|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

-Andrew Macken

Concentration within US equity markets has surged.

Now at multi-decade highs, the ten largest stocks – most of which are the mega-tech companies – account for 33% of the S&P 500 market cap, according to Goldman Sachs.[1]

By comparison, at the height of the 2000 dot com bubble, concentration only reached 27%.

The current concentration is raising investor fears. At best, could it signal impending underperformance by the world’s mega tech companies? At the very worst, could it portend a destructive stock market bubble bust?

S&P 500 Concentration – By value

Source: Goldman Sachs

But despite those concerns, investors should not be fearing today’s high levels of stock market concentration.

They reflect an increasing contribution by the tech sector to the real economy, as well as increasing concentration within the tech sector itself. And with the drivers of this concentration only gathering speed, investors should expect a higher level of stock market concentration in the future relative to what we’ve seen over recent decades.

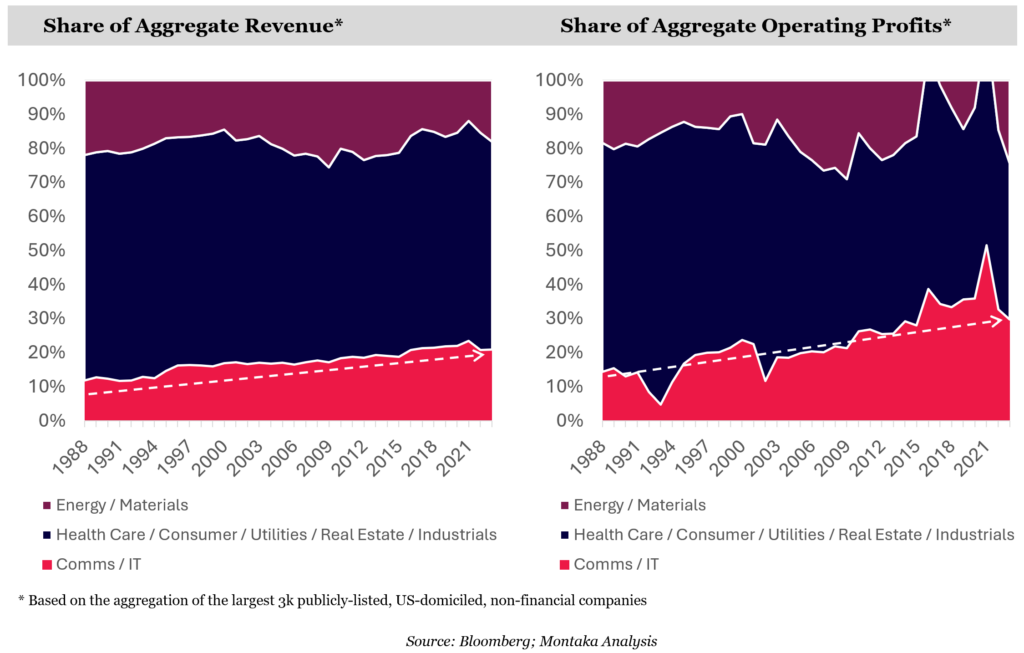

The tech sector’s contribution to the real economy is structurally increasing

Over nearly four decades, the tech sector has grown its revenues more rapidly than other sectors, resulting in a steady, structural increase in contribution to the real economy. Blessed with above-average profit margins, the tech sector’s share of corporate profits has been increasing at an even faster rate.

The major driver of these trends is the increasing proliferation of technology in all walks of life.

Remember that access to computing was extremely sparse prior to the 1990s. In 1977, for example, Apple sold 600 machines in total. In the 1980s, thanks to the IBM PC platform, personal computers proliferated, with as many as 16 million units sold annually. By the end of the 1990s, annual PC shipments were nearly 10x this level.[2]

Around the same time, the internet started to gather momentum. In 1995, fewer than 15% of American adults used the internet. Just five years later this ratio was almost at 50%, and by 2010 nearly 80%.[3]

Then in 2007, Steve Jobs revealed the first version of the iPhone – sparking a smartphone revolution. Today, there are more connected smartphones in the world than there are people.

All of these were distinct and transformational waves of tech proliferation into more far-reaching parts of the global economy thanks to structurally increasing computing power at rapidly declining costs.

