|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Part I of this four part blog, we went back to first principles of savings, investment and trade. We now seek to give consideration to the trajectories of savings and investment of the major global economic blocs to see if we can make any sensible assessments of the likely trajectories of their associated current accounts and domestic currencies.

The future of US savings and investment

While not explicitly called as such, the US government is currently engaging in two new forms of fiscal stimulus:

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (i.e. Trump’s tax cuts) – which is believed to equate to an approximately $1.5 trillion increase in federal debt over the next decade. We believe it is more likely than not that the true increase in the deficit will be materially more than $1.5 trillion.

- The two-year (unfunded) Budget Deal, passed on February 8, which will increase investments in domestic programs and the military by approximately $300 billion over the next two years.

In rough numbers, these two policies alone will add around 1.6 percent of GDP per year of new unfunded government spending (or consumption) into the US economy over the next two years. And we believe these policies will result in significant consequences for both domestic savings and investment.

The fiscal stimulus described above will likely increase domestic consumption. At a minimum, it is a direct increase in “government consumption”, though household consumption will likely increase as well, given short-term income tax cuts for many Americans combined with a positive wealth effect from the booming stock market.

A consequence of a strong increase in domestic consumption is, logically, a significant decrease in the national savings rate. (Savings, here, meaning the difference between what the economy produces and what it consumes).

Meanwhile, there is a strong argument that domestic investment will increase. In part, this is due to the favourable tax treatment (full expensing) of new domestic capital investments for the next five years under Trump’s tax reforms.

Combining the two would result in a declining savings rate combined with an increased investment rate. This would equate to a larger current account deficit. (Ironically, this outcome is precisely the opposite of what President Trump has been saying he wants). And recall, if the US increases its current account deficit, then other economies will, by definition, increase their current account surpluses.

