|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

-Amit Nath

Many of the world’s best-known and most valuable businesses operate a ‘platform’ business model. Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft and Meta are all variations of platforms that allow them to dominate and create immense value in their chosen verticals.

But not all platforms are created equal, and not all businesses that claim to be platforms are.

The term ‘platform’ has unfortunately evolved into a buzzword used freely by marketing departments and promotional management teams hoping to attract a platform valuation for a linear business.

Rather than a platform, investors can find themselves standing on a trapdoor: a fake platform business with a high probability of failure like Peloton and Zoom. If you mistake one for the other, it can mean the difference between the bottom falling out of your investment and summiting a mountain of gold.

Source: Image Creator (Bing), Montaka.

The traditional ‘linear’ business

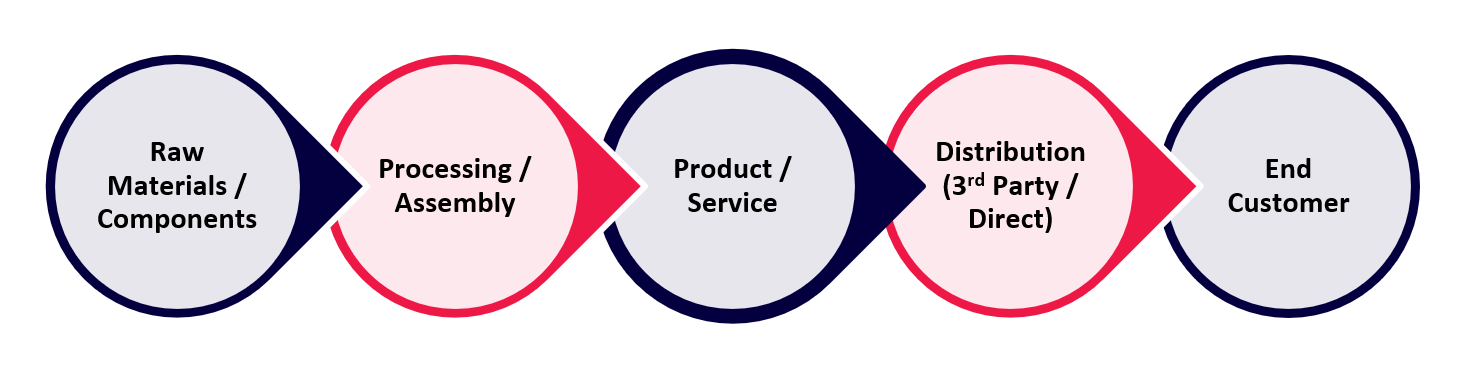

Linear, or traditional business models are the economy’s most common. They acquire raw materials or components and process or assemble them to create a product which is sold to a customer (either directly or through a distributor).

Linear businesses create value internally then sell that value downstream to customers. As you can see below, value flows from left to right, from raw materials to customers, with each intermediary step taking a clip along the way and introducing several points of failure and potential for disintermediation.

Linear Businesses

Source: Montaka

Source: Montaka

For much of the twentieth century, linear businesses sourced their competitive advantage from their supply chain and distribution networks. They optimized internal systems and processes, which led to lower unit costs, better prices for customers, higher market share, and more profit for themselves.

Companies such as Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Nestle and PepsiCo all benefited from these strategies, and ultimately consolidated their industries to become scale market leaders.

The model has some weaknesses, however. It relies on third parties for distribution (e.g. grocery stores and restaurants). It often sterilizes manufacturers and brand owners from their customer base, so they do not get the benefit of direct relationships and access to the extremely valuable data this generates.

Many linear businesses are classic product companies (packaged food, furniture, refrigerators). They can also be service businesses with skilled workers (tax advisors, hairdressers, nail salons). These types of businesses generally grow by adding staff, physical assets, or both.

This dynamic reveals their biggest weakness: resource intensive growth. Linear businesses do not tend to scale well beyond a certain point and hit a ceiling. As they reach maturity, they often exhibit increasing unit costs, declining margins and low growth.

