By Andrew Macken

In late January, from his office in Paris, Bernard Arnault, one of the world’s richest men and Chairman and CEO of luxury giant, LVMH, told investors that he had just returned from Trump’s Presidential Inauguration and seen optimism returning to the United States.

“In the US, people are welcoming you with open arms. Taxes are going down to 15%… You come back to France … it is extremely elitist … taxes are going up to 40% … That’s a good way to tame your enthusiasm.”[1]

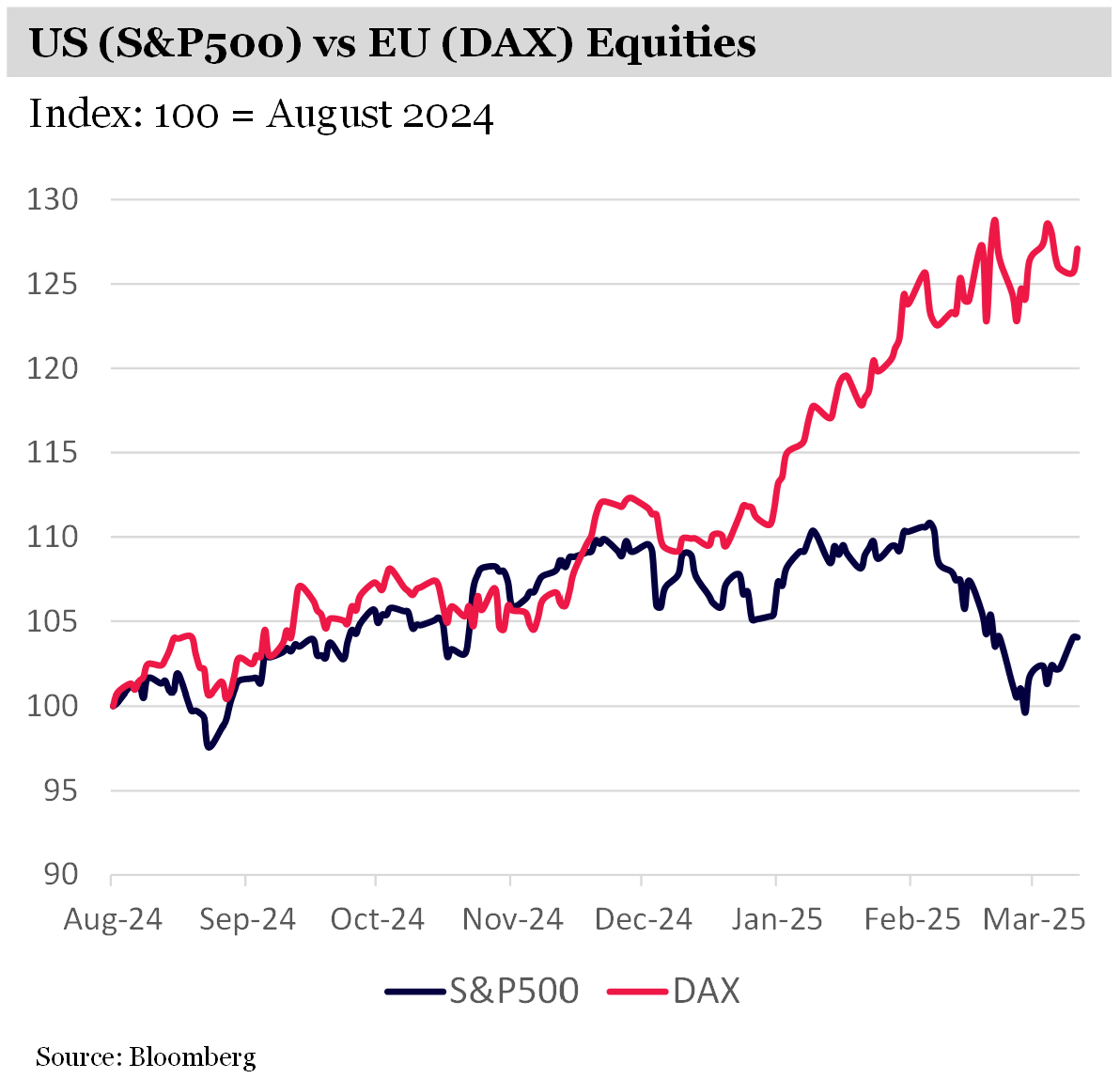

US equities were booming, reflecting this Trump-fueled enthusiasm.

Then it all changed.