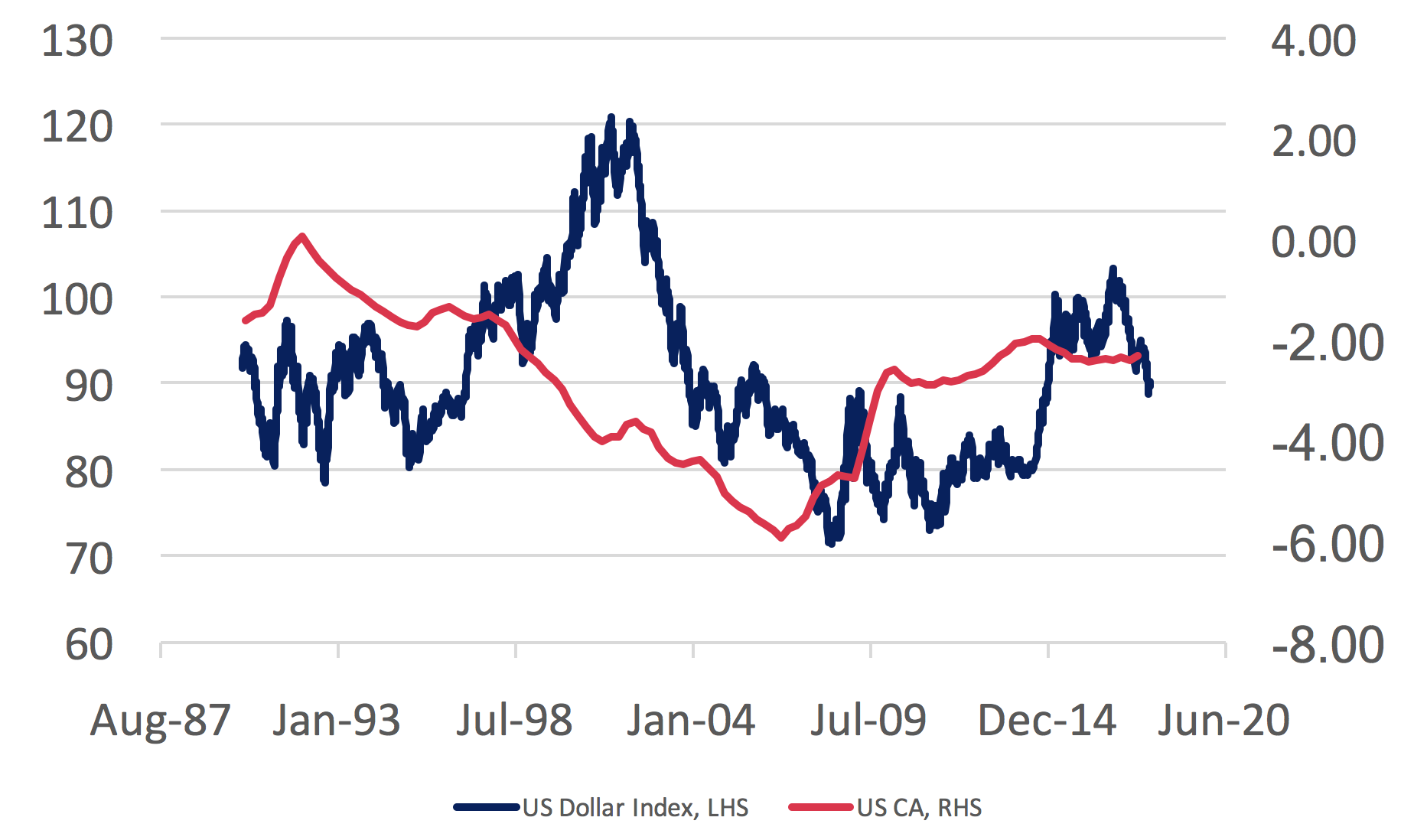

An increasing current account deficit would likely result in downward pressure on the US dollar in the near-term.

On a medium-term basis, there is the potential for the US economy to overheat and monetary policy to tighten to keep inflation at acceptable levels. Higher interest rates would likely temper domestic consumption, increase the savings rate and reduce the current account deficit. This would be positive for the US dollar.

US Dollar Index vs US Current Account (% of GDP)

Source: Bloomberg

The future of Chinese savings and investment

To assess the future trajectory of Chinese savings and investment, one needs some historical context around the key drivers of the Chinese economy.

Over the last two decades, China’s economy has been almost entirely driven by growth in domestic fixed-asset investment. Despite such significant investment, China’s savings rate has been very high. China’s high savings rate was engineered by policymakers through very low bank deposit rates. Low deposit rates supressed household wealth and resulted in household consumption remaining weak relative to total domestic consumption – and hence a high national savings rate.