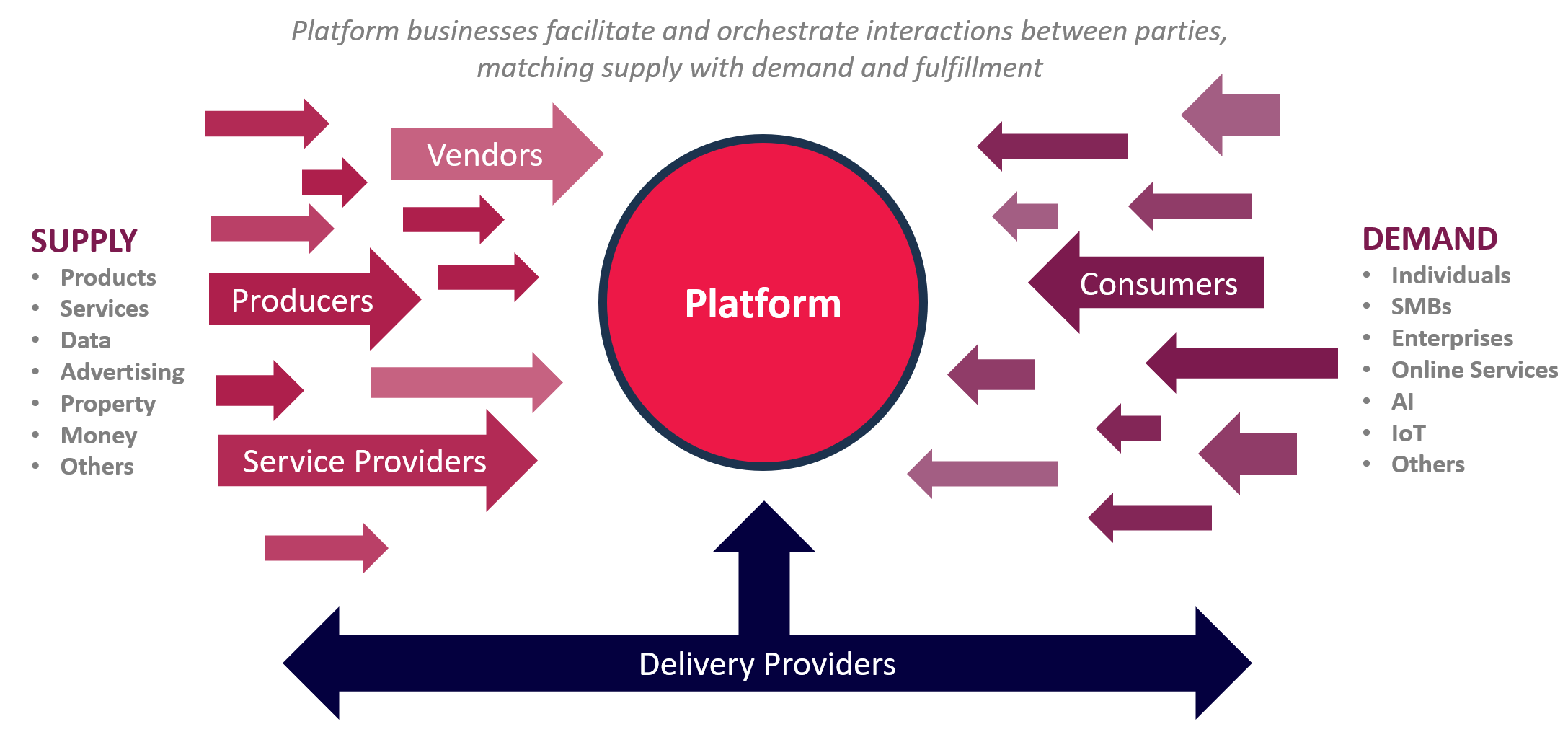

The power of the network

A platform business on the other hand unleashes value by bringing together groups of users to build communities and create markets that facilitate interactions, transactions and the exchanges of products and services.

