|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The passive investing debate is one over which no shortage of ink (and pixels) have been spilled. What active managers had hoped to be a topic du jour has turned into a seismic shift for the investment industry, and one that has accelerated with each passing year. With passive strategies accounting for nearly 40% of US mutual fund asset and predictions that passive funds could control more than half of overall equity and bond markets by the next decade, we must consider if passive investing really is the perpetual motion machine of wealth creation.

As a timely reminder of where we stand in the current market cycle, Howard Marks, the Chairman of Oaktree Capital, came out with a new memo last week. In it, he identifies four defining features of the current environment that investors need to be cognisant of. While followers of Marks’ writings may feel a sense of déjà vu, his warnings, particularly on the topic of passive investing, are increasingly relevant to anyone trying to navigate today’s uncertain investment environment.

The four features are:

- Asset prices are high across the board. Equity markets are priced well above historical median levels, developed and emerging market bond yields are at or near record lows, volatility expectations are at record lows, and Australians are more than familiar with record high property prices.

- Despite high prices across the board, pro-risk behaviour is commonplace. Due to the negative/zero/low interest rates set by the central banks, investors have been forced up the risk curve to achieve the level of returns they desire or require. The current bull market is often described as the least exuberant bull market in memory. Investors know that asset prices are high and risk-adjusted returns likely to be low, but see no alternative to being invested in risky asset classes when the return on cash is close to zero.

- Given the high starting prices and ongoing pro-risk behaviour, prospective returns are just about the lowest they’ve ever been. During the latter stages of a bull market, investors tend to forget that returns are i) meant to compensate for risk taken, and ii) a function of not just the future price, but also of the entry price paid. Our view at Montaka is that equity returns over the last 30 years have been driven by the tailwinds of higher productivity and falling interest rates; returns for the next 30 years are likely to face the headwinds of a rising rate environment, limited productivity and economic growth, and the consequences of corporate mal-investment after the GFC.

- As if the above factors weren’t enough to drive lower future returns, the current uncertainties across the entire economic (practical and theoretical), technological and geopolitical spectrum are unusual in terms of number, scale and insolubility. Marks notes that most investors are conscious of the music stopping, but can’t think of what negative catalyst might cause the music to stop.

It is against this backdrop that investors must ask if passive investing is the panacea to the poor returns of active investing since the central banks unleashed global quantitative easing. It is easy to view passive investing as a perpetual motion machine: passive has outperformed active over the last decade, so investors shift their assets from active to passive; as more assets flow into passive strategies, index constituents will always find a bid, and thus benchmark indices should keep going up; as benchmarks go up, active managers that don’t want to underperform start gravitating towards index-hugging strategies, but with higher fees; assets continue to flow into passive strategies, either from underperforming active managers, or because investors don’t want to pay active management fees for quasi-index returns. This virtuous cycle continues, underpinning the upward trajectory of the market and consistent returns for the passive investors.

However, time will likely prove this perpetual motion to be rotational for two key reasons. Firstly, passive investing is based on the premise that assets are fairly priced, and thus valuation is useless. Because passive investors don’t consider the relationship between price and value, they don’t contribute to price discovery. A passive strategy is just as likely to buy a rules-based amount of Apple shares at $10 as it is at $1,000. In fact, market cap weighted strategies will buy more of Apple the more overpriced it is. This means that every incremental passive dollar invested makes the market less efficient, which leads to the second reason: the efforts of active investors are required for the market to regain its efficiency. But what happens when more and more active investors lose their jobs to passive strategies? Less participation in the market by active investors means prices will diverge further and further from valuations.

Given today’s equity prices are high and future returns likely to be the lowest they’ve ever been, are investors really adequately compensated for adopting a passive strategy? At the cost of outperformance, the passive investor is guaranteed not to underperform the index1; but this is irrelevant if the risk adjusted return of indexing is inadequate in the first place.

