|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

We manage a portfolio of earnings streams and cash holdings denominated in a range of currencies. It is important, therefore, to: (i) be clear about the exposures that are contained in the portfolio; and (ii) ensure that these exposures are sensible in light of the global economic environment in which we find ourselves.

We seek to preserve global purchasing power for all our investors. We believe we will achieve this over time by maintaining a globally-diversified portfolio of currency exposures – adjusted for any short and medium-term views we hold with respect to the broad directions of major global currencies.

Two currency trends surprised us in 2017: (i) the weakness in the US dollar; and (ii) the strength in the Chinese Renminbi. We have found that the commentary and analysis of these issues to be generally underwhelming. So, we decided to go back to first principles to see if we could uncover some logical forces that are driving the global major currencies today.

We rely heavily on the teachings of Professor Michael Pettis; and his outstanding book The Great Rebalancing, for these first principles.

The classic explanation of imbalances

Pettis points out early on that: “the classic explanation of the origin of crises in capitalist systems… points to imbalances between production and consumption in the major economies as the primary source of monetary instability.”

While Pettis was giving consideration to the underlying drivers of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), these same imbalances exert force on global currencies and are worth trying to understand. Pettis goes on: “Imbalances in one country can force obverse imbalances in other countries through the trade account.”

The link between domestic savings, domestic investment and a country’s current account – which is a measure of the flow of transactions between the country and the rest of the world, including trade, financial income and transfers – is not immediately clear and often counterintuitive. Pettis explains this as follows:

“Every country’s current account surplus is by definition equal to the excess of domestic savings over domestic investment. If a country saves more than it invests domestically, these excess savings must be invested abroad, and one of the automatic consequences of net foreign investment is an excess of exports over imports… Every country that has net investment abroad must generate more revenues from the export of goods and services and from foreign interest and royalty payments than it pays out.” This is the link between domestic savings and investment and the trade account.

Former US Treasury economist, Kenneth Austin, explains the same concept like this:

“Increasing foreign investment requires earning the necessary foreign exchange to invest abroad. This requires an increase in net exports. So foreign investment solves two problems at once. It reduces the excess supply of goods and drains the pool of excess saving.”

In this sense, current account surplus countries can be said to be doing both of these things at once – because they are, by definition, equivalent:

- Exporting excess savings as capital to the rest of the world;

- Importing demand to its own economy.

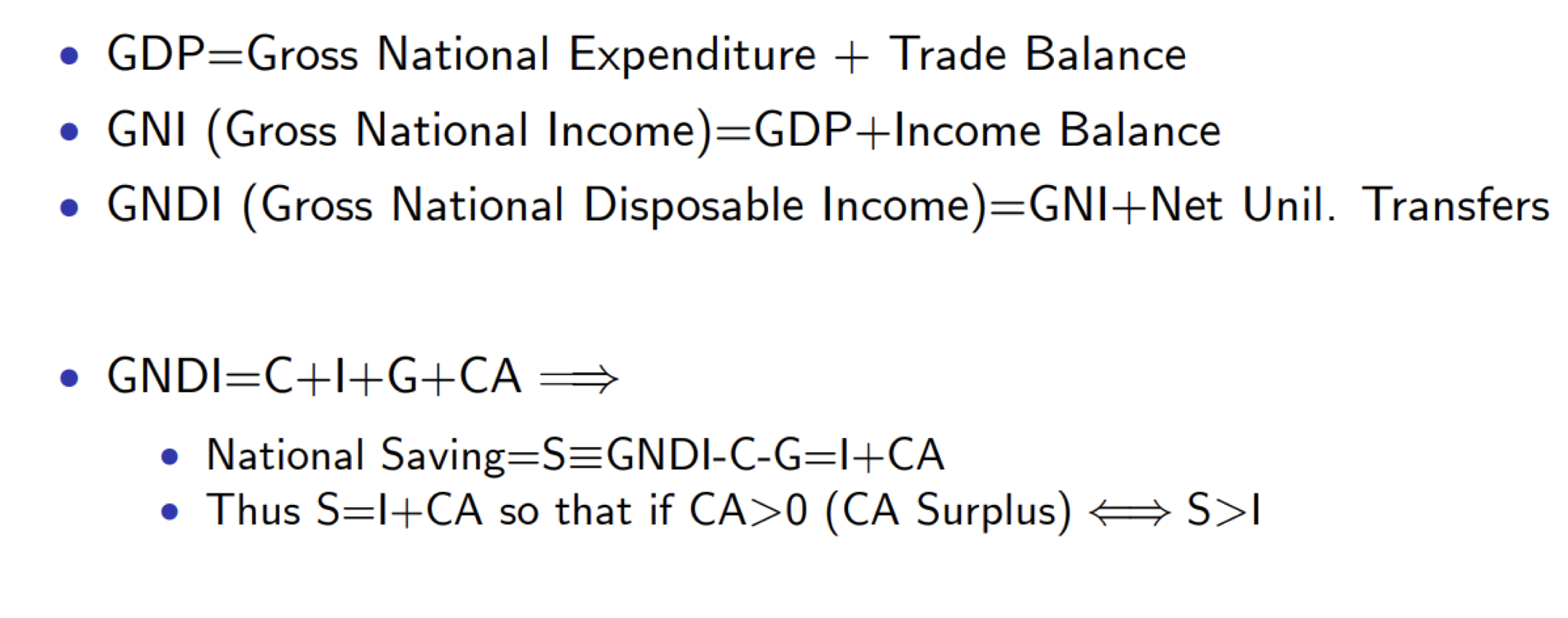

(We include a basic derivation of the relationship between savings, investment and the current account in the Appendix).

Finally, Pettis stresses that:

“Large and persistent trade balances are almost always caused by distortions in financial, industrial or trade policies. For trade deficit countries, the large deficits led to unsustainable increases in debt and, ultimately to a deleveraging process necessary to restore balance. (It was this deleveraging process that was at the heart of the GFC).” In light of new fiscal, monetary and trade policies being announced in the US, China and elsewhere, we believe this framework will be valuable in navigating the months and years ahead.

So to recap, a country’s domestic growth is driven by three sources: (i) domestic consumption; (ii) domestic investment; and (iii) net consumption and investment from abroad – which is the current account surplus. And it is the change in the current account that acts as a force on a country’s domestic currency: an increasing current account corresponds to increased demand for a country’s domestic currency; and vice versa.

In the next three parts of this blog, we give consideration to the trajectories of savings and investment of the major global economic blocs (and Australia) to see if we can make any sensible assessments of the likely trajectories of their associated current accounts and domestic currencies.

Appendix – The relationship between savings, investment and the current account

![]() Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.