Platform Businesses

Source: Montaka

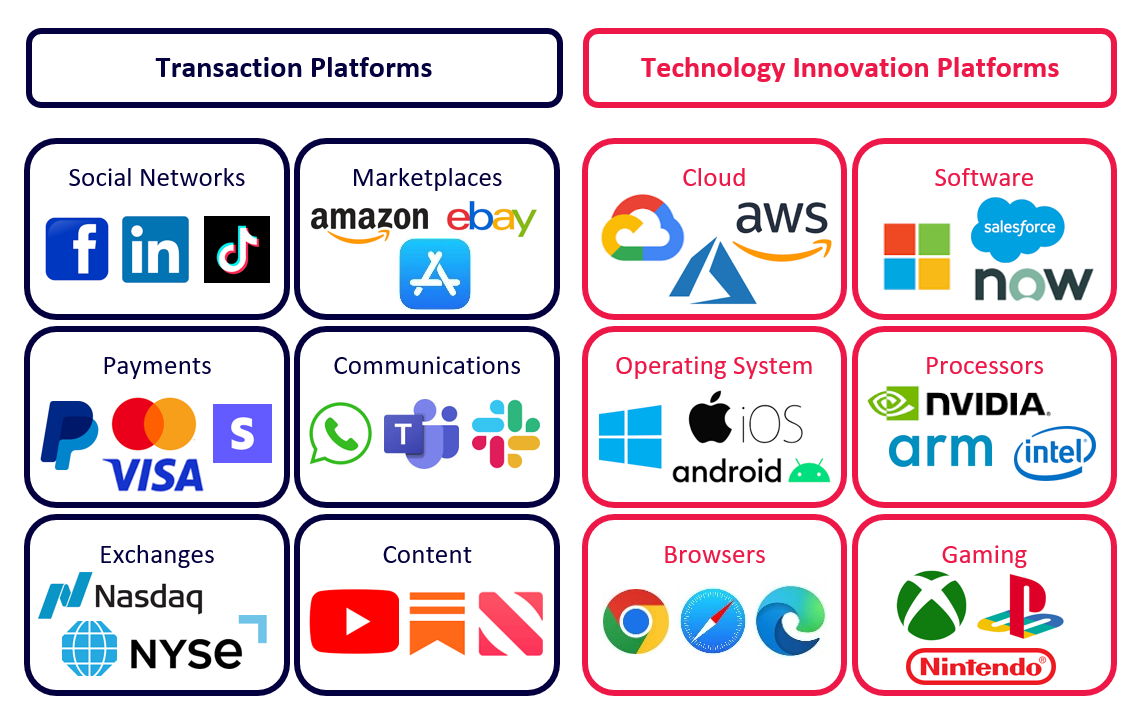

Broadly speaking there are two types of platforms:

1. Transaction platforms

Transaction platforms sit between different users, buyers and suppliers. They act as intermediaries. They facilitate payments directly via a purchase of a product/service. Or they create awareness (aka advertising). Transaction platforms are most commonly consumer focused (B2C), such as Facebook, eBay, WhatsApp and PayPal, though not exclusively.

2. Technology innovation platforms

Technology innovation platforms leverage digital infrastructure and provide the fabric for other companies to build new products and services upon. Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Windows ecosystems, for example, have driven the creation of thousands of new companies which have built their businesses and products on top of their platforms. These types of platforms are typically focused on business customers (B2B).

Examples of Transaction and Technology Innovation Platforms

Source: Montaka

The most critical piece of a platform is its ability to create self-reinforcing network effects. At the most basic level, a network effect occurs when the addition of another user to the platform increases the value of the service for others. The value of Facebook increases as more people use it, there are more people to connect with, more content is shared, more opportunities for it to be seen and hence more advertising dollars are attracted. As this virtuous cycle starts gathering pace and scales (i.e., flywheel), it has incredible gravity, and ultimately can deliver huge investment returns.

Beware of the trapdoor

Unfortunately, identifying a durable network effect is diabolically difficult. What is and is not a platform is hotly debated.

While many companies claim to be platforms and exhibit similar characteristics early in their growth journey, there can be two problems:

- They are often addressing a much smaller market than they know.