US equities collapsed as the Trump Administration unleashed its unique brand of unpredictable politics. Trump sporadically announced tariffs, then backtracked, then forward tracked. The President flipped geopolitical alliances on their head – he loosely threatened Canada with annexation, while the US voted with Russia at the UN General Assembly, and against Europe, for the first time in 80 years.

Meanwhile, equities in Europe were booming – especially in Germany. In the narrow 30 day window between the German election and the final day of the existing German parliament’s term, an enormous fiscal spending bill was approved.

Motivated by new security concerns following Trump’s threats to revoke security guarantees, the German parliament approved the carve-out of defense and security expenditures from the country’s ‘debt break’ in addition to a new stand-alone €500 billion infrastructure and climate fund to make investments over the next 12 years.

France and Italy also have ambitions to increase defense spending.

Is this the beginning of a new sustained rally in European equities?

In the short-to-medium term, the enormous fiscal spending out of Germany is surely a positive tailwind. But over the longer-term, economic fundamentals will drive destinies. And the fundamentals of Europe remain concerning.

In the note below, we examine five reasons why Europe’s stock rally may not live up to expectations.

-

Economic gravity will likely hinder European stocks over time

The economic news in Europe is largely focused on a new, large-scale fiscal spending program motivated by national defense concerns. Such spending should increase aggregate demand over the short-to-medium term, which will boost the revenues and earnings of many European businesses. In anticipation, investors have started to bid up the prices of European equities.

