revenue.” To a normal investor, that would be defined as gross profit.

WeWork’s “community adjusted EBITDA” is perhaps even more controversial. The name suggests some measure of adjusted earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation, but also excludes sales & marketing expenses, growth & new market development expenses, general & administrative expenses, pre-opening expenses and hefty stock-based compensation amongst other items. It even adjusts for the “impact of straight-lining of rent” which must be an inconvenient GAAP requirement. “Community adjusted EBITDA” is intended to indicate the profitability of mature WeWork buildings that are tenanted and omits the cost of growth and the customer acquisition costs.

To be clear, this post is not condemning the use of non-GAAP performance measures generally. There are many legitimate occasions where excluding items such as impairments, one-off legal costs or restructuring costs (within reason) gives investors a better picture of the underlying performance of a company. But to exclude operating costs related to customer acquisition or future growth because they depress the “current” profitability of the business absolutely deviates from economic reality – especially in highly competitive industries where ongoing marketing and R&D costs are necessary to remain relevant.

One potential explanation for these increasingly aggressive non-GAAP performance measures is that many of these highly valued private companies have grown themselves into a corner by remaining private for so long. Public investors can be understanding of young companies that go to market while still loss-making, but only if there’s still an opportunity to make an attractive return. Many of the current crop of unicorns are approaching or past their 10-year anniversaries and still incurring historic GAAP losses even as their top lines decelerate, and have been valued by private investors on a “greater fool” basis. It appears that this time, public investors are reluctant to play the role of the greater fool.

![]() Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.