- Worse yet, they may simply be capturing the edge of a scale platform’s market opportunity, which could put it in direct competition with one of the most powerful predators in the business jungle, a genuine platform.

These types of companies are actually ‘trapdoors’.

A telltale sign of a platform that is actually a trapdoor is when it cannot capture incremental customers in a cost-efficient way, or fully monetize its existing customer base without losing them to a competitor (churn). If this is the case, the trapdoor’s growth will likely implode and any network effects that may have occurred will start to reverse. Effectively opening a blackhole at the center of the business.

We have seen several examples of platform pretenders that ended up being trapdoors over the last few years.

Trapdoor 1: Peloton

Peloton, the at-home fitness company, surged to extraordinary heights when people were confined to their homes during the pandemic.

Peloton claimed to have a huge addressable market because no one would return to the gym. Its user base enjoyed strong network effects from the community of fitness enthusiasts, and its ability to monetize its affluent customers was extremely high.

Unfortunately, none of these things were true.

The stock fell ~97% from its pandemic peak as the market realized it was simply a linear exercise bike and not a platform business.

The Peloton Trapdoor – Limited TAM, No Network Effect, Unprofitable

Source: Montaka, Bloomberg.

Trapdoor 2: Zoom

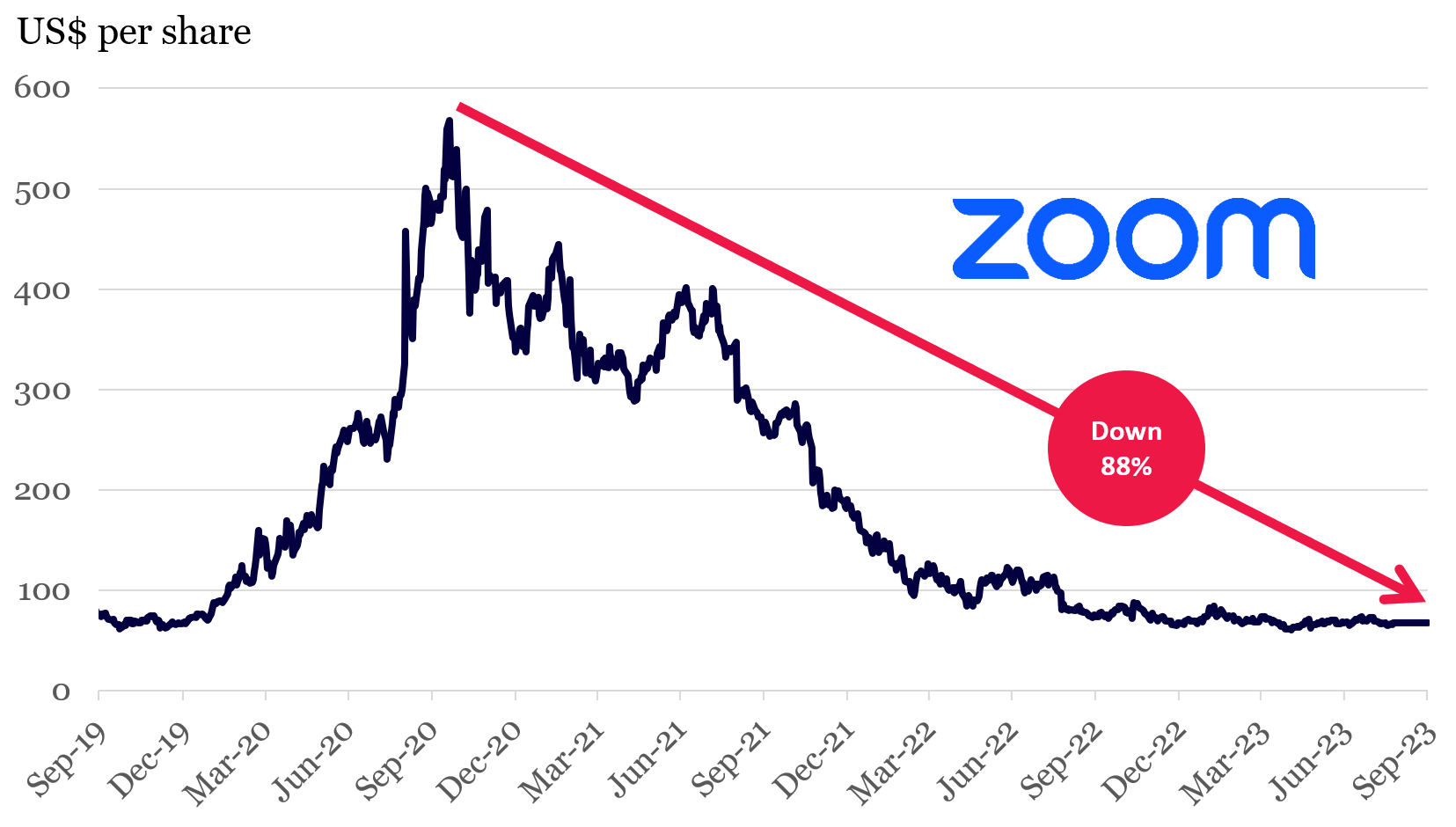

Another example of a recent trapdoor was Zoom.

As business meetings, classrooms and doctors’ visits rapidly moved online, it seemed everyone needed Zoom to participate in the digital economy. Zoom appeared to have strong network effects early in the pandemic.

Microsoft, the world’s leading software platform, had other ideas. Microsoft included its Teams video service for free with its Office subscriptions. Given that much of Zoom’s paying customer base were also Microsoft customers, Zoom experienced significant churn and its early network effect rapidly unwound.

Competing against an entrenched platform like Microsoft in a segment it was aggressively pursuing, proved overwhelmingly difficult for Zoom and its stock has fallen ~88% from its pandemic high.

The Zoom Trapdoor – Competing Against an Entrenched Platform

Source: Montaka, Bloomberg

How to avoid trapdoors

There are three rules to help investors stay away from trapdoors:

1. Stay away from businesses that directly compete with a genuine platform