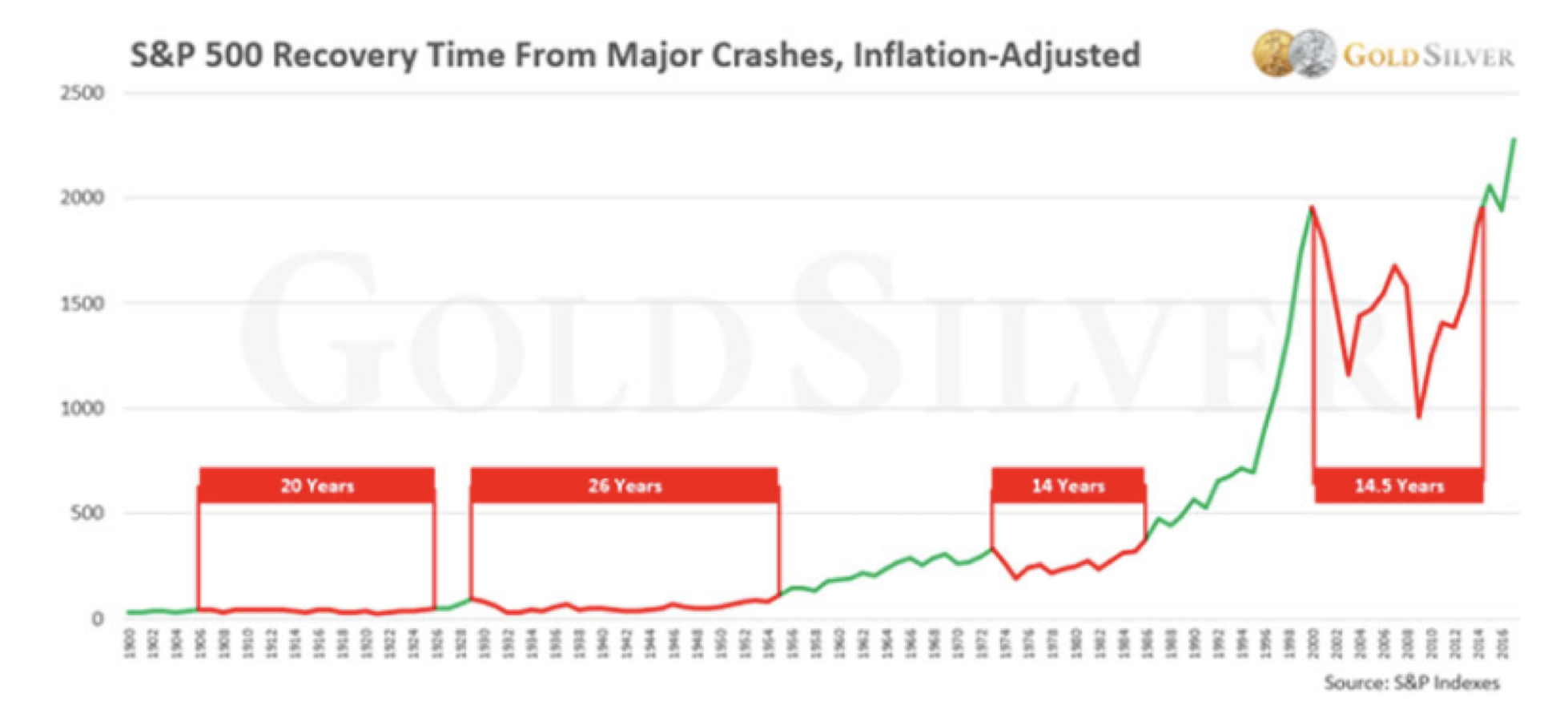

Consider the graph below: it took almost 15 years for a passive investor holding the S&P 500 in 2000 to make back the money they lost in the intervening period, yet the average return of the market in the 30 years to 2014 was still 8%. How many investors could have held on for 15 years and not be scared out of the market by both the dotcom crash and the GFC?

The problem investors face with using average historical market returns to justify a passive strategy is that the averaging period tends to be too long or too short so as to render averages practically meaningless. If, for example, the prospective return over the next 20 years from today’s record high starting point is 6.5%, the typical passive investor imagines their $1,000 investment growing by 6.5% every year to over $3,500 by 2037. However, a 6.5% average return doesn’t mean it’s smooth sailing for two decades. If the first-year return happens to be a 50% decline (as the S&P 500 experienced during the GFC), it would take 8 years for the investor to recover their principal assuming equal annual returns after the first year. If, on the other hand, the investor could mitigate half the decline in the first year (for example, through an active strategy with 50% market exposure and superior stock selection), they would see their investment quintuple to nearly $5,300 after 20 years.

What this suggests to your author is that, with inflated prices and prospective returns that are likely to be much lower than past returns, passive investing may not prove to be the best avenue for building wealth going forward. As we have written about in the past, each unit of outperformance in a low-return and increasingly passive world is proportionately more valuable to investors. Since inception2 to June 30, our Montaka strategy has delivered 17.8% cumulative return, net of fees, compared to 14.1% for the MSCI World Net Total Return Index in Australian dollars over the same period. This has also been achieved with an average of only 48% net market exposure. By going passive, investors are giving up both downside protection and the chance of outperformance at a time when all indicators suggest that capital preservation and the incremental unit of alpha will be most important.

*****

1 Theoretically. In practice, many passive investors underperform their benchmarks due to the human brain’s bias towards extrapolating and chasing returns, which leads to such wealth-destructive actions as buying high and selling low. Legendary fund manager Peter Lynch generated annual returns of 29% over the 13 years he managed the Fidelity Magellan fund. His investors were found to have participated in less than a third of those returns thanks to their tendency to redeem after a period of underperformance, and reinvest after a period of strong outperformance. The very definition of buying high and selling low.

2 1 July 2015.

![]() Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montgomery Global Investment Management. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.

Daniel Wu is a Research Analyst with Montgomery Global Investment Management. To learn more about Montaka, please call +612 7202 0100.