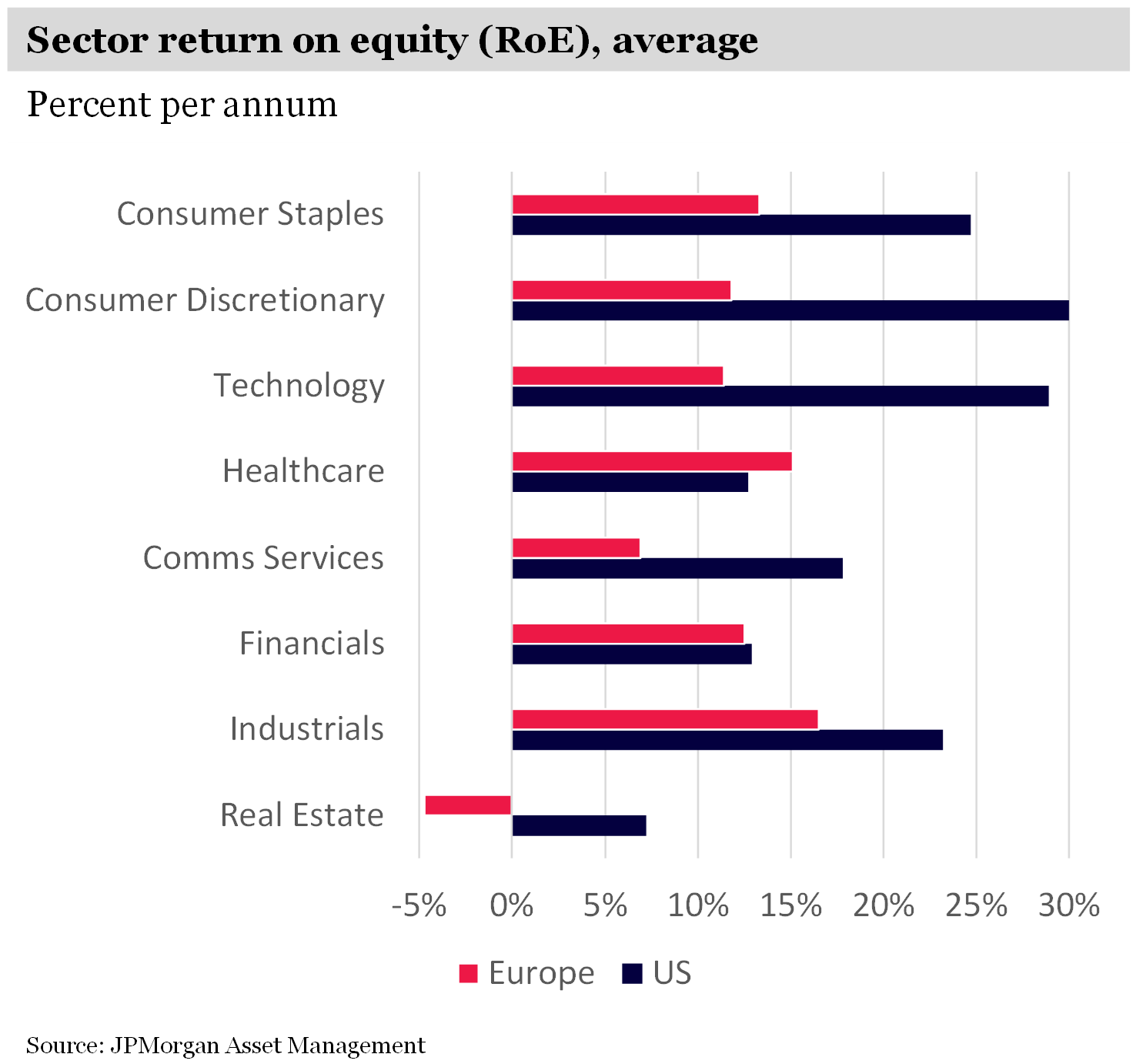

But over time, what matters for stock prices are the profits that businesses can generate relative to their invested capital. If too much capital is required to generate profits, then stock prices can fall (or at least not increase by much) – even for businesses with growing earnings power.

As shown in the chart below, when it comes to return on equity (ROE), European businesses have lagged, especially compared to their counterparts in the US. Europe’s meagre returns on invested equity stem from competitive disadvantages – many of which emanate from the EU’s well-meaning, though unintentionally cumbersome, policies.

If European companies cannot meet their growing demand with higher ROEs over time, then this fiscal opportunity will be squandered and shareholders will pay the price.

-

Regulatory burdens are a major competitive disadvantage for European businesses

One of the major competitive disadvantages for European firms, of course, is overregulation.

When online payments platform Stripe released its annual letter recently, they shared a survey response from a German entrepreneur who lamented that setting up a corporate structure in Germany takes 2-3 months. The burden of physical signatures adds additional time to raise money from angel investors. Yet a company can be set up in the US, and capital raised via electronic signatures, within a few days.[2]

This inefficiency is an “existential challenge” wrote former ECB President, Mario Draghi, in his scathing report, The future of European Competitiveness, published in September 2024.

More than 60% of EU companies see regulation as an obstacle to investment, with 55% of SMEs flagging regulatory obstacles and the administrative burden as their greatest challenge.[3]

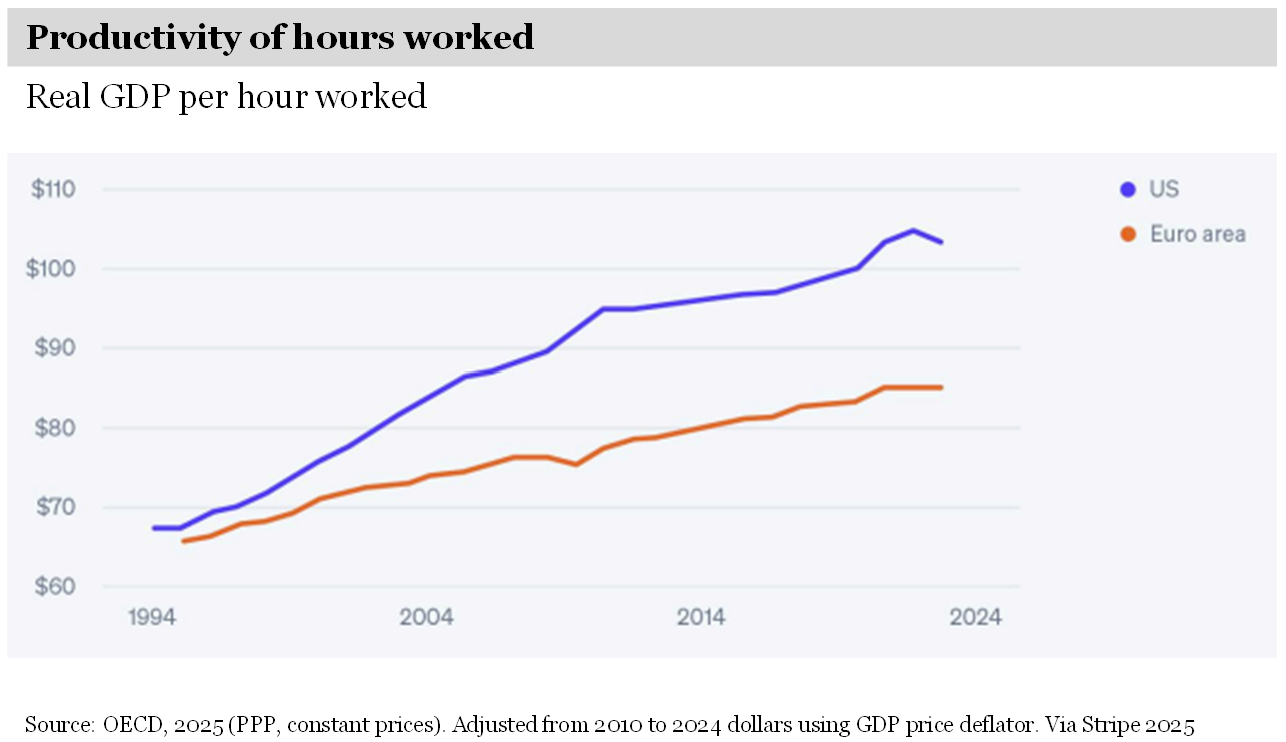

As illustrated below, the productivity of each hour worked by a European employee is now substantially below that of an American employee.

Over the course of the last 10-15 years, even capital investments made by businesses – once superior – has now fallen below US levels (as a percent of GDP). Investment is not only a source of near-term demand, but it can also unlock longer-term productivity gains.

While the Europeans grapple with how to address these shortcomings, the new Trump Administration is preparing to ‘tear up’ the regulatory rule book Stateside. After speaking with multiple experts, we expect substantial deregulation in the US in the near term – particularly in the financial sectors.