In the retail industry, most companies will compete with Amazon on some level. In consumer electronics, it’s Apple. In enterprise software it’s Microsoft. However, this is an extremely reductive way of identifying the investable universe and severely limits an investors opportunity set, but it is not a bad strategy to avoid calamity.

2. Avoid early-stage platforms

Another way to avoid a trapdoor is to avoid nascent or early-stage platforms or management teams that are overly promotional in this regard. Statistically speaking it is very unlikely they are a genuine platform.

3. Look for linear businesses

Another option, while acknowledging platform businesses are highly advantaged, may be to focus on linear businesses. Some industries are better served by linear models, like mining and manufacturing, which are heavily resource intensive. Highly regulated industries like banking, insurance and healthcare, are also often better suited to linear models. It is worth noting that these businesses are more likely to be cyclical than secular growth stories and less likely to compound over time. Montaka owns relatively few linear businesses as we focus on long-term compounders for our core portfolio.

Investing in platforms (not trapdoors)

A key signature of a successful platform is when it starts taking over entire industries and adjacent markets while becoming increasingly profitable. At the same time linear competitors bleed margin and struggle to retain customers against the gravitational pull emanating from the platform’s network effects. It can be an exciting time for investors watching a platform’s growth – and share price – explode.

But the lure of chasing those big returns can catch out investors. Rather than a powerful platform, they can instead find themselves invested in a trapdoor and suffer big losses or underperformance.

At Montaka we believe in owning long-term winners in attractive markets while they remain undervalued. We are firmly focused on investing in genuine platform business models and avoiding trapdoors.

With industries and businesses increasingly characterized by winners and losers, Montaka’s holdings in several leading and emerging platforms provide us with the greatest chance of winning over the long-term.

Amit Nath is the Director of Research at Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Tech is dead? Think again. Montaka’s new white paper argues that far from dying, tech is entering a remarkable new era of growth with huge opportunities for investors.

To request a copy of the full whitepaper & know the top 5 stocks poised to lead the tech recovery, please share your details with us: