|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Last week Apple reported its fourth quarter and full fiscal year results. While the quarter past was strong, Apple’s underwhelming guidance for the first quarter of fiscal 2019 combined with its decision to cease reporting unit shipments for the iPhone, iPad and Mac in future drove a $70 billion wipeout of market capitalisation. If one were to jump to conclusions, the most comfortable conclusion would be that Apple no longer believes iPhone units will grow and wants to hide this fact by not reporting. But is this reporting change as concerning as the market makes it out to be, or has this been a long time coming?

Apple has always prided itself on being better than the competition, and that includes its disclosure. For context, Apple has been reporting unit sales since the 1980s, and was until last week the only major consumer hardware company to still do so. Therefore, Apple’s decision to no longer report units for the iPhone, iPad and Mac shouldn’t be surprising in and of itself. What is suspicious, though, is the timing – Apple could have stopped reporting iPhone units at any point during the past decade of the iPhone’s existence, but only chose to do so now when the high-end smartphone market is saturated, and investors are already concerned about stagnant volumes. Steve Jobs himself once said, “Usually, if they sell a lot of something, you want to tell everybody” when criticising a competitor’s lack of disclosure.

Naturally, such a decision would be perceived in a negative light. What is more suspicious, though, is that Apple chose to justify this reporting change after a quarter where iPhone revenuesgrew 29% year-over-year. From CFO Luca Maestri:

“When you look at our financial performance in recent years, take the last three years, for example, the number of units sold during any quarter has not been necessarily representative of the underlying strength of our business. If you look at our revenue, given the last three years, if you look at our net income during the last three years, if you look at our stock price here in the last three years, there’s no correlation to the units sold in any given period.”

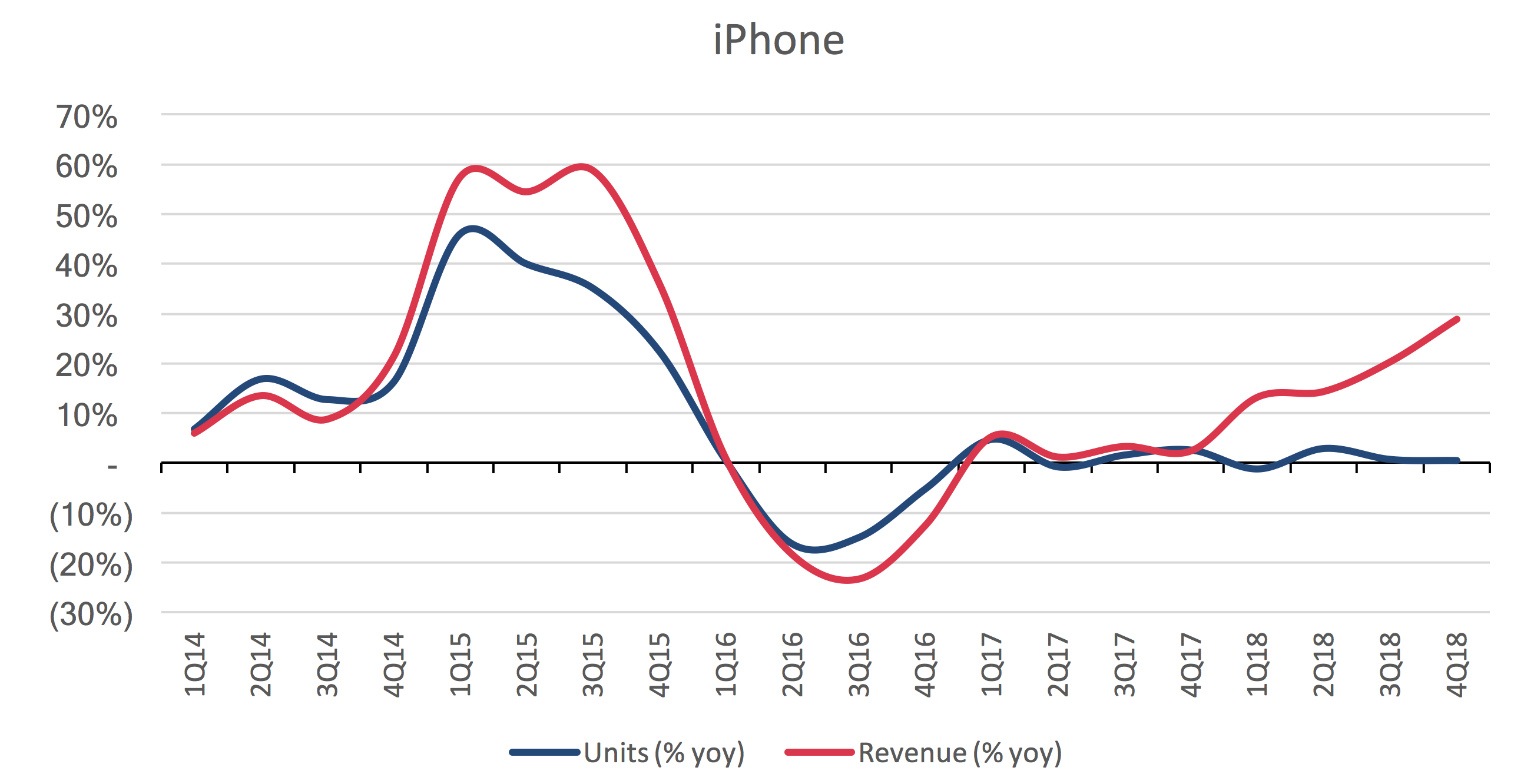

What Maestri is referring to is effectively this chart:

Specifically, Maestri is using the progressive divergence between iPhone units and revenue since 1Q18 to justify Apple’s position that units are now a less relevant measure of the company’s health. (His comment about the last three years considers Services revenue as well, but here we are only concerned with the iPhone.) But that divergence has been driven by a 17% increase in annual iPhone Average Selling Price (“ASP”) and a whopping 28% year-over-year increase in 4Q18 ASP. How regularly can any company, even one with as much pricing power as Apple, pull off 20%-plus annual price increases on $1,000 smartphones?[1]We would wager not often, and indeed the guidance for 1Q19 suggests the red line falls right back down to where the blue line is.[2]

But Apple is not just trying to decrease its transparency. In place of unit shipments, Apple will now disclose cost of sales separately for its Products line and Services line, in the clearest move to shift the narrative from a mature iPhone market to the fast-growing Services segment. That segment exited 4Q18 at a $40 billion annualised revenue run rate and is well ahead of management’s $48 billion target for fiscal 2020. This isn’t the first time Apple has tried to shift the narrative – CEO Tim Cook started dropping hints about Apple’s Services transition as early as 1Q16 – but only now will investors get a quantitative appreciation of the profitability and importance of the Services business.

We have written about the importance of Apple’s Services business on numerous occasions in the past, so it is good to receive further validation of this leg of our Apple thesis. However, the Apple Services narrative remains critically incomplete, largely because there is no way by which to measure the health of the Services business beyond revenue growth and (soon) gross margin. Typical “services” businesses with recurring revenues are either driven by users and advertising (e.g. Facebook) or by subscribers (e.g. Adobe). In any case, there is usually some measure of a user base that can be multiplied by some measure of revenue per user. Apple, unfortunately, only sporadically discloses total active devices (when reaching milestones e.g. 1 billion), regularly provides “subscriber” numbers and has no intention of disclosing total users because management believes it is not important relative to total active devices.

This leaves investors in a pickle. Using the sporadically-disclosed total active devices to calculate an “Average Revenue Per Device” could lead investors to overestimating the revenue potential of Services, because some users own more than one device, but a user who owns three devices is not going to be spending three times as much in the App Store or on Apple Music as a user with just one device. The subscriber count that Apple regularly discloses is also somewhat meaningless, as it includes only users who subscribe to Apple services such as Apple Music and iCloud, or to third party apps in the App Store. This ignores users who make one-off app purchases or even regular in-app purchases without a “subscription”, and thus “Average Revenue Per Subscriber” could be overstating how much each actual user spends on services, thus underestimating the revenue runway.

Disclosure issues aside, Apple’s very culture, organisation and modus operandi – to design and manufacture consumer hardware that is as close to perfect as practical – is the very antithesis of the fast-iterating, open platform style services business. Apple’s requirement to control all aspects of the hardware, software and user interface, while allowing for a superior user experience, limits the Apple ecosystem’s potential as a true services platform. This is the ultimate dilemma for Apple – to shift the narrative away from what has historically made Apple the most valuable company in the world, it may have to compromise on what set it apart from the myriad of competition in the first place.

Apple remains a very high-quality business, but no business can remain a great investment at every price. The unfortunate reality is that while our early variant perception around the value of Apple’s Services business (when the market was freaking out over declining iPhone sales) gave us confidence that Apple was a bargain at $100 or even $160, the market has since caught on to the Services narrative, pushing the stock price higher and higher and compressing our margin of safety with respect to the considerations discussed above. For a value investor, using quality to justify a higher price is tantamount to putting the cart before the horse. Accordingly, we trimmed our Apple position ahead of earnings on valuation grounds and due to US/China tariff concerns, and ultimately protected our investors’ capital.

Montaka owns shares in Apple (Nasdaq: AAPL)

[1]Apple did introduce higher-priced phones again with the XS Max and the XR, the former being a larger version of the XS at $100 more and the latter intended as a replacement for the 8 series at a $50 premium. But in terms of directly comparable flagships, the XS is the same price as last year’s X model. Come next year, Apple will have already played the “size” card with the XS Max and the “inbetween” card with the XR.

[2]1Q19 guidance does consider a tougher year-over-year comp, as the more-expensive X was released in 1Q18 while the less-expensive XR will be released in 1Q19, therefore potentially depressing the ASP. However, because Apple is no longer reporting unit shipments, we will not be able to confirm if the flat iPhone revenue guide is due to ASP or units.

![]() Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montaka Global Investments. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.