-

Demographics in Europe are going from bad to worse

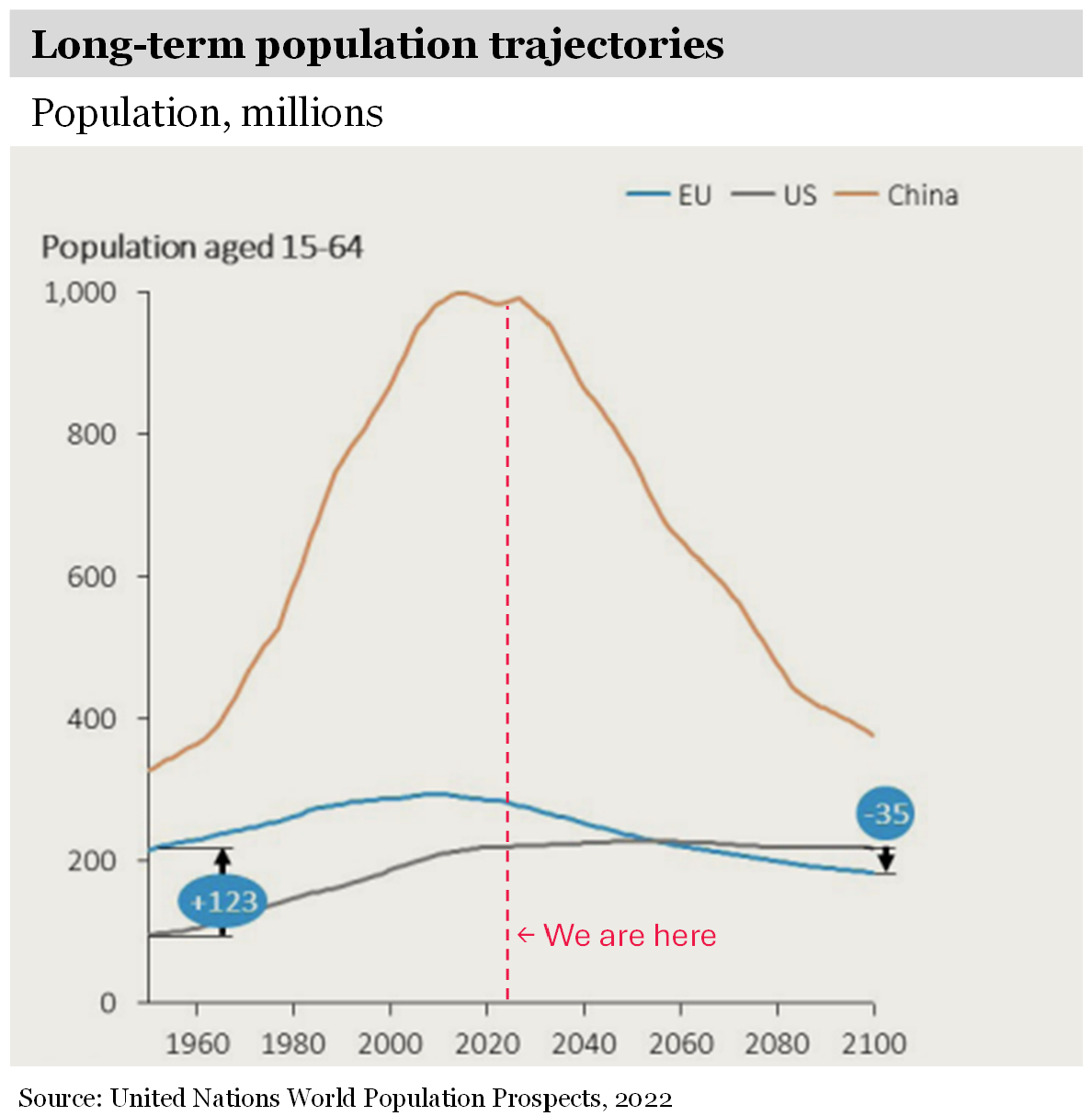

While slow moving, demographics – especially the 15 to 64-year-old working-age cohort – are arguably one of the most important structural drivers of economic growth. Yet the EU, along with China, is entering the first period in its recent history where growth will not be supported by rising populations. The US, however, is not.

Without a major uptick in productivity, European economic growth is set to stall. And along with unsustainable and historically high (and set to increase) public debt-to-GDP ratios, Europe may be forced to make painful cuts to living standards over time.

Japan offers a notable case study of the possible fate that awaits Europe. Since its working-age population started to shrink in the mid-1990s, Japan’s real GDP growth has averaged less than 1% per annum; and public debt-to-GDP has increased from approximately 70% to more than 250%.[4]

(For reference, Germany’s public debt-to-GDP is approximately 62% – relatively low by European standards and reflects genuine fiscal space to borrow. France’s of 110%, and Italy’s of 138%, on the other hand, represent more substantial risks of longer-term debt unsustainability).[5]

-

National security may have just flipped to national insecurity

It goes without saying that national security is one of those invisible things that contribute to the value of equity investments. Take it away and equity impairments can become real and substantial.

On election night in February, Germany’s new chancellor-in-waiting, Friedrich Merz, made an unprecedented statement following President Trump’s threats to revoke European security guarantees in place since 1945: “It is clear that this government [i.e. Trump’s] does not care much about the fate of Europe.”

Since then, Germans – and many other European member states – have been scrambling to effect new, large-scale debt-financed fiscal packages aimed at dramatically boosting Europe’s defenses.

Security fears are real. It’s not just a question of whether Trump will leave in place US security guarantees. It’s a question, now based on recent events, of whether or not those guarantees can even be trusted.

In a recent Montaka interview with a Berlin-based political advisor, we learnt that Germans are very concerned. “Pandoras box has now been opened.” The advisor even wondered if Trump might consider changing sides (to support Putin’s Russia) completely.

For equity investors, large-scale debt-financed fiscal stimulus certainly represents a powerful boost to short-term stock prices. But it also accelerates the buildup of public-debt-GDP ratios and increases the risks of debt unsustainability – a headwind that Europe is set to face already, as former ECB President Draghi pointed out last year.

And, of course, an attack on Europe while defenses are weak, though very unlikely, would surely be negative for stock prices – especially in the country in which the conflict was being fought.

-

European politics continue to fragment, raising the risk of EU dissolution

To the extent the US is no longer a reliable partner to Europe, the one ‘positive’ to emerge is a new acceptance among most member states and politicians that they need to cooperate. Through this lens, the union is being strengthened today.

But underneath the surface, the political trends across Europe are undoubtedly moving away from European unity.

Most far-right parties in Europe are nationalistic, anti-immigrant, and Eurosceptic. By mid-2027, there is a good chance that the second and third largest countries in Europe (France and Italy) will both be led by their respective far-right party leaders, Marine Le Pen (subject to the outcome of her recent embezzlement conviction [6]) and Giorgia Meloni.