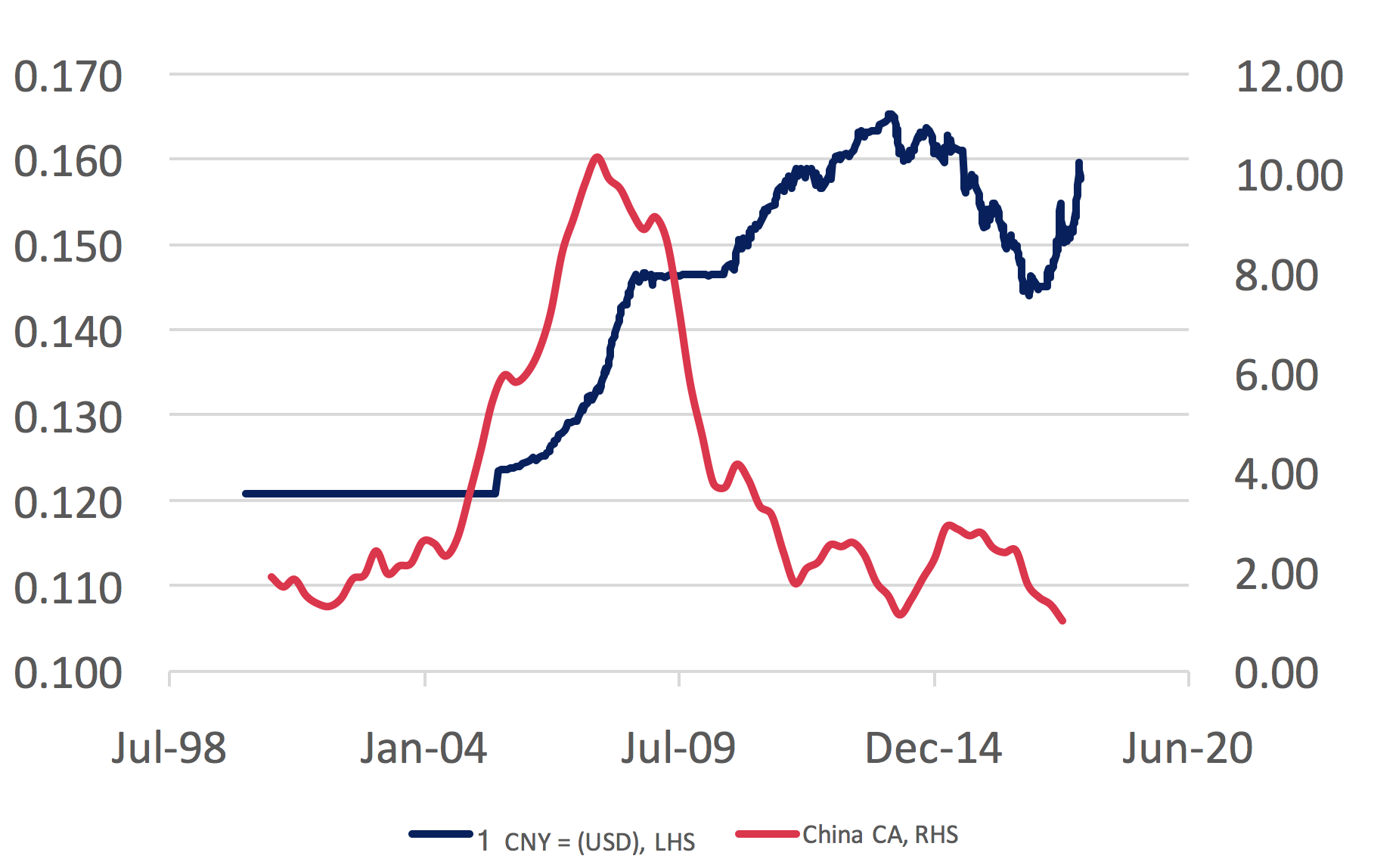

These savings were exported abroad via China’s large current account surplus. Said another way, demand was imported from current account deficit countries, such as the US, to absorb China’s excess production. China’s strong current account surplus resulted in upward pressure on the Renminbi, which was allowed to appreciate in a very controlled fashion, as shown below. (Recall, the Renminbi is not a free-floating currency, the nuances of which we have written about previously).

Renminbi vs China Current Account (% of GDP)

Source: Bloomberg

Considering the current trajectory of Chinese savings and investment, we make the following observations:

- While China’s economic growth has remained strong since its 2016 stimulus, it has been outpaced by consumption over the last four years.[1] Said another way, China’s national savings rate has been declining. We would expect this to continue.

- China’s fixed-asset investment growth continues to slow, despite a sharp reacceleration in State-sponsored investment growth in 2016.

- Over the last two years, domestic savings declined at a faster rate than domestic investment, resulting in a decline in China’s current account surplus to just one percent of GDP.

One would typically expect downward pressure on a domestic currency in light of a reducing current account surplus. Instead, since the beginning of 2017, the Renminbi has appreciated by around 10 percent against the US dollar (though not against the Euro or the Japanese Yen).

Looking ahead, we expect the above dynamics to continue with the one caveat that we would expect overall growth, including consumption growth, to slow following the great stimulus of 2016. We still expect consumption to outpace total growth, reducing the national savings rate further. But we could well see a more severe slowing in fixed asset investment. This could actually result in a rebound of China’s current account surplus, though the direction is not as clear cut.

Finally, it is interesting to consider whether or not China would repeat its surprise devaluation of August 2015. Such a devaluation would increase the cost of imported goods to households (households are net importers) and likely reduce household consumption. In the meantime, net exports would be boosted, pushing aggregate economic growth. The combination of these two dynamics would likely result in an increase in excess savings, an increase in China’s current account surplus and upward pressure on the Renminbi.

Economically, such a surprise devaluation does not make sense since China is already in a current account surplus position. Geopolitically, this perhaps becomes a weapon if the US and China find themselves in a tit-for-tat trade war down then track.

[1] (China Daily) Chinese consumption posts faster growth than GDP, February 2018

![]() Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Andrew Macken is Chief Investment Officer with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.