By Andrew Macken

In a recent interview[1], Australian-born math prodigy, Terence Tao, spoke of three distinct ‘ontological’ aspects to reality. First, there’s actual reality. Second, there’s observations, or samples, taken from reality. And third, there’s our models of reality.

The idea is simple enough, yet so powerful. Applied to our world of investing (more poetically than precisely), it reminds us that investors – even those who undertake meticulous study – can never fully know the reality inside their investee companies.

Only a set of observations, or ‘samples’, from inside the company can be analyzed: things like financial statements, company presentations, interviews with staff, or market prices.

And just as humankind’s conceptual models (everything from triangles, to gravity, to Schrodinger’s wave function) are so critical to helping us move closer to understanding true reality, investors need to have models that frame these company ‘samples’ so they can usefully (and valuably) classify, and move closer to, the underlying reality of the (unobservable) business.

At Montaka, some of the most important models we use to assess and classify businesses are models of competitive intensity.

When a company has competitive advantages, they generally face less intense competition, are better protected from new competition, and have a greater chance of delivering higher returns on invested capital over time. And vice versa for competitive disadvantages.

In this article we explore the ‘flywheel’ – a powerful model for how competitive advantages are built and strengthened over time.

A ‘space’ of competitive advantages

In mathematics, many believe that we are simply discovering objective truths that exist in the abstract – a ‘Platonic space’ independent from human minds and physical reality.

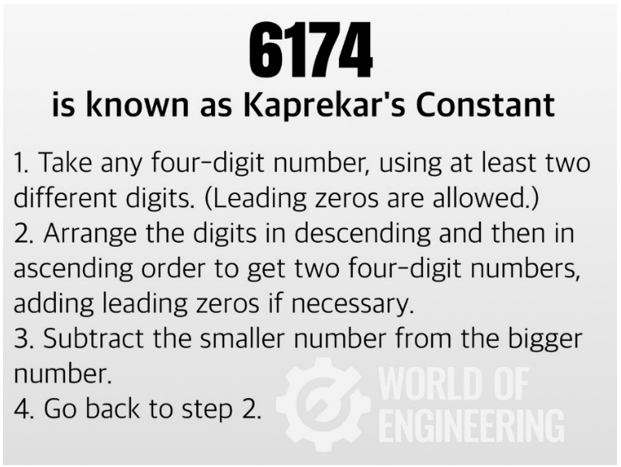

Take Kaprekar’s Constant, discovered 76 years ago. India’s D.R. Kaprekar discovered that the following simple algorithm always leads to the number 6174:

Platonists would argue that this simple truth – one of many in the vast Platonic space of mathematics – would exist with or without physical reality and human thought.

We again employ some poetic license to transfer this idea to the world of investing.

Could the various forms of competitive advantages and disadvantages that a company might exhibit exist in its own simple Platonic space?

Imagine a ‘space’ that mapped:

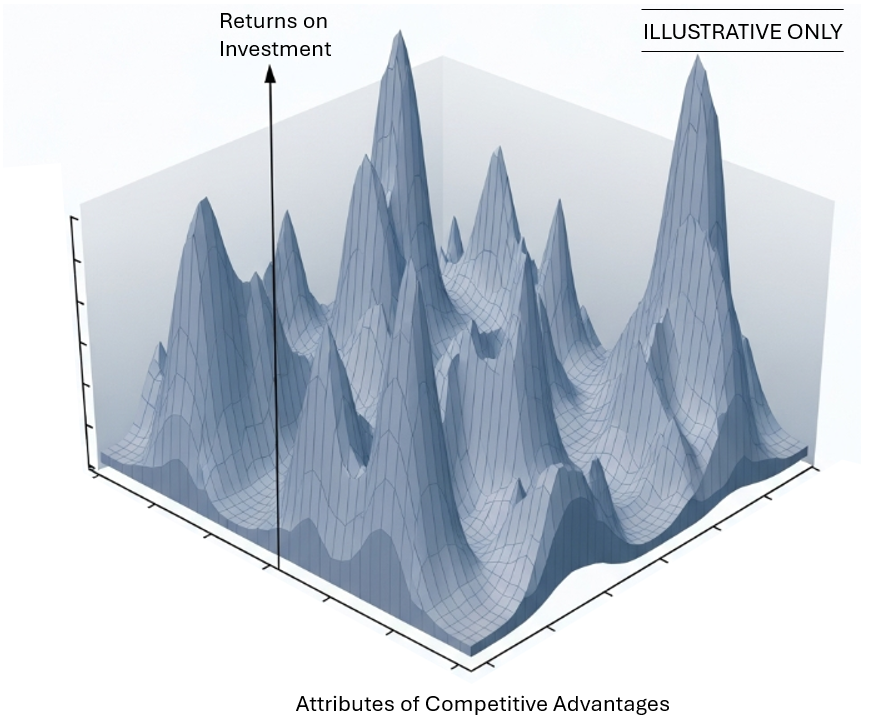

- Intense competition and low returns to business models that sell commodity products with little differentiation, high substitutability, and low barriers to entry. These would be represented by the ‘troughs or low points on the illustrative schematic above.

- Business models with economies of scale and cost-advantages that increased barriers to entry and reduced competitive intensity. These attributes typically enable higher returns on invested capital and would be represented by peaks in the schematic above.

- Similarly, business models with a high degree of customer captivity and where pricing power was strong because of high customer switching costs would also be represented by peaks in the above schematic as they too enable higher returns on investment.

One could even imagine combinations of scale and customer captivity that form even higher ‘peaks’ of competitive protection and, therefore, investment returns. Platform business models would live in these high points of this particular Platonic space, for example, as would network business models.

A self-reinforcing cycle

An important question for investors (as well as business executives) is: How can a business build and strengthen its business advantages? Or building on our schematic above, how can a business evolve to even higher peaks in the Platonic space?

Our answer is: ‘flywheels’.

A ‘flywheel’ is a dynamic in which economics are shared between the company and its customer to form a symbiotic relationship of collective benefit.

When the customer and company win together, we often see greater customer adoption and retention, increased market share, greater scale, greater enhancement of the product or service offering – and the advantages described above growing in strength over time.

The dynamic is self-reinforcing: the more the business shares with its customers, the faster its advantages grow.

Like a flywheel in the physical world, once it gathers steam, it’s very difficult to stop.

Employing our flywheels model to identify opportunities in disparate places

In a recent presentation to investors, I asked what the companies on the left (below) all have in common. To someone merely observing financial ‘samples’ from each of these businesses, it’s not obvious what a payments company has in common with a retailer, or what an asset manager has in common with an audio streaming platform. (Of course, all of these companies are owned by Montaka at present).

Only with the conceptual model of ‘flywheels’ can the investor connect these seemingly disparate businesses.

Let’s look at three examples:

- Firstly, Spotify. With a free ad-supported tier and a low subscription price, customers get enormous value at minimal cost. As more people use the service, Spotify learns more about consumer preferences, data that informs how the company can improve the value of the service for all users even more.

- Or consider the retailer, Floor & Decor. By specializing only in hard surface flooring, they can leverage greater scale in their direct ordering from manufacturers. By sharing these reduced costs with customers through lower prices, and by offering the widest range of SKUs (stock keeping units) on the retail floor, more customers adopt and are retained, which in turn further increases market share and scale.

- Even Blackstone and KKR, the world’s leading alternative asset managers exhibit flywheel dynamics. With the greatest scale around the world, and full-service offerings across the entire capital structure, they can source the most attractive deals. These attributes attract the world’s largest clients, as well as the highest-caliber deal-making talent – all of whom mutually benefit from greater investment returns over time. Furthermore, with some of the largest investment portfolios in the world, Blackstone and KKR can leverage their proprietary data sources to identify new investment trends before they are recognized by the competition, further increasing expected investment returns.

From conceptual models to investment returns

Employing models of competitive advantages and flywheels to give meaning to observed financial samples is more than just an interesting conceptual analysis. It has a direct path to long-term investment returns.

With competitive advantages, companies can capture superior returns from business investments. That includes when they expand their core businesses, but also when they leverage their core advantages to expand into new, adjacent markets. Superior returns manifest as higher growth in earnings power (relative to the capital investments required to achieve said growth).

Flywheels build and strengthen competitive advantages of companies, making them relatively more resilient to the ebbs and flows of economic and political cycles. They increase the probability of more reliable growth over extended time horizons.

And this is the very dynamic that is routinely undervalued by markets.

To capture these inefficiencies in long-duration opportunities, academic and empirical research[2] has found that asset managers need to adopt active management strategies characterised by two things:

- High active share (a large difference between the portfolio and benchmark) – the result of a highly-concentrated portfolio, and

- Long fund duration (positions held for extended periods) – the result of long-term patience in individual investments.

This is why Montaka believes that owning a long-term and high-conviction portfolio of high-quality global companies – those with strong and strengthening competitive advantages – represents a persistent long-term alpha opportunity.

And we can build and hold that portfolio by using models of competitive advantages – as well as the flywheel model – models that help us understand the true ‘reality’ of powerful businesses.

Note:

[1] (Lex Fridman Podcast) Terence Tao: Hardest Problems in Mathematics, Physics & the Future of AI (June 2025)

[2] (Montaka) Concentrated, Patient & Disciplined — The 3 Pillars of Active Management Outperformance, 2023

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100 or leave us a line at montaka.com/contact-us

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.

Why Competitive Advantages Matter – And How Flywheels Make Them Stronger

By Andrew Macken

In a recent interview[1], Australian-born math prodigy, Terence Tao, spoke of three distinct ‘ontological’ aspects to reality. First, there’s actual reality. Second, there’s observations, or samples, taken from reality. And third, there’s our models of reality.

The idea is simple enough, yet so powerful. Applied to our world of investing (more poetically than precisely), it reminds us that investors – even those who undertake meticulous study – can never fully know the reality inside their investee companies.

Only a set of observations, or ‘samples’, from inside the company can be analyzed: things like financial statements, company presentations, interviews with staff, or market prices.

And just as humankind’s conceptual models (everything from triangles, to gravity, to Schrodinger’s wave function) are so critical to helping us move closer to understanding true reality, investors need to have models that frame these company ‘samples’ so they can usefully (and valuably) classify, and move closer to, the underlying reality of the (unobservable) business.

At Montaka, some of the most important models we use to assess and classify businesses are models of competitive intensity.

When a company has competitive advantages, they generally face less intense competition, are better protected from new competition, and have a greater chance of delivering higher returns on invested capital over time. And vice versa for competitive disadvantages.

In this article we explore the ‘flywheel’ – a powerful model for how competitive advantages are built and strengthened over time.

A ‘space’ of competitive advantages

In mathematics, many believe that we are simply discovering objective truths that exist in the abstract – a ‘Platonic space’ independent from human minds and physical reality.

Take Kaprekar’s Constant, discovered 76 years ago. India’s D.R. Kaprekar discovered that the following simple algorithm always leads to the number 6174:

Platonists would argue that this simple truth – one of many in the vast Platonic space of mathematics – would exist with or without physical reality and human thought.

We again employ some poetic license to transfer this idea to the world of investing.

Could the various forms of competitive advantages and disadvantages that a company might exhibit exist in its own simple Platonic space?

Imagine a ‘space’ that mapped:

One could even imagine combinations of scale and customer captivity that form even higher ‘peaks’ of competitive protection and, therefore, investment returns. Platform business models would live in these high points of this particular Platonic space, for example, as would network business models.

A self-reinforcing cycle

An important question for investors (as well as business executives) is: How can a business build and strengthen its business advantages? Or building on our schematic above, how can a business evolve to even higher peaks in the Platonic space?

Our answer is: ‘flywheels’.

A ‘flywheel’ is a dynamic in which economics are shared between the company and its customer to form a symbiotic relationship of collective benefit.

When the customer and company win together, we often see greater customer adoption and retention, increased market share, greater scale, greater enhancement of the product or service offering – and the advantages described above growing in strength over time.

The dynamic is self-reinforcing: the more the business shares with its customers, the faster its advantages grow.

Like a flywheel in the physical world, once it gathers steam, it’s very difficult to stop.

Employing our flywheels model to identify opportunities in disparate places

In a recent presentation to investors, I asked what the companies on the left (below) all have in common. To someone merely observing financial ‘samples’ from each of these businesses, it’s not obvious what a payments company has in common with a retailer, or what an asset manager has in common with an audio streaming platform. (Of course, all of these companies are owned by Montaka at present).

Only with the conceptual model of ‘flywheels’ can the investor connect these seemingly disparate businesses.

Let’s look at three examples:

From conceptual models to investment returns

Employing models of competitive advantages and flywheels to give meaning to observed financial samples is more than just an interesting conceptual analysis. It has a direct path to long-term investment returns.

With competitive advantages, companies can capture superior returns from business investments. That includes when they expand their core businesses, but also when they leverage their core advantages to expand into new, adjacent markets. Superior returns manifest as higher growth in earnings power (relative to the capital investments required to achieve said growth).

Flywheels build and strengthen competitive advantages of companies, making them relatively more resilient to the ebbs and flows of economic and political cycles. They increase the probability of more reliable growth over extended time horizons.

And this is the very dynamic that is routinely undervalued by markets.

To capture these inefficiencies in long-duration opportunities, academic and empirical research[2] has found that asset managers need to adopt active management strategies characterised by two things:

This is why Montaka believes that owning a long-term and high-conviction portfolio of high-quality global companies – those with strong and strengthening competitive advantages – represents a persistent long-term alpha opportunity.

And we can build and hold that portfolio by using models of competitive advantages – as well as the flywheel model – models that help us understand the true ‘reality’ of powerful businesses.

Note:

[1] (Lex Fridman Podcast) Terence Tao: Hardest Problems in Mathematics, Physics & the Future of AI (June 2025)

[2] (Montaka) Concentrated, Patient & Disciplined — The 3 Pillars of Active Management Outperformance, 2023

Podcast: Join the Montaka Global Investments team on Spotify as they chat about the market dynamics that shape their investing decisions in Spotlight Series Podcast. Follow along as we share real-time examples and investing tips that govern our stock picks. To listen, please click on this link.This content was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.