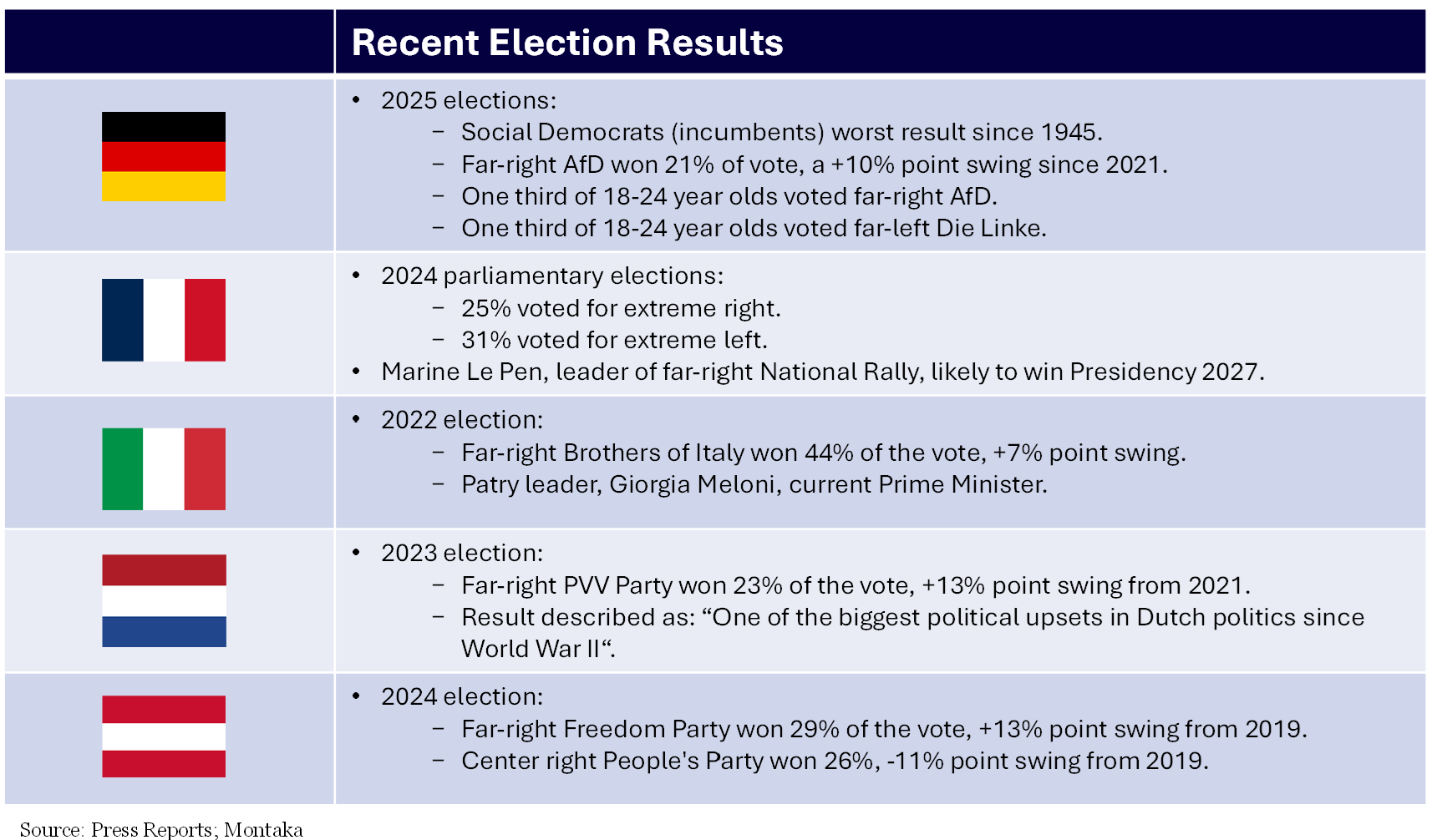

The table below provides a snapshot of key election results across the EU over the last three years. The rise of the far-right is clearly observable (as is the rise of the far-left in some countries, pointing to increasing political polarization).

From a financial perspective, a dissolution of the monetary union would likely be a turbulent event. European banks and insurance companies represent large, levered owners of the sovereign bonds issued by member states. If one member were to leave the monetary union, for example, and its outstanding bonds required a write-down, this could lead to large-scale equity impairments for the owners of these bonds.

Today this remains a low probability scenario. But the political winds are slowly increasing the likelihood that we will end up here one day.

Misplaced optimism?

The recent rally in European equities warrants careful consideration. While fiscal stimulus represents a substantial short-to-medium term boost, fundamental challenges threaten the long-term health and stability of European markets.

These challenges are multifaceted and include structural competitive disadvantages that hinder returns on capital investment; complex regulatory burdens that erode productivity; demographic headwinds; national security risks; and political fragmentation that is emboldening far-right, Eurosceptic parties.