The tech sector itself is becoming more concentrated

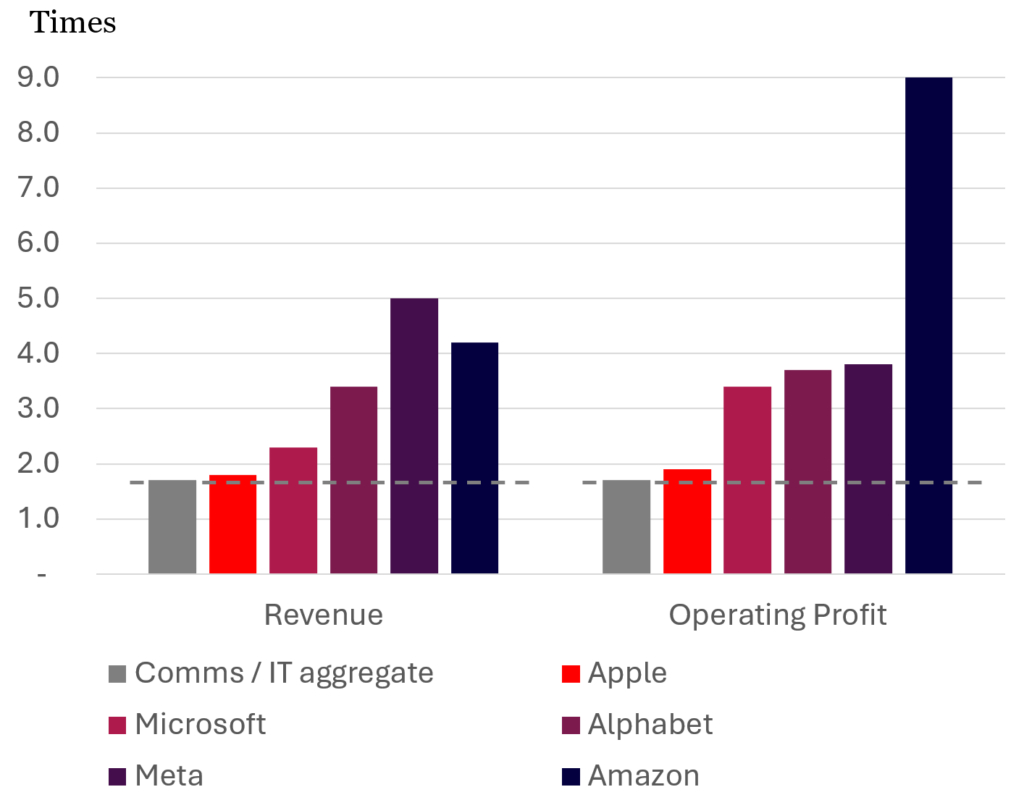

Within the tech sector, the largest companies also tend to grow their revenues and earnings at higher-than-the-average rates. They therefore gain an increasing share of the overall sector. That is, the tech sector itself is becoming more concentrated.

For example, the aggregate Communications and IT sector increased both revenues and earnings by 1.7x over the last seven years. But the industry’s largest companies – including Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft and Apple – generated even bigger increases over the same period.

7 Year Growth to 2023

Source: Bloomberg; Montaka Analysis

Not only are we seeing a structural increase in the tech sector’s contribution to the real economy, but we also clearly see a structural increase in the domination by the mega tech companies within the sector itself.

The drivers of tech concentration appear to be gathering steam

Today’s mega techs are not like most companies that procure inputs, add value, and sell a good or a service to customers. They are mission-critical platforms upon which large and increasing swathes of the economy are built.

And these platforms have positive network effects: the larger they become, the more useful their offerings are to customers, and their advantages over the competition grow stronger.

Nearly every company and government in the western world has some of its IT systems reliant on Amazon Web Services (AWS), or Microsoft Azure, for example. And nearly every business – small, medium, and large – spends marketing dollars on Meta and Google to generate revenues.

Today’s mega techs enjoy enormous scale advantages that are near-impossible for competitors to match. This year, four companies alone (all of which are in the top six largest companies in the S&P 500) will spend in the order of US$160 billion in capital investments. This is in addition to R&D spend of around the same amount again. These investments create new offerings that can be leveraged by global customers at much lower unit cost than any subscale competitor could achieve.

The infusion of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into software – a major transformation which is starting to accelerate and remains in its infancy – will likely strengthen existing scale advantages. The nature of AI means the usefulness and differentiation of its use-cases are largely determined by the size and quality of datasets used to train, fine-tune and integrate with AI models. These datasets overwhelmingly belong to today’s existing leaders – in substantially all industries. (Interestingly, this dynamic points to growing corporate inequality in all sectors going forward, in addition to the tech sector.)

Last year, the founder of marketing software provider HubSpot, Brian Halligan, spoke about the massive data advantages of incumbents in the age of AI. He said that, while the rebels typically have the advantage over incumbents in most disruptions, AI is a rare case where the reverse is true … because of the need for data. The incumbents, Halligan said, have built up so much data over so many years, and are moving so quickly with AI, that any new rebel competitor simply cannot compete. And he added that it is very difficult to get the data that you need to compete, if you don’t already have it.[4]

… And this points to higher stock market concentration

Stock market valuations reflect aggregate expectations about the future. The evidence points to even higher concentration within the real economy, dominated by the world’s mega tech companies.

It follows, therefore, that stock market concentration may very well go higher, as counterintuitive as that may feel.

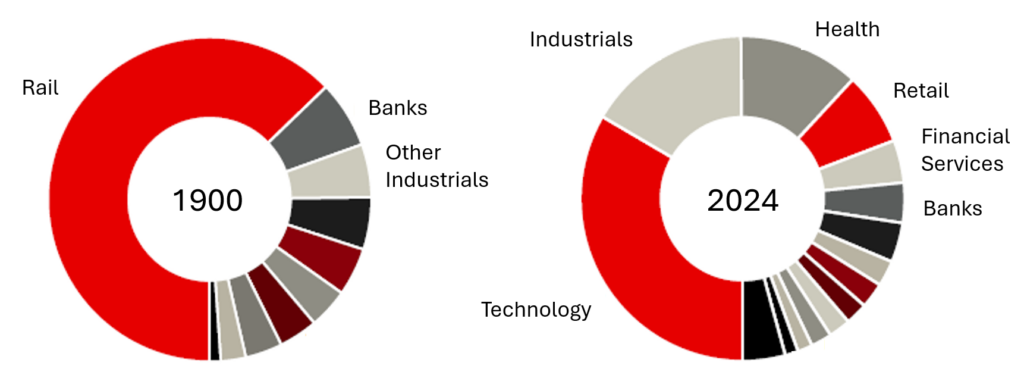

Interestingly, higher concentration is not unprecedented. More than 120 years ago, rail companies accounted for approximately two-thirds of the value of US stock markets, following the country’s industrial boom and industry consolidation, influenced by the likes of J. P. Morgan.

Of course, what followed was World War I, a complete nationalization of US railroads, and a Great Depression. So we hope the historical precedent does not extend too far.

US Public Equity Markets – By Sector: 1900 vs 2024

Source: Bloomberg (February, 2024)

* * *

Investors are right to raise an eyebrow to elevated levels of stock market concentration. This is something that has historically reverted to the mean. And investors rightly want to avoid the potential for periods of underperformance or downright collapse in the world’s largest publicly listed companies.

But the nature of this concentration reflects something more structural in the real economy. The proliferation of tech into the broader economy continues structurally. And the world’s most advantaged tech platforms, with positive network effects, continue to grow even larger and extend their advantages over the competition. The nature of AI looks like it will only increase corporate inequality and boost concentration levels further.

If only because today’s stock market concentration stems from the mega tech platforms – and reflects the underlying concentration taking place in the real economy, one’s fears of a substantial misallocation of market value can be allayed.

Note:

[1] Goldman Sachs: 100 years of US equity market concentration and momentum (March 2024)

[2] Arstechnica: Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures (2005)

[3] Pew Research Center

[4] Podcast: No Priors (October 2023)

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stockpicks. Click below to listen. Alternatively, click on this link: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/montaka

To request a copy of our latest paper which explores the empirical research around the 3 pillars of active management outperformance, please share your details with us:

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments.

To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100 or leave us a line on montaka.com/contact-us