Make sense of the global investment landscape with timely updates, articles and videos from our investment experts

Montaka

- Active ETF

Global Fund

ASX: MOGL

Montaka Global

Long Only Fund

Montaka Global

- Complex ETF

Extension Fund

ASX: MKAX

Sydney

Suite 2.06, 50 Holt Street

Surry Hills, NSW 2010

Australia

Copyright © 2022 Montaka Global

Privacy | Terms | Disclaimer | FSG | TMD

Why barriers to exit are killing commodity prices

Many investors understand the importance of “barriers to entry” to an industry. If an industry is difficult, time-consuming or prohibitively expensive to enter, then-incumbent industry players will be protected from competition. This is an attractive characteristic for the shareholders of said incumbents and usually results in the industry generating above-average industry returns.

Fewer investors consider the notion of “barriers to exit” with respect to industry. And even fewer, the consequences of such barriers. Many commodity producers are currently facing barriers to reduce production capacity; and this in turn, is exacerbating enormous oversupplies in many commodity sectors resulting in further price declines.

The concept of barriers to exit can be somewhat counterintuitive. After all, if I own a mining project, surely I can simply tell all my employees to pack up and go home, thereby exiting the sector. But it’s not quite that simple. As Macquarie highlighted back in November last year, there are at least 10 factors that can hinder the reduction of capacity within commodity sectors – many of which can be conceptually extended to other sectors as well.

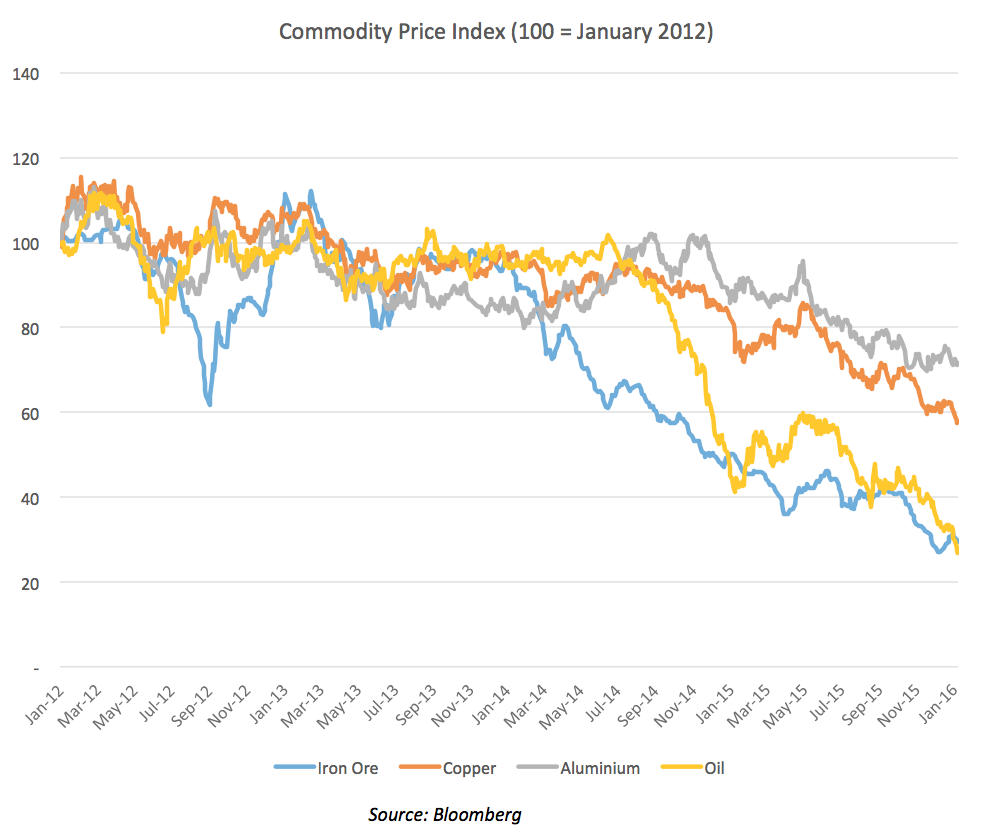

These factors described above have dramatically hindered the rate of supply cuts that declining commodity prices over recent years should have encouraged. And this, in turn, has meant commodity prices have continued to fall, as shown below. Many of these barriers to exit continue to persist. In our view, therefore, the pain still to come in these sectors can be measured in years, not months.

This document was prepared by Montaka Global Pty Ltd (ACN 604 878 533, AFSL: 516 942). The information provided is general in nature and does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read the offer document and consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs before acting upon this information. All investments contain risk and may lose value. Consider seeking advice from a licensed financial advisor. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Related Insight

Share

Get insights delivered to your inbox including articles, podcasts and videos from the global equities world.