Collectively, these factors suggest that the current market optimism may be misplaced – especially when viewed through a longer-term prism.

Note:

[1] (LVMH) FY24 Earnings Call, January 2025

[2] (Stripe) 2024 Annual Letter, February 2025

[3] The future of European Competitiveness, September 2024

[4] (Montaka) Low rates, assets inflate, November 2019

[5] Based on data provided by CEIC.

[6] (Reuters) France’s Le Pen convicted of graft, barred from running for president in 2027, March 2025

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100 or leave us a line at montaka.com/contact-us

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.

5 reasons why Europe’s stock rally may not live up to expectations

By Andrew Macken

In late January, from his office in Paris, Bernard Arnault, one of the world’s richest men and Chairman and CEO of luxury giant, LVMH, told investors that he had just returned from Trump’s Presidential Inauguration and seen optimism returning to the United States.

“In the US, people are welcoming you with open arms. Taxes are going down to 15%… You come back to France … it is extremely elitist … taxes are going up to 40% … That’s a good way to tame your enthusiasm.”[1]

US equities were booming, reflecting this Trump-fueled enthusiasm.

Then it all changed.

US equities collapsed as the Trump Administration unleashed its unique brand of unpredictable politics. Trump sporadically announced tariffs, then backtracked, then forward tracked. The President flipped geopolitical alliances on their head – he loosely threatened Canada with annexation, while the US voted with Russia at the UN General Assembly, and against Europe, for the first time in 80 years.

Meanwhile, equities in Europe were booming – especially in Germany. In the narrow 30 day window between the German election and the final day of the existing German parliament’s term, an enormous fiscal spending bill was approved.

Motivated by new security concerns following Trump’s threats to revoke security guarantees, the German parliament approved the carve-out of defense and security expenditures from the country’s ‘debt break’ in addition to a new stand-alone €500 billion infrastructure and climate fund to make investments over the next 12 years.

France and Italy also have ambitions to increase defense spending.

Is this the beginning of a new sustained rally in European equities?

In the short-to-medium term, the enormous fiscal spending out of Germany is surely a positive tailwind. But over the longer-term, economic fundamentals will drive destinies. And the fundamentals of Europe remain concerning.

In the note below, we examine five reasons why Europe’s stock rally may not live up to expectations.

Economic gravity will likely hinder European stocks over time

The economic news in Europe is largely focused on a new, large-scale fiscal spending program motivated by national defense concerns. Such spending should increase aggregate demand over the short-to-medium term, which will boost the revenues and earnings of many European businesses. In anticipation, investors have started to bid up the prices of European equities.

But over time, what matters for stock prices are the profits that businesses can generate relative to their invested capital. If too much capital is required to generate profits, then stock prices can fall (or at least not increase by much) – even for businesses with growing earnings power.

As shown in the chart below, when it comes to return on equity (ROE), European businesses have lagged, especially compared to their counterparts in the US. Europe’s meagre returns on invested equity stem from competitive disadvantages – many of which emanate from the EU’s well-meaning, though unintentionally cumbersome, policies.

If European companies cannot meet their growing demand with higher ROEs over time, then this fiscal opportunity will be squandered and shareholders will pay the price.

Regulatory burdens are a major competitive disadvantage for European businesses

One of the major competitive disadvantages for European firms, of course, is overregulation.

When online payments platform Stripe released its annual letter recently, they shared a survey response from a German entrepreneur who lamented that setting up a corporate structure in Germany takes 2-3 months. The burden of physical signatures adds additional time to raise money from angel investors. Yet a company can be set up in the US, and capital raised via electronic signatures, within a few days.[2]

This inefficiency is an “existential challenge” wrote former ECB President, Mario Draghi, in his scathing report, The future of European Competitiveness, published in September 2024.

More than 60% of EU companies see regulation as an obstacle to investment, with 55% of SMEs flagging regulatory obstacles and the administrative burden as their greatest challenge.[3]

As illustrated below, the productivity of each hour worked by a European employee is now substantially below that of an American employee.

Over the course of the last 10-15 years, even capital investments made by businesses – once superior – has now fallen below US levels (as a percent of GDP). Investment is not only a source of near-term demand, but it can also unlock longer-term productivity gains.

While the Europeans grapple with how to address these shortcomings, the new Trump Administration is preparing to ‘tear up’ the regulatory rule book Stateside. After speaking with multiple experts, we expect substantial deregulation in the US in the near term – particularly in the financial sectors.

Demographics in Europe are going from bad to worse

While slow moving, demographics – especially the 15 to 64-year-old working-age cohort – are arguably one of the most important structural drivers of economic growth. Yet the EU, along with China, is entering the first period in its recent history where growth will not be supported by rising populations. The US, however, is not.

Without a major uptick in productivity, European economic growth is set to stall. And along with unsustainable and historically high (and set to increase) public debt-to-GDP ratios, Europe may be forced to make painful cuts to living standards over time.

Japan offers a notable case study of the possible fate that awaits Europe. Since its working-age population started to shrink in the mid-1990s, Japan’s real GDP growth has averaged less than 1% per annum; and public debt-to-GDP has increased from approximately 70% to more than 250%.[4]

(For reference, Germany’s public debt-to-GDP is approximately 62% – relatively low by European standards and reflects genuine fiscal space to borrow. France’s of 110%, and Italy’s of 138%, on the other hand, represent more substantial risks of longer-term debt unsustainability).[5]

National security may have just flipped to national insecurity

It goes without saying that national security is one of those invisible things that contribute to the value of equity investments. Take it away and equity impairments can become real and substantial.

On election night in February, Germany’s new chancellor-in-waiting, Friedrich Merz, made an unprecedented statement following President Trump’s threats to revoke European security guarantees in place since 1945: “It is clear that this government [i.e. Trump’s] does not care much about the fate of Europe.”

Since then, Germans – and many other European member states – have been scrambling to effect new, large-scale debt-financed fiscal packages aimed at dramatically boosting Europe’s defenses.

Security fears are real. It’s not just a question of whether Trump will leave in place US security guarantees. It’s a question, now based on recent events, of whether or not those guarantees can even be trusted.

In a recent Montaka interview with a Berlin-based political advisor, we learnt that Germans are very concerned. “Pandoras box has now been opened.” The advisor even wondered if Trump might consider changing sides (to support Putin’s Russia) completely.

For equity investors, large-scale debt-financed fiscal stimulus certainly represents a powerful boost to short-term stock prices. But it also accelerates the buildup of public-debt-GDP ratios and increases the risks of debt unsustainability – a headwind that Europe is set to face already, as former ECB President Draghi pointed out last year.

And, of course, an attack on Europe while defenses are weak, though very unlikely, would surely be negative for stock prices – especially in the country in which the conflict was being fought.

European politics continue to fragment, raising the risk of EU dissolution

To the extent the US is no longer a reliable partner to Europe, the one ‘positive’ to emerge is a new acceptance among most member states and politicians that they need to cooperate. Through this lens, the union is being strengthened today.

But underneath the surface, the political trends across Europe are undoubtedly moving away from European unity.

Most far-right parties in Europe are nationalistic, anti-immigrant, and Eurosceptic. By mid-2027, there is a good chance that the second and third largest countries in Europe (France and Italy) will both be led by their respective far-right party leaders, Marine Le Pen (subject to the outcome of her recent embezzlement conviction [6]) and Giorgia Meloni.

The table below provides a snapshot of key election results across the EU over the last three years. The rise of the far-right is clearly observable (as is the rise of the far-left in some countries, pointing to increasing political polarization).

From a financial perspective, a dissolution of the monetary union would likely be a turbulent event. European banks and insurance companies represent large, levered owners of the sovereign bonds issued by member states. If one member were to leave the monetary union, for example, and its outstanding bonds required a write-down, this could lead to large-scale equity impairments for the owners of these bonds.

Today this remains a low probability scenario. But the political winds are slowly increasing the likelihood that we will end up here one day.

Misplaced optimism?

The recent rally in European equities warrants careful consideration. While fiscal stimulus represents a substantial short-to-medium term boost, fundamental challenges threaten the long-term health and stability of European markets.

These challenges are multifaceted and include structural competitive disadvantages that hinder returns on capital investment; complex regulatory burdens that erode productivity; demographic headwinds; national security risks; and political fragmentation that is emboldening far-right, Eurosceptic parties.

Collectively, these factors suggest that the current market optimism may be misplaced – especially when viewed through a longer-term prism.

Note:

[1] (LVMH) FY24 Earnings Call, January 2025

[2] (Stripe) 2024 Annual Letter, February 2025

[3] The future of European Competitiveness, September 2024

[4] (Montaka) Low rates, assets inflate, November 2019

[5] Based on data provided by CEIC.

[6] (Reuters) France’s Le Pen convicted of graft, barred from running for president in 2027, March 2025

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.This content was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.